Community members first noticed the Border Patrol cars in early January.

Though Froid — a tiny town in northeast Montana — is just 50 miles from the U.S.-Canada border, Border Patrol cars are not a common sight outside of the occasional gas station stop. About two weeks ago, however, residents told Montana Free Press that the number of Border Patrol vehicles increased. Two cars were stationed outside a local auto repair shop and one near the shop owner’s

house, they said.

It didn’t take long for word to spread in the small community of about 195 people that the federal immigration agents were watching 42-year-old Roberto Orozco-Ramirez. The father of four, who is technically a citizen of Mexico, has lived in Froid with his family for more than a decade, long enough that the local auto repair shop, Orozco Diesel, bears his name.

Orozco-Ramirez, his wife and their four sons are fixtures in the small community. His sons are active in school sports, and Orozco-Ramirez coached baseball Little League teams in his spare time. He built an auto shop where community members say he went above and beyond for customers. Though Orozco-Ramirez worked long hours, Froid residents say, he made time for school and community events, often showing up in his work clothes.

As of this week — following a sequence of events that is forcing a deeply red town to confront their own complicated beliefs on immigration — it’s unclear if he will be in the United States much longer.

On Sunday, Border Patrol arrested Orozco-Ramirez and he was transported to Roosevelt County Jail, about 67 miles from his house. The U.S. government charged him with illegal reentry into the country and threatening a federal officer, criminal charges that could ultimately result in hundreds of thousands of dollars in fines, imprisonment or deportation. On Wednesday afternoon, he appeared in federal court in Great Falls. A U.S. Department of Justice lawyer wearing a black suit advocated for Orozco-Ramirez to remain in detention, calling him “dangerous.” Several of the dozen or so Froid residents, who had driven seven hours to show their support for their neighbor, shook their heads.

A public defender rebutted this, referencing a previous statement by the local sheriff stating he “posed no danger to the community.” Court documents say Orozco-Ramirez has no criminal history.

Ultimately, federal Judge John Johnston set a preliminary hearing, where a judge will determine if there is enough evidence for the case to proceed, for Feb. 5 and a detention hearing, to determine whether he should be released on bail throughout his case, on Feb. 9. He will remain in detention until then.

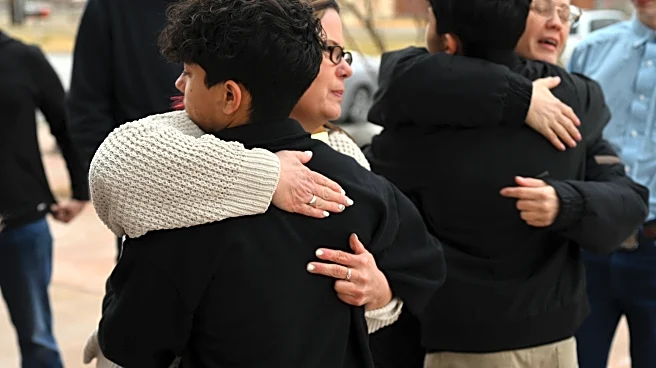

Exiting the courtroom after the hearing, Orozco-Ramirez’s son, Roberto Orozco Lazcano, 18, hugged his two younger brothers. Neighbors embraced, wiping tears from their eyes. “It’s nonsense,” Brittney Nordlund, who works in Froid Public Schools, said of the allegation that Orozco-Ramirez is “dangerous.”

“They’re lying,” Rachel Sundheim, another Froid resident, said through tears. “He is the role model we want in our community.”

Their decision to travel nearly 400 miles — one way — to the hearing, which lasted all of eight minutes, was just the latest of many community efforts to show their support for their neighbor. Though the vast majority of Orozco-Ramirez’s neighbors voted for President Donald Trump, who has made vows to deport “illegal aliens” a centerpiece of his administration, the town has rallied to support him — since his arrest they have demonstrated their outrage at Border Patrol through protests, letters to lawmakers, public Facebook posts and now their presence in the courtroom.

“The community responded more than I ever thought,” said Orozco Lazcano, a freshman at Williston State College in North Dakota, who returned to Froid last week when his dad called and said Border Patrol was staged outside his business. “They’re giving us help I didn’t know we needed.”

