WASHINGTON (AP) — The Justice Department’s investigation into Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell has brought heightened attention to a key drama that will play out at the central bank in the coming months:

Will Powell leave the Fed when his term as chair ends, or will he take the unusual step of remaining a governor?

Powell's term as Fed chair finishes on May 15, but because of the central bank's complex structure, he has a separate term as one of seven members of its governing board that lasts until January 31, 2028. Historically, nearly all Fed chairs have stepped down from the board when they are no longer chair. But Powell could be the first in nearly 50 years to stay on as a governor.

Many Fed-watchers believe that the criminal investigation into Powell's testimony about cost overruns for Fed building renovations was intended to intimidate him out of taking that step. If Powell stays on the board, it would deny the White House a chance to gain a majority, undercutting the Trump administration's efforts to seize greater control over what has for decades been an institution largely insulated from day-to-day politics.

“I find it very difficult to see Powell leaving before midnight on Jan. 31, 2028,” said David Wilcox, a former top economist at the Fed and senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. "This is a mortal threat to the governance structure of the Fed as we’ve known it for 90 years. And I think that Powell does take that threat exceedingly seriously, and therefore will believe that it is his solemn duty to continue to occupy his seat on the board of governors.”

Powell, 72, was appointed as Fed chair by Trump in 2018, and must step down from the position in May because his second four-year term is ending. He has declined several times to comment on his plans beyond that when asked by reporters. A spokesperson declined to comment for this story.

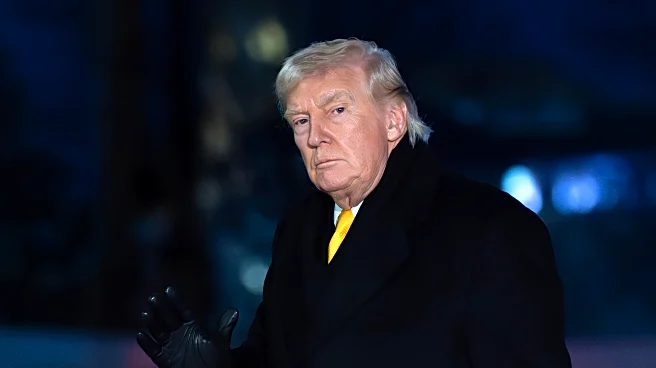

Trump has sought to push out Powell before his time is up, obsessively attacking him for not cutting rates as sharply as the president wants, particularly in light of ongoing concerns about high costs for groceries, utilities, and housing that have remained a salient political issue even as inflation has cooled.

On Tuesday, Trump highlighted that mortgage rates have declined in the past year. “If I had the help of the Fed, it would be easier,” he said. "But that jerk will be gone soon.”

Or maybe not.

Here is a look at the impacts of whether or not Powell stays on the board could have:

Trump said Tuesday that he hopes to name a new Fed chair in the next few weeks. But that could get held up by the criminal investigation of Powell.

Several Republican senators, including at least two on the banking committee who would have to approve Trump’s nominees to the Fed, have expressed skepticism that Powell committed crimes during his testimony last June regarding the Fed’s $2.5 billion renovation of two office buildings, a project that Trump has criticized as excessive. That testimony is the subject of subpoenas sent to the Fed by U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia Jeanine Pirro.

Sen. Thom Tillis, a North Carolina Republican, said he would not vote for any Fed nominees until the legal cloud around Powell is resolved. That would be enough to delay a nomination from getting out of the banking committee.

If no new chair of the Fed's board has been confirmed by May 15, then Powell could remain in that post until a replacement has been confirmed. As a result, the Fed might not cut interest rates anywhere near as quickly as Trump wants.

If Powell stays on as a governor even after he is no longer chair, Trump could still name someone to lead the Fed but that would give him a total of three appointments on the board — including two from his first term — and short of a majority.

So even if Trump nominates a chair who seeks to do the president’s bidding regarding interest rates, that person “would have very little persuasive power with his colleagues," said Wilcox, who is also director of research at Bloomberg Economics. Powell, along with other members of the Fed's 19-member interest-rate setting committee, could outvote the new chair. That hasn't happened since 1986.

In that case, Trump could nominate a fourth person to the board and gain a majority. He could even then add a fifth, if the Supreme Court allows his attempt to fire Governor Lisa Cook to proceed. The high court will hear her case on Wednesday.

A majority on the board would enable the White House to make sweeping changes to the Fed. Trump's Treasury Secretary, Scott Bessent, has advocated numerous reforms to reduce the central bank's influence in the economy and financial markets.

Trump's majority on the Fed's board could also remove some of the presidents of the 12 regional banks, who are members of the Fed's rate-setting committee. The New York Fed president has a vote on the committee and four others vote on a rotating basis.

Several of those bank presidents have expressed opposition to the deep rate cuts that Trump has demanded. The board of governors could seek to have them fired if a chair wanted to do so.

While nearly all Fed chairs have left the board of governors before their terms were up, there is some precedent for Powell to stay. In 1978, then-Chair Arthur Burns stayed on the board for about three weeks after his chairmanship ended. But in 1948, then-Fed chairman Marriner Eccles remained as a governor for three years after finishing as chair, in part because President Harry Truman asked him to remain.

In 1951, however, he played a key role in undercutting the Truman administration in a dispute over interest rates, which led to the Fed-Treasury Accord that established the modern Fed as a largely independent institution.

Eccles became a symbol of Fed independence, though some academics say that reputation is overstated. The Fed's principal office building —- currently under renovation and at the center of the criminal investigation of Powell — is named after him.

Truman then appointed a Treasury official, William McChesney Martin, to the Fed chairmanship and assumed he would do his bidding. Yet Martin defied Truman and raised interest rates. Years later, Truman ran into Martin in New York City and called him a “traitor.” The Fed's second office building in Washington is named after Martin.

“So it's a cautionary tale also for Trump, thinking he's going to get his own Fed chair in there,” said Lev Menand, a law professor at Columbia University who studies the Fed. “Martin didn't do what Truman wanted.”