What is the story about?

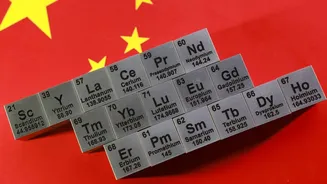

In an era defined by tariff wars and economic coercion, resource politics has become a key pillar to influence geopolitics. Traditionally, lack of resources was seen as a structural weakness for developing economies like India. It was seen as a vulnerability which left them dependent on the external suppliers. However, today India has adopted a different strategy of converting its scarcity into leverage and its dependency into cross-trade, diplomacy and industrial policy. India is not only acting as a passive buyer of resources, but it is also emerging as a key player in shaping a rules-based, diversified supply chain, and the recent example is India joining the US-led Pax-Silica.

Pax-Silica was unveiled by US President Donald Trump on December 11, 2025. The initial signatories are Australia, Greece, Israel, and Japan. Qatar, the Republic of Korea, Singapore, the UAE and the UK, while the non-signatory participants are Canada, the EU, the Netherlands, the OECD and Taiwan. This coalition aims to secure resilient and trusted supply chains for artificial intelligence (AI), energy, critical minerals and advanced manufacturing. The new US Ambassador Sergio Gor’s invitation to India to join the initiative showcases that the US recognises that India is an important player in securing resilient and trusted supply chains and advancing mutual economic prosperity, as US officials have acknowledged that India’s joining in the Pax-Silica supply chain is a historic milestone.

India’s pursuit of partnerships like Pax-Silica is emblematic of broader diplomatic recalibration. The global order, which was once dominated by Western economies and markets, has now been ruptured due to broader changes in the economic structures, growing demand for clean energy, the emergence of AI and the importance of critical minerals. In this context, India’s importance has grown due to its growing economic trajectory, its large market base and its ability to operate across varied geopolitical blocs without being subsumed by any single one.

A significant role for this recalibration has been India’s External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar. Jaishankar has constantly emphasised that globalisation has entered a phase where interdependence is no longer benign and that supply chains, trade regimes and technological competence are now new levers of power. His articulation of ‘multi-alignment’ reflects that India has to work with multiple partners on different issues. This is visible, as India is not only engaging with Western partners but is also engaging with Latin America and Africa, along with its neighbourhood, to secure supply chains and be a voice for the Global South.

India is not only actively engaging in proactive diplomacy but is also recalibrating its domestic economic policy. Today supply chains are no longer driven solely by efficiency but are also driven by political contingency. This has prompted India to rethink its position in the global supply chain, and rather than pursuing self-sufficiency in isolation, India has been focusing on selective capacity building in areas which are consequential, such as critical mineral processing, advanced materials, clean energy manufacturing, and digital infrastructure.

This approach has allowed India to reduce exposure to supply chain distortions while remaining embedded within global markets. Participation in initiatives such as Pax-Silica complements domestic efforts by enabling technology sharing, investment flows, and standards coordination, all of which are essential for scaling industrial capacity. At the same time, India’s engagement with resource-rich regions in Africa, Latin America, and Australia reflects a conscious effort to diversify sourcing and avoid over-concentration of dependencies.

Importantly, India’s strategy signals a shift from transactional resource acquisition to long-term supply-chain partnerships. These partnerships increasingly emphasise sustainability, value addition, and shared development outcomes, aligning India’s economic interests with broader global governance norms. As economic fragmentation deepens and resource access becomes a site of strategic competition, India’s ability to balance openness with resilience positions it not merely as a beneficiary of new supply chains but as an active architect of the emerging resource order.

(Trishala Anand Sancheti is Research Fellow at India Foundation. Views expressed are personal and solely those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect Firstpost’s views.)

Pax-Silica was unveiled by US President Donald Trump on December 11, 2025. The initial signatories are Australia, Greece, Israel, and Japan. Qatar, the Republic of Korea, Singapore, the UAE and the UK, while the non-signatory participants are Canada, the EU, the Netherlands, the OECD and Taiwan. This coalition aims to secure resilient and trusted supply chains for artificial intelligence (AI), energy, critical minerals and advanced manufacturing. The new US Ambassador Sergio Gor’s invitation to India to join the initiative showcases that the US recognises that India is an important player in securing resilient and trusted supply chains and advancing mutual economic prosperity, as US officials have acknowledged that India’s joining in the Pax-Silica supply chain is a historic milestone.

India’s pursuit of partnerships like Pax-Silica is emblematic of broader diplomatic recalibration. The global order, which was once dominated by Western economies and markets, has now been ruptured due to broader changes in the economic structures, growing demand for clean energy, the emergence of AI and the importance of critical minerals. In this context, India’s importance has grown due to its growing economic trajectory, its large market base and its ability to operate across varied geopolitical blocs without being subsumed by any single one.

A significant role for this recalibration has been India’s External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar. Jaishankar has constantly emphasised that globalisation has entered a phase where interdependence is no longer benign and that supply chains, trade regimes and technological competence are now new levers of power. His articulation of ‘multi-alignment’ reflects that India has to work with multiple partners on different issues. This is visible, as India is not only engaging with Western partners but is also engaging with Latin America and Africa, along with its neighbourhood, to secure supply chains and be a voice for the Global South.

India is not only actively engaging in proactive diplomacy but is also recalibrating its domestic economic policy. Today supply chains are no longer driven solely by efficiency but are also driven by political contingency. This has prompted India to rethink its position in the global supply chain, and rather than pursuing self-sufficiency in isolation, India has been focusing on selective capacity building in areas which are consequential, such as critical mineral processing, advanced materials, clean energy manufacturing, and digital infrastructure.

This approach has allowed India to reduce exposure to supply chain distortions while remaining embedded within global markets. Participation in initiatives such as Pax-Silica complements domestic efforts by enabling technology sharing, investment flows, and standards coordination, all of which are essential for scaling industrial capacity. At the same time, India’s engagement with resource-rich regions in Africa, Latin America, and Australia reflects a conscious effort to diversify sourcing and avoid over-concentration of dependencies.

Importantly, India’s strategy signals a shift from transactional resource acquisition to long-term supply-chain partnerships. These partnerships increasingly emphasise sustainability, value addition, and shared development outcomes, aligning India’s economic interests with broader global governance norms. As economic fragmentation deepens and resource access becomes a site of strategic competition, India’s ability to balance openness with resilience positions it not merely as a beneficiary of new supply chains but as an active architect of the emerging resource order.

(Trishala Anand Sancheti is Research Fellow at India Foundation. Views expressed are personal and solely those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect Firstpost’s views.)