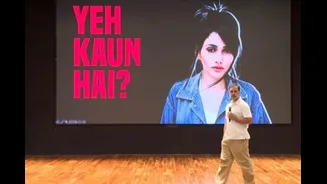

The controversy began on Wednesday, when Congress leader Rahul Gandhi alleged in a press conference that the 2024 Assembly elections in Haryana had been “stolen.” Holding up a photograph of a woman, he said

appeared 223 times on the voter list across two polling booths in Ambala district, Gandhi asked, “The EC needs to tell us how many times she voted.”

The woman was later identified as Charanjeet Kaur, a 75-year-old resident of Dhakola village in Ambala, who told The Indian Express she had voted only once. Her image was found repeated next to at least 255 names in two booths, an error villagers said had existed for years.

Gandhi also cited a separate example from the Rai constituency in Sonipat district, claiming that a stock image of a Brazilian model had been used to cast votes 22 times across 10 polling booths under different names. He said these instances proved a pattern of “vote chori” and “centralised manipulation” by the Election Commission and the BJP.

He further alleged that similar manipulation had disenfranchised voters in states such as Bihar’s Jamui district, where he said Dalit, backward-class and minority families had been removed from rolls without notice, calling it “a heartbreaking and shameful tragedy for democracy.”

In a post on X, the Congress leader wrote, “Today, I introduced the world to some people from Dharampur village in Jamui district of Bihar—what’s happening to them is the most heartbreaking and shameful tragedy for democracy. Despite submitting forms and necessary documents, the names of many villagers were removed from the voter list without any notice or reason.”

On Ground In Haryana: What The Cases Show

Among the examples Rahul Gandhi highlighted were cases from Dhakola village in Ambala and Rai constituency in Sonipat. What emerged was not evidence of organised impersonation, but of routine administrative lapses that appear to have persisted for years.

One of the women whose voter card circulated was displayed during the controversy, Pinky Juginder Kaushik of Haryana, told News18 she had personally voted despite the mismatch. “Yes, I went to cast my vote myself at the village school,” she said. “The names are the same, but there was a mistake with the photo. They used someone else’s picture. Nevertheless, I did vote.”

Her statement directly contradicted Gandhi’s claim that “fake identities” had been used to cast multiple votes.

In The Rai Constituency

In the Rai constituency, India Today identified five distinct cases featuring the so-called “Brazilian model” photo.

- Photo misprints, but voters voted themselves: Two women, including Pinky of Machroli village, said their photos had been printed incorrectly, but they cast their votes normally. “When I applied for my voter card after shifting from Delhi, it first arrived with a photo misprint,” Pinky said. “I still voted using my voter slip and Aadhaar card. There’s no vote chori here.”

- Another family, that of Munish, said her photo had been mismatched earlier but was corrected at the booth. “She cast her own vote. The error was in the slip, not in the vote,” her brother-in-law said.

- A deceased voter still on the list: Guniya, who died in March 2022, continued to appear on the 2024 voter list with the Brazilian woman’s photo attached. Her family produced her death certificate and said the record had not been updated.

- Duplicate and outdated entries: Another voter, Bimla, had two separate entries — one genuine and another with the same name and address but a different EPIC number and the Brazilian photo. Her son Pradeep said, “Whoever made this should be punished… This is a fraudulent work.”

- In a fifth case, Saroj, who moved to Bhiwani after marriage years ago, still appeared on the Rai list with the same Brazilian model image. Her family said she hadn’t voted there since 2001.

Taken together, the five cases point to clerical errors, outdated data, and duplicate records. No case was found where a voter was unable to vote due to the mismatch. Officials at the Sonipat district election office told India Today that photo mismatches may have occurred because of operator-level errors during voter data migration.

What Dhakola Village Revealed

At his presser, Rahul Gandhi displayed a photograph of a woman, claiming her image appeared 223 times on the voter list across two polling booths in Dhakola village, and asked, “The EC needs to tell us how many times she voted.”

The woman, identified as 75-year-old Charanjeet Kaur, told the Indian Express she had voted just once. Her photo was found next to at least 255 names across two booths, a long-standing error villagers said had existed for years.

Farmer Lakhmir Singh said his family’s voter ID cards carried the correct photos, but Charanjeet’s image appeared next to his and ten relatives’ names. “Every time I go to vote – whether it’s for the MLA, MP or sarpanch – the staff say my photograph isn’t in the list. Then I show them my voter ID and Aadhaar,” he said. Seven of his 11 family members, all affected by the mismatch, voted in the 2024 Assembly polls.

Charanjeet herself said polling agents and staff “laugh” every time she votes. “It’s not my fault my photograph appears for so many voters,” she told The Indian Express.

Barara (Ambala) Sub Divisional Magistrate-cum-Election Registration Officer told IE an inquiry was underway and photographs would be updated once voters filled Form 8. Haryana’s Chief Electoral Officer, A. Sreenivas, said the matter would be “thoroughly examined.”

The Pattern That Emerges

When viewed together, the cases show a pattern of recurring clerical and data management errors, not proof of organised “vote chori.”

- Photo mismatches: The same image attached to multiple records, or wrong photos printed on IDs.

- Duplicate and outdated entries: Deceased voters not deleted, and names of those who migrated still appearing on older lists.

- Long-standing lapses: Several affected voters said these errors had existed for years despite repeated complaints.

These gaps have less to do with intentional manipulation and more to do with the limitations of a vast, semi-digitised voter management system. The result is a patchy, error-prone database where one photograph or EPIC number can be replicated several times without triggering immediate correction, errors that can persist through multiple election cycles.

No documented case in either Ambala or Sonipat involved a voter being prevented from voting, nor did anyone report someone else casting their ballot. Yet the recurring irregularities show how India’s electoral records, when poorly updated, can blur the line between clerical oversight and potential misuse.

What Rahul Gandhi Alleged About SIR

A day later, in a video released on his YouTube channel, Gandhi broadened his charge, describing the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls as an “institutionalised chori.” He alleged that the Election Commission was “openly colluding with the BJP to carry out this theft” and that SIR’s purpose was to “take away the voting rights of the poor.”

Citing an internal Congress analysis of the Mahadevapura assembly segment in Karnataka, Gandhi claimed 1,00,250 votes were “stolen” through duplicate and invalid entries, fake addresses, bulk registrations under single addresses, invalid photographs, and misuse of Form 6 meant for new voters.

“They know that we have caught their chori, and that is why SIR has come,” he said. “SIR is an institutionalised chori.”

He went on to allege that such manipulation had affected “over 100 seats” nationally and said the Election Commission’s refusal to share full voter list data had reinforced suspicions of bias.

What It All Points To

Taken together, the ground findings from Haryana reveal an electoral infrastructure strained by scale and dependent on outdated data systems rather than deliberate electoral theft.

What Rahul Gandhi described as “vote chori” appears, in the cases examined so far, to be symptomatic of India’s voter roll hygiene crisis — one where old records, manual entries, and data migration glitches routinely create phantom or mismatched voters.