Most people in Froid work in agriculture, producing wheat, alfalfa and barley and raising cattle. Others work in the school, post office, bank, or oil fields. Liz Melbourne, who graduated from Froid Public Schools and whose kids now attend school there described the 0.6 square mile town as a “storybook” community and called the recent incident with Orozco-Ramirez — one of just 11 or so Hispanic residents according to Census data — “eye-opening.”

“I think it pretty much rocked everybody’s world to see something like this,” said Melbourne. On Sunday, just before she learned that Border Patrol agents had taken Orozco-Ramirez away, Melbourne stood for five hours with a handful of protesters on the side of the road near Orozco-Ramirez’s business.

Roberto Orozco-Ramirez, a business owner in Froid, Montana, stands with his four children. Credit: Provided by Laura Christoffersen

Melbourne, who doesn’t describe herself as Republican or Democrat, said she understood Trump’s immigration policy to be about arresting and deporting people who were living in the U.S. illegally and who had also committed crimes. That’s one reason why Orozco-Ramirez’s detainment came as a shock.

“They weren’t criminals,” she said. “Roberto is a father, he opened his own business. He has a great family. They’re just model citizens.”

The other shock, for Melbourne and her neighbors, was that Trump’s national immigration crackdown had extended beyond big cities, like Chicago and Minneapolis, and infiltrated her small town.

“That’s my fear,” she said. “It’s that I’m living in a small town and now this is in my backyard.”

To resident Laurie Young, Orozco-Ramirez and his family embodied the American dream.

“When they moved here, they never asked for anything,” she told MTFP in an interview Monday, choking back tears. “They bought a home, put their kids in school, they built that business from the ground up. They just worked their butts off. … When I think of people coming to the U.S. for a better life, I just can’t imagine any family doing more than he has.”

Orozco-Ramirez’s diesel shop in Froid provided crucial services to community members who would otherwise have to drive an hour to Williston, North Dakota, for repairs. Keith Nordlund, a technician at a local power plant who attended the hearing with his wife Brittney, said Orozco-Ramirez once worked through the night, and in cold winter temperatures, to repair a school bus that had lost heat.

“He did it for the school,” Nordlund said. “He did it for the kids to ensure they’d have a safe ride. He’s always looking out for everybody else. He’s doing what he can to help anybody and everybody.”

Nordlund, who’s been in touch with Orozco-Ramirez’s family, said it was obvious that Border Patrol was targeting them over the past month. Orozco-Ramirez’s children, who range in age from second grade to college, told him they couldn’t leave their house without being pulled over.

“Anytime they took off driving, Border Patrol would wait until they’re a ways away, pull them over, check the vehicle, make sure there was nobody else inside of it and then just send them on their way,” he said, adding that Orozco-Ramirez’s children were born in the U.S. and are American citizens. “They would follow them to and from school. It got so bad, all of the kids are no longer in school.”

In a school of 81 students from pre-kindergarten to 12th grade, Young said, those absences felt “loud.”

Young, another community confirmed, at the hearing, that Border Patrol was often parked one block from school. “We have three streets in town. There was no avoiding them!” she said

“The kids don’t know what to do for their friends,” she said, adding that her son is friends with Orozco-Ramirez’s son. “And it’s so hard to explain to them. How do you explain that this is the culture of our country right now? There’s no good way.” Representatives for Border Patrol did not respond to a request for comment on how they interacted with Orozco-Ramirez’s children.

According to court filings, in March and July, two of Orozco-Ramirez’s brothers were apprehended by Border Patrol in Scobey and Bainville, two other small towns in northeast Montana. Orozco-Ramirez was then identified by Border Patrol agents in the area who believed he was in the U.S. illegally. The complaint alleges that Orozco-Ramirez “was removed” from the U.S. in 2009 by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

On Jan. 15, wearing plain clothes and driving in unmarked vehicles, according to the complaint, Border Patrol agents knocked on the door of Orozco Diesel. Orozco-Ramirez was suspicious of the officers and refused to let them into the building, according to court documents. Border patrol agents also accuse him of yelling threats at them as they left the area and throwing a two-by-six piece of lumber in their direction as they drove away.

Laurie Young, a Froid resident, was not present at the time of the arrest, but she was sympathetic of a desire to throw something and yell at plain-clothed agents driving in unmarked vehicles.“They tried to force their way in. Came back with rifles. If anyone showed up to our door in regular clothes, I would do the same thing,” she said.

On Sunday, the Roosevelt County Sheriff’s Office announced in a Facebook post that a man, later confirmed to be Orozco-Ramirez, had surrendered to local law enforcement after Border Patrol agents were staged near a business in Froid.

