“I don’t understand why the leader of the largest country on Earth needs a few more kilometres. This war is not about land; it’s about our independence,” Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy mockingly

said last week.

⚡️ Zelensky: I don’t understand why the leader of the largest country on Earth needs a few more kilometers.

“This war is not about land; it’s about our independence,” he said. pic.twitter.com/UeYcpL5Kvy

— NEXTA (@nexta_tv) October 19, 2025

On the face of it, Zelenskyy’s logic makes sense. Russia is the largest country in the world, twice the size of the US or China, five times that of India, and is about 70 Britains put together. Russia has 11 time zones!

Indeed, why would a country of that size haggle for more landmass?

A widely acclaimed book by Tim Marshall, Prisoners of Geography, puts that debate in perspective. It argues that Russia’s geopolitical strategy is driven by its unique and constraining geography.

“Vladimir Putin says he is a religious man… If so, he may well go to bed each night, say his prayers and ask God: ‘Why didn’t you put some mountains in Ukraine?’ If God had built mountains in Ukraine, then the great expanse of flatland that is the North European Plain would not be such encouraging territory from which to attack Russia repeatedly. As it is, Putin has no choice: he must at least attempt to control the flatlands to the west,” writes Marshall.

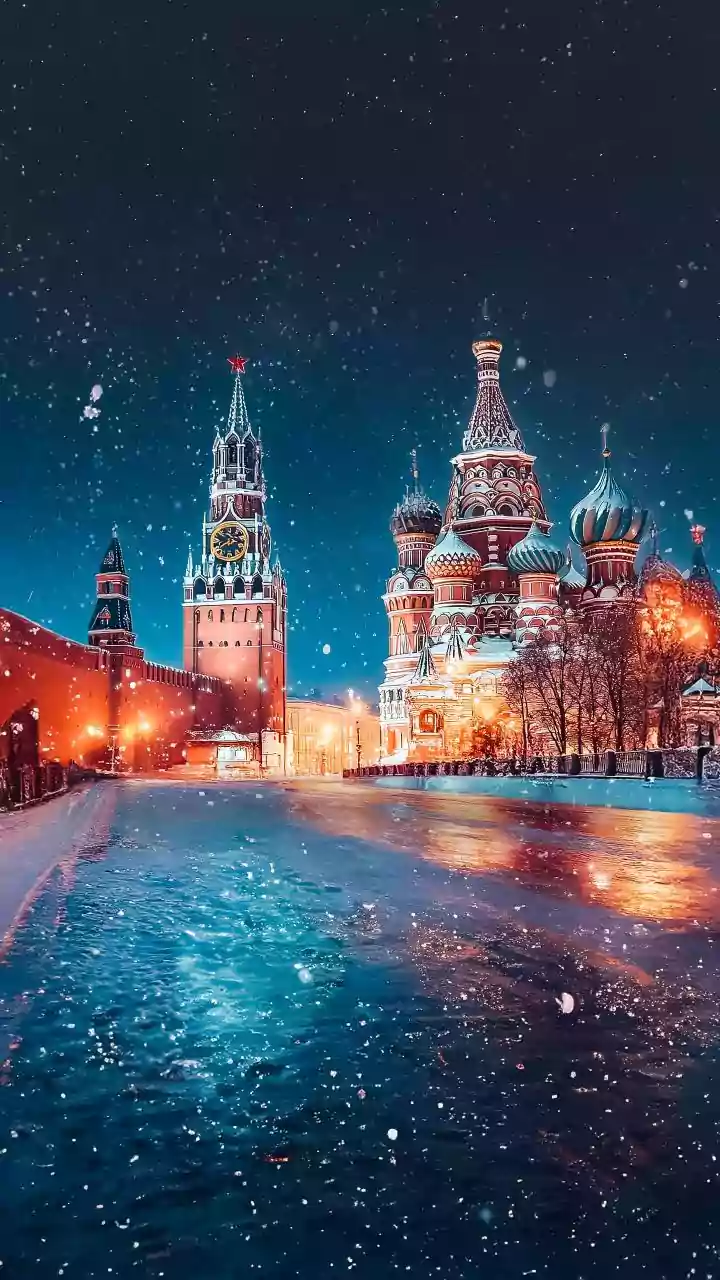

His book talks about how despite being the world’s largest country, Russia is geographically vulnerable. Its heartland — the area around Moscow and St Petersburg — lies on the North European Plain, which offers no natural barriers like mountains or deserts to block invasion from the West.

Besides, Russia has seen repeated invasions along this corridor by the most ruthless conquerors like Napoleon or Hitler. Although Russians always managed to vanquish them with grit and courage, this centuries-old threat creates a deep-seated sense of insecurity which underpins their foreign policy.

Then there is the geopolitical imperative. To protect itself, Russia has needed to focus on buffer states to the west like Ukraine, Poland, and the Baltic States for defensive depth.

“As long as a pro-Russian government held sway in Kiev, the Russians could be confident that its buffer zone would remain intact and guard the North European Plain. Even a studiedly neutral Ukraine, which would promise not to join the EU or NATO… would be acceptable,” Marshall writes. “But a pro-Western Ukraine with ambitions to join the two great Western alliances, and which threw into doubt Russia’s access to its Black Sea port?”

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia realised that its vast coastline is along the Arctic, and its primary ports (like Murmansk and Vladivostok) are icy almost year-round, harshly limiting its naval and commercial access to global trade routes.

The solution was Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014. By securing its only major warm-water naval base at Sevastopol on the Black Sea, it got to project power in the Mediterranean.

That brings Russia to the Donbas, made up of the eastern regions of Luhansk and Donetsk. Moscow now holds almost all of Luhansk and about 70 per cent of Donetsk.

Securing the Donbas is crucial for establishing a permanent land corridor between Russia and the Crimean Peninsula. Control over the Donbas, in particular the coastline further west towards Odesa port, threatens to land-lock Ukraine. If Russia grabs this port, it will finish Ukraine’s naval power and economic access to the Black Sea.

This is why Zelenskyy has reaffirmed that Ukraine would reject any proposal to leave the Donbas.

The context of the Ukraine war becomes clearer if one understands how Russia’s vastness is one of its biggest weaknesses. Moreover, nature has been mean towards Russia while dealing its cards.

Putin’s spring analogy best captures Russia’s response to its natural vulnerabilities. He explains his nation’s compulsions with signature bluntness: “Russia found itself in a position it could not retreat from. If you compress the spring all the way to its limit, it will snap back hard. You must always remember this.”

Abhijit Majumder is the author of the book, ‘India’s New Right’. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.