The Supreme Court on Wednesday questioned whether the Election Commission of India (ECI) possesses “untrammelled powers” to bypass established rules during its ongoing Special Intensive Revision (SIR)

of electoral rolls. A bench comprising Chief Justice of India Surya Kant and Justice Joymalya Bagchi observed that while the poll body has wide discretion under the Constitution, its actions must remain “just and fair”, and it cannot behave like an “unruly horse” that overrides the civil rights of registered voters.

The legal battle centres on Section 21(3) of the Representation of the People Act, 1950, which grants the ECI the power to direct a special revision of electoral rolls in “such manner as it may think fit”. Senior Advocate Rakesh Dwivedi, representing the ECI, argued that this provision “unshackles” the commission, allowing it to deviate from standard procedures—such as the Registration of Electors Rules, 1960—to ensure a clean and accurate voter list. The commission maintains that this intensive exercise is necessary to remove “logical discrepancies”, such as impossible age gaps between parents and children or ghost entries that “defy science”.

However, the bench expressed deep reservations about the lack of transparency in this “unique” power. Justice Bagchi pointed out that while Section 21(3) is wide, it is not “unlimited”. He questioned why the ECI had replaced the standard list of six documents required for voter verification with a new list of 11 specific documents, some of which are difficult for rural or poor voters to produce. The court noted that such “deviations” carry serious civil consequences, potentially disenfranchising legitimate citizens without following the principles of natural justice.

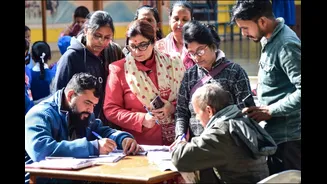

The context of the hearing is particularly charged in West Bengal, where nearly 1.36 crore voters—roughly 20 per cent of the electorate—have been flagged for “logical discrepancies” ahead of assembly elections. Critics and petitioners, including members of the Trinamool Congress, have alleged that the SIR is being used for “profiling” and has caused widespread “stress and strain” among the public. The court had previously ordered the ECI to publish the names of flagged voters at local panchayat offices rather than relying on opaque digital notices or WhatsApp communications.

As the hearings continue, the Supreme Court’s primary concern remains the balance between the ECI’s constitutional mandate under Article 324 to oversee elections and the statutory protections afforded to voters. By asking if the ECI’s power is “untrammelled”, the court has signalled that any “special” procedure must still be rooted in transparency and cannot unilaterally discard the rules set by Parliament.