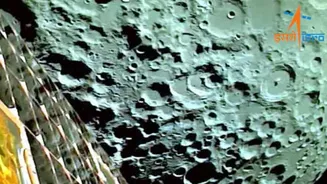

India has quietly taken its next giant leap in space.

The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) has begun the groundwork for building the Bharatiya Antariksh Station (BAS)—India’s own permanent space

station in low Earth orbit, envisioned as the country’s answer to the International Space Station (ISS).

News18 has learnt that ISRO’s Vikram Sarabhai Space Centre (VSSC) has formally invited Indian companies to help build the first module of the space station, marking the first concrete step towards putting Indians in a continuously inhabited space laboratory by 2035. The first module is expected to be launched in 2028.

ISRO has issued an Expression of Interest (EoI) calling on Indian aerospace manufacturing firms to develop two complete sets of the BAS-01 structure—the first module of the Bharatiya Antariksh Station.

This module will form the backbone of the future space station, which ISRO sees as the next logical step after the Gaganyaan human spaceflight programme.

In simple terms, this is where India moves from sending astronauts to space to living and working in space.

According to ISRO, the Bharatiya Antariksh Station represents India’s vision of a permanent human presence in space.

Once operational, BAS will serve as a space laboratory for long-duration experiments, enable advanced research in microgravity, and help India master technologies needed for future deep-space missions.

The long-term plan is to launch the first BAS module into orbit by 2028 and gradually expand it into a fully functional space station by 2035.

What Indian companies are being asked to build is no small piece of hardware.

Each module will be 3.8 metres in diameter, 8 metres tall, and will be built using high-strength aluminium alloy (AA-2219)—the same material used for human-rated space missions.

These structures must meet the same safety and quality standards as Gaganyaan, since astronauts will eventually live and work inside them.

ISRO wants two full sets of this module to be built on Earth before launch.

This is not ordinary manufacturing. The work demands extreme precision.

Companies must develop specialised welding and fabrication techniques and ensure near-perfect tolerances—errors of even half a millimetre are unacceptable.

They must also conduct pressure tests, leak tests, and nondestructive testing and follow strict “human-rated” quality protocols.

In short, this is among the most complex aerospace manufacturing assignments ever offered to the Indian industry.

ISRO has made one thing clear: this is an Indian-only effort.

There will be no financial assistance from the government to set up facilities, no outsourcing of critical processes like welding or final assembly, and strict oversight and approvals at every stage.

ISRO will supply Gaganyaan-qualified raw materials, detailed manufacturing drawings, and 3D models of all components.

But the responsibility to deliver flawless hardware lies entirely with the selected Indian firms.

This move signals a major shift in India’s space programme. ISRO is no longer just launching satellites or planning short astronaut missions. It is preparing for a future where Indians live, work, and conduct science in space for months at a time.

If timelines hold, the first piece of India’s space station could be in orbit by 2028—a milestone that would place India among an elite group of spacefaring nations.