Who maintains Stonehenge, one of Britain’s oldest and most visited monuments? Clue: it is not the UK government. Stonehenge and many other historic structures are maintained by English Heritage Trust,

which is neither a quango nor a government entity; it is a charity which is led mostly by people who have reached positions of eminence in the private sector. And no one can quibble that monuments are ineptly or inadequately conserved and preserved there.

Monuments in India are now set to be preserved and maintained by private entities who are major contributors to the National Culture Fund, via the expertise of government empanelled conservation architects in accordance with plans approved by the Archaeological Survey of India. The only aspect left to the discretion of private companies is the choice of agencies to execute the projects. As the ASI is under-staffed and cash strapped, this is a practical solution.

As it is, there have been periodic complaints, both from the general public and VIPs (including the PMO), about the poor state of maintenance of monuments and heritage sites under ASI “protection”. The glacial pace of government departments is known but the quality of ASI’s work has been under the scanner too as well as its internal capacity to physically man and maintain thousands of monuments. Partnership for funding and maintenance is a no-brainer.

Yet there is an outcry from predictable quarters that the government is simply hellbent on handing over priceless national heritage to private companies. This is a specious argument. Barring the Taj Mahal and a few other monuments, most “ASI-protected” historic places are sadly neglected, partly because there are far too many for individual attention and partly due to endemic sloth and corruption. Public funds rarely get monitored—by the public or by anyone else.

On the other hand, private entities and even individuals maintain a very close watch on the expenditure of their committed funds, whether on a personal project or a public one. Nor are they likely to allow the wilful depletion or deterioration of whatever those funds were spent on. So if they pour lakhs or crores into the conservation and preservation of a monument, they are likely to ensure the money is properly utilised and accounted for and the result is appreciated too!

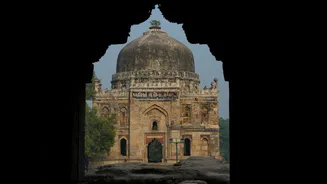

One of the best examples of private entities preserving monuments is the tomb of Mah Begum, the wife of Akbar’s favourite poet-general Abdur Rahim Khan-e-Khanan, in New Delhi’s Nizamuddin East. InterGlobe Foundation (whose parent company owns IndiGo airlines) provided the financial support while the Aga Khan Trust for Culture executed the conservation in association with ASI. No one can say the building was hijacked by either of the two private entities.

Moreover, the magnificent restoration of Humayun’s Tomb in the same area of New Delhi—now a UNESCO World Heritage Site—was primarily funded and executed by AKTC (in partnership with ASI) but also had significant financial contribution from the Tata Trusts. This public-private partnership to restore a major Mughal monument was green-flagged by the then Congress-led UPA government, which no one has ever accused of “selling off” heritage.

Also in Nizamuddin, the 16th-century Sabz Burj near Humayun’s Tomb was restored with funding from the lighting company Havells India as a Corporate Social Responsibility initiative, also executed by AKTC with ASI. The Tata Trusts also gave a ₹12 crore grant to AKTC for conservation of the Qutb Shahi Tombs complex in Hyderabad and the American Ambassador’s Fund for Cultural Preservation gave ₹60 lakh for archaeological investigations there.

These four projects highlight the positive potential of public-private partnerships to conserve monuments. Their generosity ensured that the best expertise and technology could be used for conservation and preservation, and the supervising agency remained the ASI. There is never any question of handing over ownership of national monuments. Why then are naysayers deriding a cement company for only lighting and maintaining Red Fort, already conserved by the ASI?

Critics of the Centre’s proposal for private participation in conservation and maintenance of Indian monuments are presumably aware that English Heritage Trust manages over 400 more historic sites besides Stonehenge and is the custodian of the National Heritage Collection. Historic England, the government-funded statutory body, handles protection. But no one has ever accused the British government of selling off national monuments to private entities!

Currently ASI is in charge of 3,685 to 3,698 sites of national importance, protected under the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act of 1958. This includes prehistoric and other excavation sites, tombs, temples, mosques, churches, stupas, forts, palaces, caves, stepwells, cemeteries, bridges and more. It also protects 24 of the 44 UNESCO World Heritage Sites in India. Another 4,134 sites are managed by archaeological departments of states.

In the 2025-26 Union Budget, ASI was given an allocation of ₹1278.49 crore, barely more than the 2024-25 amount of ₹1,273.91 crore. And it must be remembered that over 50% of its budgetary allocation is spent annually on salaries, wages, and administrative expenses of ASI’s 6,000 employees. So, how much is left for ASI to spend on proper conservation and protection of the monuments themselves, using the best expertise, materials and technology? Clearly very little.

However, there is a need to have a strict legal and legislated framework to ensure that there is never any mismanagement or mishandling of conservation by private entities, especially in the absence of official monitoring for any reason. While the prominent national monuments remain safe from any serious excesses as they are always in the media glare and public attention, many less-known sites (currently perhaps neglected) could be endangered by “over-conservation”.

A lot depends on the quality of oversight and conservation assessments by the ASI of the monuments chosen to be maintained by private entities, of course. There also has to be a certain degree of transparency about the extent of proposed conservation and maintenance measures. Local antiquities and heritage enthusiasts obviously need to remain vigilant too. Nothing should be done in an opaque manner as it then risks local opposition if not legal hurdles.

But there is no doubt that it is a timely proposal and India’s monuments, now languishing because of a shoe-string ASI budget, need more generous conservation and preservation efforts. As long as there is continuous public scrutiny and a responsive complaint redressal system to discourage deviation from the stated norms both by the private sector and the ASI, India’s priceless architectural and archaeological heritage will certainly benefit.

(The author is a freelance writer. Views expressed are personal and do not necessarily reflect those of News18.)