A week of political unrest has laid bare the depth of Nepal’s frustration with the unchanging and uncaring ways of its government. The country’s Gen Z-led nationwide protests erupted after the government banned major social media platforms in a bid to silence criticism of the lavish lifestyles of political “nepo kids.” Within 48 hours, violence spread across Kathmandu. Ministers were attacked, government buildings torched, and 72 people killed as security forces opened fire. Prime Minister KP Oli

resigned soon after and is reportedly seeking exile.

For many, the scenes felt familiar. Nepal’s turmoil mirrors Bangladesh’s youth-led revolt last year that forced then-Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina to resign and flee the country, and Sri Lanka’s 2022 uprising that drove then-President Gotabaya Rajapaksa into exile.

"I think the biggest achievement of this is the signals they have sent to the political parties that you have to fear the people. If you don't deliver, you'll be made accountable. People are not going to remain silent," Pramod Jaiswal, Research Director at Kathmandu-based think tank Nepal Institute for International Cooperation and Engagement (NIICE), said.

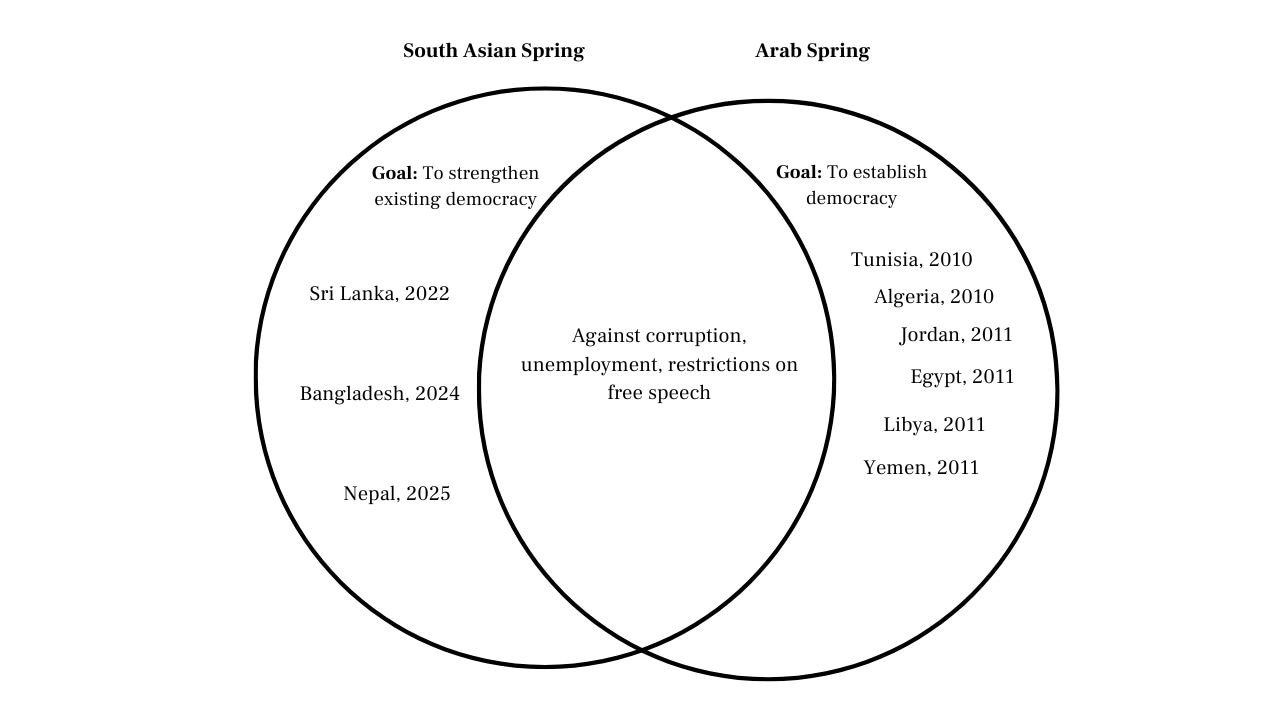

Others say the pattern resembles a South Asian Spring movement.

In all three countries, the youth, worn down by decades of unfair governance, rampant corruption, and lack of opportunities, drove movements that brought down the governments.

“I would go ahead and call it something of a South Asian Spring where the objective is not purely to establish democracy but…to shape the political culture and renounce the democracy and the political institutions that have been in place for a long, long time,” said Aditya Gowdara Shivamurthy, Associate Fellow, Neighborhood Studies at Observer Research Foundation.

Like the Arab Spring movement, tight control on freedom of speech and joblessness are at the centre of the protests in South Asia. Reels that were going viral in Nepal before the government sought to control social media captured people’s resentment about the lack of employment opportunities.

One video shows “nepo kids” dancing in their luxury homes and other Nepalis labouring outside the country to make ends meet. The message reads: “While you flaunt your corrupt wealth without shame, never forget who pays the price with blood, tears, and taxes.”

“The governments have uniformly focused on securing political power and failed to meet the youth’s demands for job opportunities and a good standard of living. Neither of these governments have been able to educate or prepare them (the people) for private sector expansion,” Shivamurthy told CNBC-TV18.

