In the last two decades, social media has transformed the nature of political mobilisation across the world. Platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp were instrumental in inciting, organising,

and amplifying protests during the Arab Spring. What began as organic expressions of public anger in several West Asian countries soon revealed how quickly digital tools could be used to shape narratives, mobilise crowds, and even accelerate regime change. Since then, similar patterns have appeared in different parts of the world, including South Asia.

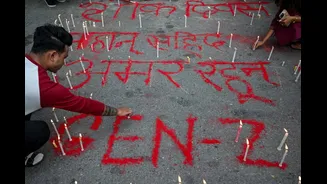

Recent developments in the region raise important questions. Sri Lanka witnessed a dramatic political upheaval driven by public anger over economic collapse, with young protesters playing a visible role. In Bangladesh, student-led movements have historically altered political trajectories, including the toppling of governments. Nepal, too, has seen Gen Z-driven political churn, with youth-led activism contributing to regime changes and prolonged instability. These examples show that young people, when mobilised effectively, can become a decisive political force — for better or worse.

Against this backdrop, the situation in India stands out. India today enjoys relative political stability and remains one of the fastest-growing major economies in the world under the Modi government. Large-scale infrastructure projects, welfare delivery through digital platforms, and consistent electoral mandates have created a sense of continuity in governance. Historically, India’s experience suggests that coalition governments are more vulnerable to external pressure and internal fragmentation, making them easier to destabilise. A strong central government, by contrast, is harder to shake through street-level agitation alone.

This has led to concerns in some quarters that organised efforts may be underway to manufacture instability in India by misleading the youth. India has a massive Gen Z population — digitally connected, socially aware, and emotionally invested in issues such as climate change, pollution, social justice, and employment. While these concerns are genuine, the fear is that they can also be selectively amplified, oversimplified, or weaponised to provoke anger rather than informed engagement.

Interestingly, after the period of violent upheaval in Nepal, the Leader of the Opposition in India made references to Gen Z, drawing attention to this demographic at a time when youth-led movements were generating controversy in the neighbourhood. Such statements, while not inherently problematic, inevitably invite scrutiny over whether political messaging is being calibrated to encourage confrontation rather than constructive participation.

Adding to this perception is the changing tone of certain media voices. Some television anchors and commentators who were broadly supportive of the government over the past decade have suddenly adopted a more provocative approach, urging youth mobilisation on emotionally charged issues such as air pollution and mining in the Aravalli mountain range. These are undoubtedly serious and legitimate concerns, particularly for Gen Z, which is deeply conscious of environmental sustainability. However, critics argue that the framing of these issues often prioritises outrage over nuance, and agitation over policy literacy.

The central question, therefore, is not whether Gen Z should protest — peaceful protest is a democratic right — but whether protests are being shaped or manufactured in ways that prioritise instability over solutions. India is not a perfect country. It faces enormous challenges: air pollution, climate stress, inequality, urban congestion, and rural distress, among others. Addressing these problems requires sustained policy interventions, technological innovation, behavioural change, and time.

Complex issues such as air pollution cannot be resolved overnight, nor can they be meaningfully addressed through anger or violence. Confusion, disruption, and instability ultimately harm the very citizens — especially the youth — who seek a better future. For Gen Z in India, the real challenge is to remain informed, critically evaluate narratives circulating on social media and television, and channel their energy into constructive civic engagement rather than reactive mobilisation.

India’s strength has always been its ability to absorb dissent while maintaining democratic continuity. The youth of the country must guard against becoming instruments of manufactured outrage and instead emerge as stakeholders in long-term national progress. Genuine change lies not in destabilising institutions, but in strengthening them through awareness, responsibility, and informed participation.

Maninder Gill is Managing Director, Radio India, Surrey, Canada. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.