Few figures in India’s wildlife history evoke as much fascination as Jim Corbett, the man known affectionately as ‘Carpet Sahib’ in the Kumaon hills. His

stories, his hunts, his understanding of nature, and his journey from a hunter to a pioneering conservationist have made him a legend whose shadow still lingers in the jungles of Uttarakhand, especially around Corbett National Park, India’s first national park and one of the crown jewels among the national parks of India. For millions of readers worldwide, Man-Eaters of Kumaon and The Man-Eating Leopard of Rudraprayag were their first passport into the forests of India. Corbett’s books are not just adventure tales; they are an evocation of an India with villages, mountain trails, forests, and paths where humans and wildlife intertwine.

Who Was Jim Corbett?

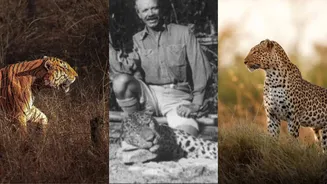

Born in 1875 in Nainital, when British India was firmly in the Victorian era, Edward James Corbett grew up in a world defined by hills, forests and wildlife. His father worked in the British administration, with Corbett spending a large part of his life in Nainital only. Experts often say Corbett “knew the forest like no one else.” His deep understanding of animal movement, forest acoustics and terrain would later make him a uniquely successful tracker of man-eaters.Was Jim Corbett A Hunter?

It is a generally known fact that Corbett killed 33 man-eaters. This includes 19 tigers and 14 leopards. But Corbett never considered himself a trophy hunter. He hunted because local administrations and terrified villagers pleaded for help when a tiger or leopard turned man-eater.For readers of his book, Corbett often feels like a detective. He would get requests, studied it, gathered evidence, interviewed villagers, walked the terrain to piece together the behaviour of the individual animal. With no camera traps or drones but instinct and skill, he identified the exact animal responsible for attacks. His hunts saved countless lives in Kumaon and Garhwal. The Champawat tigress, responsible for over allegedly 200 deaths, remains one of the most chilling man-eater cases in history. He also killed Panar, a leopard who had also reportedly killed over 400 people in India.

Though many British officers wrote about the wild, Corbett was different. His writing had heart, humility and reverence for nature. But as India’s forests shrank and tiger numbers plummeted, Corbett grew increasingly alarmed.

It is said that he never took trophies from man-eaters, as was (and is) the case with trophy hunters. He never charged for his services either. In his book, he wrote, "Tigers, except when wounded or when man-eaters, are on the whole very good-tempered...Occassionally a tiger will object to too close an approach to its cubs or to a kill that it is guarding. The objection invariably takes the form of growling, and if this does not prove effective itis followed by short rushes accompanied by terrifying roars. If these warnings are disregarded, the blame for any injury inflicted rests entirely with the intruder."

Long before conservation became policy, he wrote passionately about the inevitable decline of wildlife unless their habitats were protected. His shift from hunter to protector made him a pathfinder for modern tiger conservation. The later success of Project Tiger, and the continued prominence of Corbett National Park, owe something to the values he planted early.

The Birth of Corbett National Park, A Legacy That Lives On

Established in 1936 as Hailey National Park and later renamed in his honour, Corbett National Park remains India’s oldest national park and a global hotspot for tiger tourism. Corbett hoped the park would help preserve the forests he loved. That wish was fulfilled, as it now stands as one of the most visited and most biodiverse national parks in India. It is the park that keeps his memory alive, but not as a colonial hunter - as a man who helped Indians and the world understand the importance of living with wildlife.In the Man-eaters of Kumaon, Corbett perfectly encapsulated his feelings about tiger conservation. “Tiger is a large-hearted gentleman with boundless courage and that when he is exterminated—as exterminated he will be unless public opinion rallies to his support—India will be the poorer, having lost the finest of her fauna.”

Corbett left India after Independence and settled in Kenya, where he again immersed himself in wildlife, even guarding Queen Elizabeth on her honeymoon. But India never left him. He left his property in India to his tenants too. He died in 1955, and 2025 marked his 150th birth anniversary.

Was he a saint? No. He wasn't a villain either. He was just a product of his time. However, it can't be denied that his writings, empathy and pioneering conservation instincts still remain embedded in how India sees its forests.