The Opposition, lacking an argument, cried itself hoarse that by changing the Mahatma Gandhi Rural Employment Guarantee (MGNREGA) scheme, the Narendra Modi government was insulting the Father of the Nation.

It was not a policy argument. It was an opinion which has no basis and cannot form part of an informed discussion on the need to revamp the rural employment scheme and align it with the larger vision of a ‘Viksit Bharat-2047’. Those who raised this point were themselves complicit in marginalising Mahatma Gandhi’s vision of rural employment and empowerment through Khadi.

When he became Prime Minister in 2014, Narendra Modi exposed how decades of neglect had pushed the Khadi industry to the margins of Indian governance and policy-making. Shorn of a roadmap and lacking a synergising vision, the KVIC was being used as a parking lot for select political protégés and cronies who felt left out.

Khadi embodied Mahatma Gandhi’s ideals. It represented his expectations from a free India, symbolised his vision of mass empowerment and prosperity, and actualised his commitment to India’s self-reliance. Yet those who claimed to be the Mahatma’s political and philosophical heirs paid lip service to his most cherished programme. They worked to make Khadi irrelevant in free India’s policy formulation.

Contrast that approach with Narendra Modi’s. In the last decade that he has been Prime Minister, Narendra Modi has led a historic turnaround in the Khadi sector. In the financial year 2024-25, the KVIC has seen a record turnover of Rs 1.70 lakh crore. In the last decade, KVIC’s production has increased nearly fourfold, while Khadi sales have gone up nearly six-fold. From 1.30 crore in 2013-14, the Khadi sector now employs 1.94 crore people. Going much beyond the symbolic, this is a real tribute to the vision of Mahatma Gandhi. The Opposition to Modi would obviously want us to overlook this reality because it makes them squirm. Their shouts in the name of Mahatma Gandhi are mere posturing and opposition for the sake of opposing.

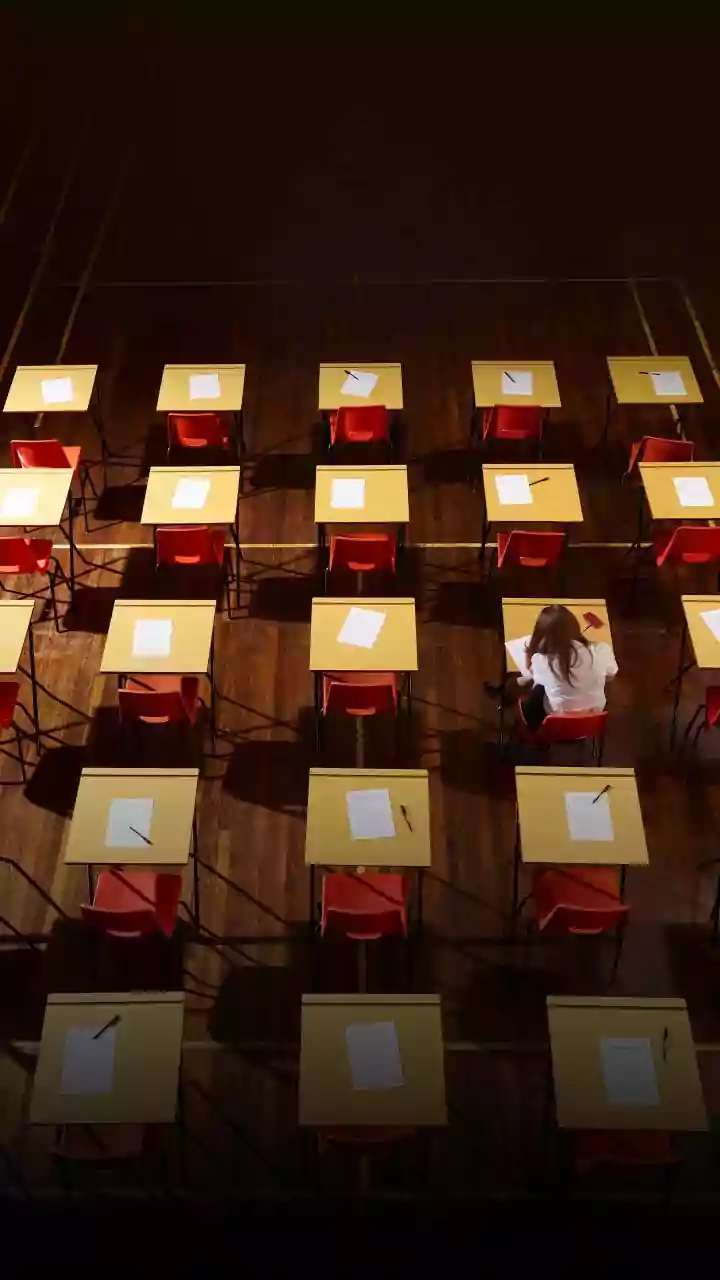

Launched in 2006, two decades is long enough to evaluate and assess the effectiveness of a scheme once touted as game-changing. The MGNREGA did provide relief in its early years and expanded rapidly. But its long-term impact dissipated due to weak governance structures, corruption, and the absence of a comprehensive and integrated development approach.

