SANTIAGO, Chile (AP) — Fans sported MAGA-style caps. AC/DC blasted from the speakers. Red, white and blue flags flapped in the wind. Crowds whooped and cheered as the man of the hour lamented the surge

of migrants across the border.

“This country isn’t falling apart,” he bellowed. “It is being shot to pieces, by bullets.”

You’d be forgiven for assuming this was a rally for U.S. President Donald Trump. After all, the U.S. president's name adorned plenty of campaign merch.

But this eruption of visceral rage at immigrants and incumbents took place in Santiago, Chile, at the final campaign event for Johannes Kaiser, a radical libertarian candidate gaining traction before Sunday's presidential election in Chile, where rising fears of uncontrolled migration have pushed everyone in this race — even the governing coalition's Communist candidate, Jeannette Jara — to the right.

Kaiser is “the only one with a firm hand, the only one who can pull us out of the United Nations, close the borders to all the Venezuelan criminals and throw them in prison in El Salvador,” said Claudia Belmonte, 50, peering out from beneath the brim of a red baseball cap emblazoned with Kaiser’s promise to “Make Chile Great Again.”

Such demands for a “mano dura," a “firm hand,” against crime and disorder have reshaped Chilean politics as transnational gangs like Tren de Aragua surged across porous borders from crisis-stricken Venezuela and elsewhere in recent years, importing kidnappings, contract killings and other violent crimes previously unseen in one of Latin America's safest nations.

“People in Chile never had problems with foreigners. But you hear about a gang burying someone alive in your neighborhood and it changes you,” said Carlos Jadué, 49, a lemon vendor in central Santiago. “I'm not racist. I see new people coming in. And I see new crimes.”

The anti-migrant backlash has transformed a nation that just four years ago elected the bright young hope of the Latin American left, President Gabriel Boric, a millennial former protest leader who handily defeated the ultraconservative lawyer José Antonio Kast in 2021 with vows to “bury neoliberalism" in response to demands of the nation's 2019 social upheaval.

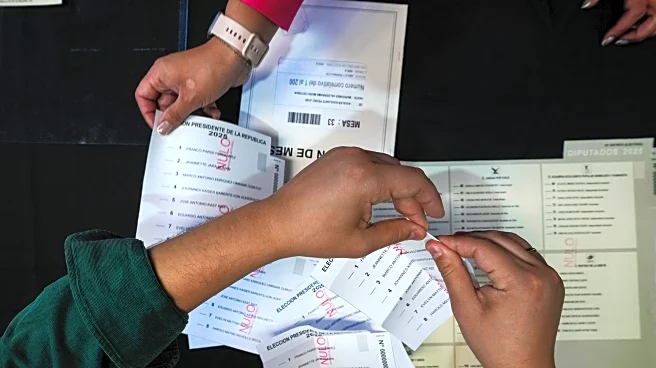

This time around, experts say Chile's nativist fears over illegal immigration give Kast a better shot, even if he's unlikely to clinch the 50% of votes needed to win outright in Sunday’s first round. Polls show Kast facing off against Jara in a runoff on Dec. 14.

In Santiago, there are few vestiges left of the 2019 mass protests against endemic social inequities — known here as “el estallido” or “the explosion" — in which as many as a million Chileans marched to vent a generation’s worth of economic and political grievances.

One is the stone plinth in the city's Plaza Italia, the central square where protesters battled nightly with police, torching buildings and braving bird shot. The bronze statue of 19th-century Chilean war hero Gen. Manuel Baquedano was defaced, then taken down for what authorities promised would be a quick restoration.

Four years later, the stone plinth, scarred by anti-government graffiti, remains empty and freighted with symbolism. For protesters, it's a reminder of all that's unaddressed. Neoliberalism is alive and well. Chile retains the 1980 constitution adopted by military dictator Gen. Augusto Pinochet after Boric twice failed to change it.

For critics, it's a reminder of the lawlessness that struck Chile, a stable prosperous nation that long distinguished itself from its more volatile neighbors. Many Chileans trace their feelings of insecurity back to those days of civil strife, when everything they knew about their country burst.

“I was left-wing until the ‘estadillo,' when I watched chaos taking over our streets,” said Sebastian Jaramillo, a 36-year-old graphic designer at Kaiser’s rally on Wednesday. “I started watching YouTube videos about the decline of our country, I got politicized.”

In the riled-up rallies of Kaiser and Kast, some recognize a familiar revulsion at the centrist consensus that has held sway since the dictatorship.

“The anger from the ‘estallido’ didn’t disappear. It stayed, it festered,” said Juan Medina, 40, who works at a theater in downtown Santiago. “Instead of turning our anger on inequality, the economic system, the political class, we’ve redirected it toward migrants.”

Throughout the campaign, Chile’s presidential contenders have seemed most intent on trying to outdo each other with ruthless anti-immigrant proposals inspired by Trump and El Salvador’s iron-fisted president, Nayib Bukele.

It's not only on the right.

Jara of the Communist Party — the only left-wing front-runner, as Boric can't run for a consecutive term — has also leaned heavily into a law-and-order message, promising to build new prisons and deploy more force to Chile’s borders.

Jara advocates raising the minimum wage, but, in stark contrast to Boric, proposes no changes to Chile's market-led economic model. The former labor minister and union leader dropped plans to nationalize lithium and copper mining. Her platform calls insecurity her “top priority.”

“Observers say this is an election between two extremes — a communist candidate, two far-right candidates,” said Robert Funk, a political scientist at the University of Chile. “But actually, there’s quite a lot of consensus on things like immigration.”

Kast, a devout Catholic and father of nine who opposes same-sex marriage and abortion, even in cases of rape, has kept quiet about his conservative values this time around.

His German-born father’s Nazi party membership has hardly come up. After two failed presidential bids, Kast has found his tough-on-migration platform holds more appeal than his culture war battles. Yet for all his vows to deport tens of thousands of people and build a giant border wall, Kast looks moderate next to Kaiser.

Kast and Kaiser “are going to clean Chile up, so it can be a first-world country,” said Alatina Velázquez, 20, a fashion design student who said she lost two close friends in the last two years to gang violence.