What is the story about?

In a world now defined by fractured supply chains, technology rivalries and rising geopolitical risk, New Delhi has used the Union Budget for 2026-27 as a vehicle to recalibrate India’s economic priorities around security, self-sufficiency and long-term leverage.

In the Budget, presented by Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman on Sunday, critical minerals, nuclear energy, semiconductor manufacturing, maritime logistics, defence modernisation and data infrastructure all feature prominently.

At the core of the Budget’s narrative is the argument that 'atma nirbharta' has moved from being a developmental aspiration to a strategic necessity.

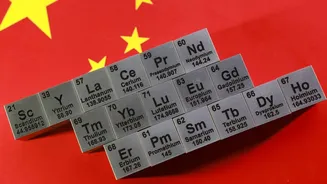

One of the most strategically significant announcements in Budget 2026 relates to rare earth minerals, which have become indispensable for advanced technologies ranging from electric vehicles and renewable energy systems to defence platforms and satellite infrastructure.

The government has announced the creation of four dedicated Rare Earth Mineral Corridors spanning Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh and Odisha states known for monazite-rich beach sand deposits.

India possesses approximately 6.9 million tonnes of rare-earth reserves, yet remains heavily dependent on imports, sourcing more than 45 per cent of its requirements from China.

This reliance has persisted due to limited domestic refining capacity and regulatory structures that historically constrained private participation. The new corridors are designed to address this imbalance by clustering extraction, processing, refining and downstream manufacturing in geographically integrated zones.

To support this transition, the government has operationalised a ₹7,280 crore incentive programme focused on rare-earth permanent magnets.

In addition, Indian Rare Earths Ltd, a state-owned enterprise, has been directed to supply 500 tonnes of rare-earth oxides annually to private manufacturers, a move intended to catalyse domestic value addition rather than the export of raw materials.

The urgency behind this push became evident in April 2025, when China imposed export restrictions on certain critical mineral processing technologies.

Given China’s control over nearly 90 per cent of the global permanent magnet supply, the decision had immediate consequences for Indian electric vehicle manufacturers and defence contractors.

By establishing rare earth corridors and delinking monazite mining from restrictive provisions under the Atomic Energy Act, the government is attempting to ensure that India’s industrial and defence sectors are insulated from sudden supply shocks.

The objective is not only to meet domestic demand but also to move India higher up the value chain, enabling the production of components essential for next-generation technologies.

Semiconductor manufacturing is an area that has gained strategic importance amid increasing competition between major technology powers. The finance minister announced

the next phase of the India Semiconductor Mission, referred to as ISM 2.0, with a new allocation of ₹40,000 crore.

The expanded mission builds on earlier efforts that have already resulted in the approval of 10 major semiconductor-related projects across six states, with cumulative investments amounting to ₹1.6 lakh crore.

While ISM 1.0 focused on attracting fabrication and assembly facilities, ISM 2.0 places greater emphasis on equipment manufacturing, materials, indigenous intellectual property and deeper integration into global supply chains.

Advanced chip design capabilities form a central pillar of the new phase. Work on 3-nanometer chip design is already underway in technology hubs such as Noida and Bengaluru, while emerging packaging technologies, including 3D glass solutions, have been identified as priority areas.

These initiatives are complemented by customs duty waivers on capital goods used in semiconductor manufacturing, a step expected to reduce initial project costs by an estimated 15 to 20 per cent.

The government’s approach reflects a recognition that semiconductors are no longer merely an industrial concern but a strategic asset.

Ongoing trade tensions and export controls between the United States and China have demonstrated how access to chips can be restricted for geopolitical reasons. By expanding domestic capabilities, India aims to reduce the risk of its digital economy becoming collateral damage in broader technology disputes.

Talent development has been explicitly linked to this strategy. The Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology plans to expand artificial intelligence training programmes to 500 universities nationwide.

Semiconductor-linked chip design curricula are already active in 315 institutions, with industry participation in curriculum development.

The government has extended basic customs duty exemptions on imports required for nuclear power projects until 2035. The exemption now applies across all nuclear plants, regardless of capacity, lowering the cost of specialised equipment that continues to be sourced internationally.

This fiscal measure aligns with broader policy efforts to reshape the nuclear sector. Proposed legislative changes, including the Atomic Energy Bill, 2025 — also referred to as the SHANTI Bill — seek to permit private participation in nuclear power development under defined safety and liability frameworks.

