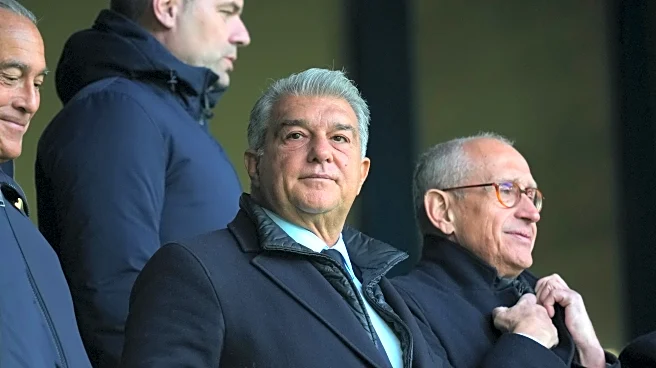

MANILA, Philippines (AP) — Juan Ponce Enrile, the Philippine defense chief during a martial-law era notorious for human rights atrocities, democratic setbacks and plunder who later broke off from then dictator Ferdinand Marcos in a schism that eventually led to the latter’s overthrow in a 1986 “people power” uprising, died on Thursday. He was 101.

Katrina Ponce Enrile said her father died at home surrounded by family as he had wished, but did not immediately

provide other details. She said her father had been confined in a medical intensive care unit for pneumonia treatment.

President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., the incumbent Philippine leader and son and namesake of the authoritarian ruler Enrile helped overthrow, praised Enrile and said his death “marks the close of a chapter in our nation’s history.”

“We say goodbye to one of the most enduring and respected public servants our country has ever known,” Marcos said in a statement. “For over 50 years, Juan Ponce Enrile dedicated his life to serving the Filipino people, helping guide the country through some of its most challenging and defining moments.”

One of the country's most prominent lawyers, Enrile was also one of the longest-serving officials in Philippine history with a career in government that spanned for more than a half century. He had served in various posts under the elder Marcos starting when the latter won the presidency in 1965. in 2022, the current president appointed Enrile as chief presidential legal counsel, at age 98.

Among the departments Enrile led were justice and finance, including a stint as Bureau of Customs commissioner. He served three terms in the Senate, where he became president from 2008 to 2013. He was a former member of the House of Representatives to represent the northern province of Cagayan, where he was born on Feb. 14, 1924.

In 2014, Enrile surrendered after he was indicted and ordered arrested by an anti-graft court for allegedly receiving huge kickbacks from a scam that diverted millions of dollars from anti-poverty and development funds allotted to lawmakers. He denied the accusation and enlisted top-notch lawyers to defend him.

After a year of detention, the Supreme Court granted Enrile’s petition for bail in 2015 for humanitarian reasons. He was cleared of graft charges just last month after a lengthy trial.

His most controversial role, however, was as head of the Department of National Defense, where he was reappointed in 1972, the year the elder Marcos placed the entire Philippines under martial rule purportedly to defend the country from increasingly violent left-wing demonstrations in the capital Manila and growing threats from Marxist guerillas in the countryside and Muslim separatist insurgents in the south, homeland of the minority Muslims in the largely Roman Catholic nation.

Opponents, however, accused Marcos then of declaring martial rule, a year before his term was to expire, to prolong his grip on power amid growing discontent over his rule and allegations of massive corruption and cronyism. Marcos padlocked Congress and newspaper offices, ordered the arrest of political opponents and activists and ruled by decree. Thousands of Filipinos were incarcerated, tortured and disappeared. Some have never been found to this day.

A growing rift between Enrile and Marcos and his loyalist generals prompted the defense chief to break away from the ailing president after a coup attempt staged by Enrile-aligned military officers was discovered and failed. Fidel Ramos, then a top official of the Philippine Constabulary, also withdrew his support from Marcos. Ramos became president in 1992 and died in 2022.

Millions of Filipinos converged in February 1986 at the EDSA highway to shield Enrile and Ramos from Marcos’ loyal forces. Marcos was driven with his family and cronies into U.S. exile.

The 1986 “people power” uprising became a harbinger of change in authoritarian regimes. Decades since then, however, poverty, stark inequality between the rich and poor and a failure to address past wrongdoings have remained deeply entrenched, fanning political and social divisions.

In the tumultuous post-dictatorship era, Enrile was detained twice after being linked to several military rebellions, including mutinies against President Corazon Aquino, the pro-democracy leader who succeeded Marcos.

The Department of National Defense, where Enrile had been the longest-serving chief, paid tribute to him on Thursday, flying the Philippine flag at half-staff.

“His long and storied career in public service marked profound changes in our nation’s history,” the defense department said in a statement. “His legacy in our country’s politics and governance will always be remembered.”