LOS ARRECIFES, Mexico (AP) — The sun has set and the clouds are washed in purple as Mauricio Contreras and his daughter Eunices head out to fish in the Gulf of Mexico. Eunices casts the heavy net for snapper,

pollock or cabrilla while her father pilots their small boat.

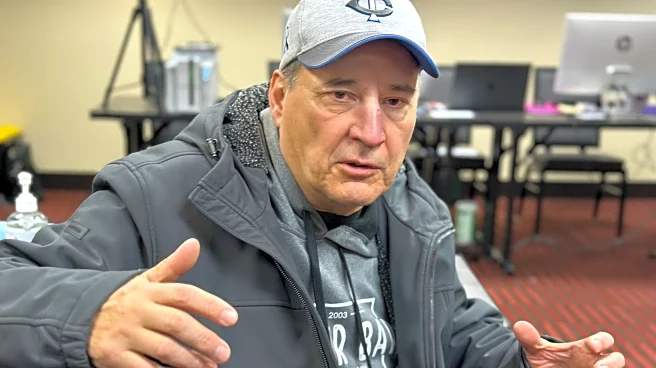

Contreras, an anchor dangling from a silver chain against his deeply tanned skin, has been doing this for more than 40 years. But he worries the family's main source of income is now at risk from an underwater pipeline completed last year to import natural gas from the United States.

“When they started laying it, it affected us because the boats were dropping explosives and you could hear it all the way here, right on the shore,” Contreras recalls. Now that it's operational, he worries about leaks: “It’s a constant danger that will always be there, and it’s a risk for the entire fishing industry.”

The pipeline known as Southeast Gateway was built by Canadian company TC Energy in partnership with Mexico’s state-owned power company CFE. It adds 700 kilometers (435 miles) to a line that now stretches from southern Texas to Tabasco state, where it's supplying electricity for a major oil refinery. But its main goal is to someday deliver gas to the Yucatan Peninsula when the expansion of another pipeline is completed.

Southeast Gateway is part of a wave of projects that would allow Mexico, already the world's single largest buyer of U.S. gas, to bring in even more for its own use and to re-export to Asia and Europe. But that faces growing resistance from communities and environmental groups who say the strategy increases use of a polluting fossil fuel, deepens dependence on the U.S. and puts Mexico's climate commitments at risk.

More than 40,000 people across Veracruz make their living from the sea, including Contreras, who lives in a community where fishing is almost the only work. He joined residents of 15 coastal communities last year in a lawsuit over the pipeline that was dismissed, but is under appeal.

They allege that their communities, mostly Nahua and Nuntajiiyi' Indigenous peoples, weren't consulted before construction began as required by Mexico's Constitution.

“We do not agree with this gas pipeline megaproject because we were never informed about it. We were never consulted and therefore we do not know the consequences it will have,” Maribel Cervantes, an activist and teacher who joined the lawsuit, said.

The government argued that Southeast Gateway was a matter of national security and kept some information about it secret, including its exact route. President Claudia Sheinbaum said last year that it was important for natural gas to reach the area.

Greenpeace warned that dredging to bury the pipeline could affect deepwater reefs that are home to many species, some not found in shallow reefs. Pablo Ramírez, Greenpeace Mexico's energy and climate change program coordinator, also said methane leaks could affect ecosystems like the reefs. They sustain important species, including green and olive ridley sea turtles that nest on the beaches of communities such as Los Arrecifes.

In a video last September, TC Energy said experts had “thoroughly analyzed the marine environment to ensure that the route was designed to preserve ecosystems.” The Canadian company declined an interview but said the pipeline created 4,000 jobs during construction and met all federal requirements. It said the project “brings natural gas to the southeast of Mexico for the first time, opening opportunities for economic and social development in one of the poorest regions of the country.”

Mexico's push for U.S. gas dates to a 2013 reform that opened its energy sector to private and foreign investment, said Víctor Ramírez of energy consulting firm P21Energía. The goal was to reduce the use of more polluting fuels, such as fuel oil and coal, and take advantage of low natural gas prices in the U.S.

Now, as the U.S. seeks new markets for gas fracked from the Permian Basin in Texas, Mexico offers not only a strategic geographic position for re-export but also more favorable political conditions for reaching markets the U.S. cannot easily access, said Wilmar Suárez, an energy analyst at Ember.

In turn, Mexico can resell that gas to other countries at a profit, Suárez said.

Southeast Gateway is currently supplying gas only to the $20 billion Dos Bocas refinery, one of former President Andrés Manuel López Obrador's flagship projects and Mexico's largest refinery. But it could eventually carry more than 1.3 billion cubic feet of gas per day if the government's ambitious plans are realized.

Those include completing another pipeline to connect Southeast Gateway with a planned plant in Oaxaca that will convert the gas to liquid for shipment to Asia. These plants burn part of the gas to power liquefaction, generating polluting emissions, said Claudia Campero of the Mexican nonprofit Climate Connections.

Liquefaction plants have drawn the most opposition in recent years. That includes the Saguaro project, a planned 800-kilometer (500-mile) gas pipeline from Texas to the fishing community of Puerto Libertad, in Sonora. There, the U.S. company Mexico Pacific wants to build a plant to liquefy 15 million tons of gas per year for shipment to Asia.

Such shipping would pass through the Gulf of California, threatening whales because it's a key area for reproduction, Campero said.

The project is on hold due to lawsuits.

Mexico’s first export terminal for liquefied natural gas began operating in 2024, but many more are planned. If all of those come online, Mexico would have eight, with most along the Pacific coastline, according to Global Energy Monitor. The U.S. currently has nine.

Both Víctor Ramírez and Suárez said Mexico's natural gas strategy now jeopardizes its energy sovereignty.

More than 60% of Mexico’s electricity comes from gas-fired power plants, and about 70% of that gas comes from the U.S. Fitch Ratings said last year that Mexico's reliance on U.S.-piped gas will continue to grow because of rising demand, insufficient domestic production and the buildout of pipelines.

“It is very easy for the U.S. to impose certain conditions on Mexico because it has a dominant position over gas supplies," Suárez said.

The Ministry of Energy did not respond to interview requests.

Pablo Ramírez, of Greenpeace, said completing all the pipeline projects would make it unlikely Mexico could meet its goal of reducing net carbon dioxide emissions by 31% to 37% by 2035. And Suárez, of Ember, said the strong focus on gas raises doubt about Mexico more than doubling — to 45% — its electricity from renewables by 2030, as promised by Sheinbaum.

Sheinbaum inherited most of the gas projects and must honor those commitments because funds have been invested, said Víctor Ramírez, of P21Energia. But he found optimism in the Ministry of Energy approving 20 private renewable energy projects in December.

Back in Maribel Cervantes' courtyard in San Juan Volador, far from where Mexico City's powerful make energy policy decisions, she demanded that officials take communities like hers into account.

“As Indigenous peoples, we demand that our right to autonomy and self-determination be respected," she said. "We don't want them imposing their megaprojects on us.”

___

De Miguel reported from Mexico City. Data journalist M.K. Wildeman contributed from Hartford, Connecticut.

___

The Associated Press’ climate and environmental coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.