“It’s important to note that the man and his family have been productive members of the community and have had no negative interactions with local law enforcement since they moved here over a decade ago,” the Facebook post reads. “The man posed no danger to the community at any point during this incident.”

The complaint states that there is no record within the Department of Homeland Security that he applied for permission to re-enter the United States after he was removed from the U.S. by ICE in 2009. The complaint also states Orozco-Ramirez “was identified as a Surenos gang member when initially encountered in Logan, Utah.” Representatives for Border Patrol did not respond to questions about how the agency made that determination or what allegedly happened in Utah. Border Patrol made dubious gang affiliation claims in at least three other cases in Montana in 2025.

Alex Rate, legal director of ACLU Montana, said that references to gang affiliation can lack credibility.

“We have seen that this administration has trumped up allegations of criminal behavior or gang participation in order to justify the detention and removal of an individual who otherwise had no gang affiliation or criminal history,” he said. “It’s been weaponized in a way that’s particularly harmful to immigrants and immigrant communities.” Border Patrol made similar gang allegations in three other Montana cases in 2025 that defense attorneys disputed and judges later dismissed.

Froid residents said they were stunned by the gang accusation.

“That may work in a big city where people don’t know each other,” Young said. “That won’t work here.”

The penalty for illegal re-entry in the U.S. is up to two years imprisonment and a $250,000 fine, and the penalty for threatening a federal officer is up to six years imprisonment with a $250,000 fine. Either conviction could lead to deportation.

Just before Orozco-Ramirez was detained Sunday, a handful of Froid community members stood on the side of the road near Orozco Diesel holding signs in support of his family. Passersby honked and waved in support. One flashed a middle finger, according to Melbourne, who attended the protest.

And hours after the Roosevelt County Sheriff’s Facebook post went up that evening, Froid residents began circulating a digital flyer, showing photos of Orozco-Ramirez and his family, reading “STAND WITH THE OROZCO’S” in big, block letters. Others encouraged people to write and call members of Montana’s delegation expressing concern. Some people, Nordlund said, collected donations to cover Orozco-Ramirez’s legal fees; others organized a meal train for his family. Young asked people to share personal statements and photos showing Orozco-Ramirez’s community involvement, should they be helpful to the family in court.

A sample email template addressing Montana elected officials that’s circulating among Froid residents describes Orozco-Ramirez as “a respected and deeply rooted member of the community” and encourages Montana lawmakers to review his case. It also asks leaders for guidance “in determining whether any lawful pathways may exist that could allow Mr. Orozco Ramirez to pursue legal status.” Nordlund, whose son is friends with Orozco-Ramirez’s son, said he sent the email to Gov. Greg Gianforte and Sens. Steve Daines and Tim Sheehy.

Attending the hearing on Wednesday was the next logical step. Some neighbors carpooled in large SUVs. Orozco-Ramirez’s sons drove together, leaving their terrified mother and second-grade brother back in Froid. Some neighbors carpooled in large SUVs. Orozco-Ramirez’s sons drove together, leaving their terrified mother and second-grade brother back in Froid. Kate Eby, a nurse in Great Falls,who had never met Orozco-Ramirez was amongst their midst. She said she heard about the hearing in Great Falls from a coworker who lived in Froid. She made sure to attend and show her support.

“It’s easy to look at Minneapolis and say it’s far away, and that doesn’t happen here,” she said. “But it does. And it’s not the same. Compared to big cities, we’re lacking resources. We’re lacking numbers. But to have community in Montana, the boundaries have to be a little bit bigger. I wanted the family to know we’re here.”

When people are taken by law enforcement, transferred to facilities and deported, she said, it’s hard to know where they end up.

“Paying attention like this keeps people safe,” she said.

Nordlund, who expressed his support for Orozco-Ramirez on Facebook, said he’s mostly heard from people who want to help but has also received some criticism.

“They said, ‘I can’t believe you’re helping them. I can’t believe you’re doing this,’” he told MTFP. “I said, ‘You know what? Up until six months ago, I didn’t know Roberto was illegal. And he is my friend. His status doesn’t change that I am his friend.’ Do I agree with him being here illegally? No, I actually don’t. But all I can try to do is help him become legal.”

___

This story was originally published by Montana Free Press and distributed through a partnership with The Associated Press.