“Fueled by social media, the youth across South Asia has moved rapidly from apathy to anger: it is now engaged and emotional about politics, seeking immediate action. This puts the onus on the leadership to deliver — beyond narratives and promises — tangible economic outcomes in the form of employment and more governance accountability,” said Constantino Xavier, Senior Fellow, Foreign Policy and Security Studies, Centre for Social and Economic Progress (CSEP). “I don't see the future youth of South Asia putting up with an alliance of geriatric leadership and kleptocratic elites.”

Shivamurthy explained that if the Arab Spring began to establish democracy or political rights, the South Asian spring aimed at broader political and cultural reforms to bring structural changes to existing political culture and systems.

Also Read: Young activists who toppled Nepal's government now picking new leaders

People’s champions turned autocratic

A demonstrator poses for photographs where President Gotabaya Rajapaksa used to hold main events at the President's house on the following day after demonstrators entered the building, after President Gotabaya Rajapaksa fled, amid the country's economic crisis, in Colombo, Sri Lanka, July 10, 2022. REUTERS/Dinuka Liyanawatte

Leaders in all three countries came to power as a breath of fresh air for people tired of political instability and civil war.

In Sri Lanka, Mahinda Rajapaksa entered the political scene as a simple man from the rural south in 2005. He remained in office for two terms until 2015, dogged by allegations of corruption. But it was under his brother Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s presidency from 2019 that public anger boiled over. Reckless borrowing pushed Sri Lanka into a crippling debt trap, and the economy collapsed further when the pandemic choked off tourism and remittances. Daily life grew unbearable: citizens endured power cuts of up to 13 hours and queued for hours to buy overpriced fuel and cooking gas. The hardship ultimately ignited mass protests that toppled the government.

In a somewhat similar fashion, Sheikh Hasina was already a heroic figure. The assassination of her family aside, Hasina herself was seen as a pro-democracy icon for leading street protests during the military rule of General Hussain Muhammed Ershad. In 1996, she held office as the country’s prime minister. Although credited with nurturing economic growth in the last few years, Hasina also drew criticism for abusing her power to crack down on freedom of speech and carrying out extrajudicial killings, among other things.

The pandemic and Ukraine war exposed vulnerabilities in the economy that quickly trickled down to the lives of ordinary citizens. According to Chatham House, the readymade garment industry alone accounted for 83% of Bangladesh’s income from exports that suffered from the slightest changes in the global economy. In 2023-24, the country recorded the highest inflation rate (9.73%) since 2011-12. Add to this the government’s decision to impose a quota reserving a 30% chunk of government jobs for Bangladesh Liberation War veterans, which then triggered a wave of protests that toppled the government.

At the same time, the people of Nepal were dealing with political instability for decades since the monarchy was abolished in 2008. The country saw 14 governments change hands in 17 years since then. KP Oli Sharma returned as Prime Minister for the fourth time last year, promising that it would revive hope in people only to walk down the same paths as Sri Lanka and Bangladesh. The Gen Z protest, which led to several killings, is one of the most tragic events in Nepal’s history.

The difference, Shivamurthy said, when compared with the Arab Spring movement, is the shooting and violence seen in South Asia.

A China link

Experts say each unrest is entirely a domestic problem. No external powers have driven citizens to revolt.

However, analysts highlighted that all three South Asian countries and their ties with China and India could have an “indirect relation,” especially as the two Asian giants have vested interests in expanding their influence in the continent.

For China, the infamous Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is a key vehicle to achieve this. China has been accused of using the infrastructure project as a front to further what critics call ‘debt trap diplomacy,’ where China funds ambitious projects in economically weaker countries and gains political leverage when these countries are not able to repay the amount.

Sri Lanka’s Hambantota port is seen as the poster child for the debt trap strategy. The port was built with loans from Exim Bank of China with the promise of turning it into a global shipping hub. However, this plunged Sri Lanka into a debt crisis, and it was forced to lease the port to China for 99 years in 2017. The country owes $4 billion to the Chinese state-owned bank as of June 2024.

Nepal’s airport was also built with a $215.96 million loan for 20 years from Exim Bank and has several ongoing infrastructure projects.

An analysis of 10 years of BRI projects revealed corruption was rampant in most BRI projects in both China and the countries in which it initiated the projects.

“At the end of the day, the question is where did all the money go? Or why didn't these investments bring up a lot of job opportunities? That brings us to the fact that China offers assistance and loans saying they don't really care about corruption or mind the domestic politics…I think somewhere it is indirectly related,” Shivamurthy explained.

With Nepal still inching closer to normalcy slowly, Jaiswal explained that the country remains at increased risk of interference. He said, “We know we are very vulnerable to Chinese activity here...When you have a robust system, it would keep foreign power away to a certain extent, if not 100%.”

Right now, to truly experience the spring of political leadership in India, “safe landing” is important.

Also Read: 'Right Balance': India should focus on Nepal's development, engage with new generation, says Shashi Tharoor

/images/ppid_59c68470-image-175794755681970454.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177069103696049438.webp)

/images/ppid_59c68470-image-177069004415381828.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177069364492857258.webp)

/images/ppid_59c68470-image-177069274594727234.webp)

/images/ppid_59c68470-image-17706927033367981.webp)

/images/ppid_59c68470-image-17706926096387229.webp)

/images/ppid_59c68470-image-177069252798378934.webp)

/images/ppid_59c68470-image-17706926650825720.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177069204176387593.webp)