Plugging systemic leakages and reimagining last-mile delivery has been the hallmark of PM Modi’s governance for the last quarter century that he has held elected office. The need was for a structural overhaul and not a piecemeal restructuring.

The principal banes of MGNREGA were poor-quality and fragmented asset creation, and entrenched corruption and financial leakages. By 2014, when it resoundingly lost its mandate, the Congress-led UPA government was bogged down in deep corruption, with its energies flagging. Except for drumming up MGNREGA, it ignored the systemic deficiencies corroding the scheme.

Most MGNREGA works were undertaken in isolation, without being plugged into village or regional development goals. There were no durable or stable economic and social returns. Temporary roads, incomplete water structures and unplanned earthworks were created in an unplanned, non-integrated manner. These efforts did not contribute to the overall prosperity and growth of villages. On the other hand, entrenched corruption and financial leakages plagued the scheme in the absence of a strong verification mechanism. Public funds began to be widely misused. Fake and duplicate job cards, ghost beneficiaries, inflated or fabricated muster rolls, partial payment or complete denial of wages to workers became the new normal. Large-scale scams, with thousands of crores being siphoned off, came to light in states such as West Bengal, Telangana and Punjab.

The case of MGNREGA corruption in West Bengal came out glaringly when, in 19 districts, massive irregularities were uncovered between 2019 and 2022. Misappropriation of funds, absence of work at sites where work was supposed to have taken place, and irregular payments to beneficiaries were among the irregularities that came to light. The Calcutta High Court, in its observations while asking the Union government to resume MGNREGA in the state after the latter had imposed a hiatus following the uncovering of huge discrepancies, noted that the central government “are entitled to impose special conditions so as to ensure that whatever had occurred three years prior should not recur”, and that the “Central Government would be entitled to impose any other special conditions that would warrant and ensure that the Scheme is effectively and properly implemented in the State without giving any room for irregularity or illegality being committed.” It observed that the State, in this case the TMC-led West Bengal government, “shall comply with the directives in strict compliance and such directions which may be issued by the Central Government are non-negotiable…”

West Bengal, under the TMC dispensation, is a stark case in point of how the MGNREGA system was misused. Its evaluation was long overdue, and its comprehensive overhaul long required. VB-GRAM G’s significance must be seen against this nearly two-decade dominance of the previous scheme and its rampant misuse.

The expansion of workdays from 100 to 125 days of unskilled wage employment per rural household per year, and its agricultural sensitivity empowering states to declare an “Agricultural Pause” of up to 60 days during sowing and harvesting seasons without reducing the annual 125-day legal guarantee, balances farmer and labour interests.

The nature of works enumerated under VB-GRAM G is outcome-driven. Water-related works to ensure water security, core rural infrastructure-building activities, livelihood-related infrastructure, and special works to mitigate extreme weather events and enhance disaster preparedness have been prioritised to ensure that employment directly contributes to long-term rural productivity and resilience.

Some of the key points that set VB-GRAM G apart are its insistent framework of accountability and its objective of empowering states. Time-bound wage payments, with weekly wages to be paid no later than a fortnight, are mandated, with automatic compensation for delays. The scheme is genuinely sensitive to the needs and challenges of rural workers. The administrative expenditure ceiling has been raised to 9 per cent, ensuring adequate staffing, training and monitoring capacity, all of which had suffered under the UPA scheme. Overall allocations are higher, with states expected to gain approximately Rs 17,000 crore compared to MGNREGA. Some states, such as West Bengal under the TMC, which protested in Parliament, have conveniently hidden this dimension.

Oversight will be multi-layered. Six-monthly social audits will be compulsory, and a robust grievance redressal mechanism has been put in place. Failure to provide work, delayed wages or non-payment of allowances are recognised as enforceable offences. End-to-end transparency, elimination of corruption and misuse, and reduction of scope for ghost beneficiaries, fake works and financial manipulation are the cornerstones of VB-GRAM G. The biggest drawback of MGNREGA was that it institutionalised a web of financial manipulators and ghost beneficiaries who siphoned away legitimate benefits due to the truly marginalised. In states such as West Bengal, corruption and siphoning had become endemic.

Most arguments made against VB-GRAM G are political and do not stand policy scrutiny. The new scheme promises a comprehensive overhaul, leading to fundamental empowerment and long-term, sustainable transformation at the grassroots. It will eventually become one of the principal pillars of the Viksit Bharat edifice.

The author is Chairman, Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation, and a member of the National Executive Committee, BJP. The views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.