Historically, civil nuclear operations have been the exclusive domain of the state under the Atomic Energy Act of 1962.

Under the Nuclear Energy Mission for Viksit Bharat, India has set an ambitious target of expanding nuclear capacity from its current level of approximately 8.8 GW to 22 GW by 2032 and 100 GW by 2047.

A key component of this strategy is the promotion of 220 MWe pressurised heavy water reactors, branded as Bharat Small Reactors.

For the first time, large industrial users such as steel and aluminium producers will be allowed to fund and provide land for these reactors, while Nuclear Power Corporation of India Ltd retains operational control.

The aim is to replace coal-based captive power plants with small modular reactors, thereby reducing exposure to imported fossil fuel volatility and future carbon border adjustment mechanisms imposed by jurisdictions such as the European Union.

One of the most notable announcements is a ₹10,000 crore scheme spread over five years to establish a globally competitive shipping container manufacturing industry in India.

Currently, nearly 90 per cent of the world’s shipping containers are produced by Chinese manufacturers, a concentration that became acutely problematic during the Red Sea crisis in late 2025.

During that period, Indian vessels were forced to reroute around the Cape of Good Hope, adding approximately 3,000 nautical miles and 10 to 15 days to transit times.

The government’s container manufacturing initiative aims to scale domestic production to 600,000 twenty-foot equivalent units annually by 2029. Manufacturing hubs are expected to develop in industrial centres such as Bhavnagar in Gujarat.

The container push is embedded within a broader logistics strategy. The Budget outlines plans to operationalise 20 new National Waterways over the next five years, beginning with National Waterway-5 in Odisha, which will link mineral-rich regions with major ports.

A new Dedicated Freight Corridor connecting Dankuni and Surat is intended to improve east-west cargo movement and reduce transit times.

Additional measures include the development of ship-repair ecosystems in Varanasi and Patna, the establishment of skill centres along inland waterways, and the introduction of a Coastal Cargo Promotion Scheme aimed at doubling the share of inland and coastal shipping by 2047.

The government has also proposed to indigenise seaplane manufacturing, supported by a viability gap funding scheme, to improve connectivity to remote regions and boost tourism.

India’s defence allocation for 2026-27 reflects a continued emphasis on military modernisation and preparedness.

The total defence outlay has been increased to approximately ₹7.8 lakh crore, representing a rise of around 15 per cent over the previous year. Capital expenditure for modernisation has grown by nearly 22 per cent to ₹2.19 lakh crore, marking the highest-ever allocation for new equipment acquisition.

Major procurement programmes are in the pipeline, including fighter aircraft, submarines and unmanned aerial systems. Specific allocations include ₹63,733 crore for aircraft procurement and ₹25,023 crore for naval platforms such as submarines and carrier-based fighters.

Recent procurement approvals, valued at around ₹80,000 crore, have been largely restricted to domestically produced systems, reinforcing the emphasis on indigenisation.

Revenue expenditure for the armed forces has also increased, while defence pensions now stand at ₹1.71 lakh crore. In contrast, the defence (civil) budget has seen a marginal reduction of 0.45 per cent.

The Budget also proposes exemptions on basic customs duty for raw materials used in the manufacture of aircraft parts intended for maintenance, repair and overhaul within the defence sector.

Other tariff-related measures include reductions in duties on personal imports in response to US trade actions, as well as an increase in duty-free import limits for inputs used in seafood processing for export.

Basic customs duty exemptions have also been extended to capital goods used in the manufacture of lithium-ion cells and critical minerals.

Among the most forward-looking announcements in Budget 2026 is the introduction of a tax holiday extending until 2047 for foreign firms providing global cloud services through data centres located in India.

To qualify, such firms must serve Indian customers via domestic reseller entities, ensuring local compliance and oversight.

The incentive offers zero corporate tax on global revenues generated from cloud infrastructure based in India, providing long-term certainty to technology companies.

The policy aligns with India’s ambition to anchor global computing capacity within its borders and compete with established data hubs such as Singapore and Dubai.

Technology firms have already begun responding. Google has committed $15 billion to develop an artificial intelligence-focused data centre in Visakhapatnam, starting with a one-gigawatt capacity.

Complementary measures include a safe harbour regime for non-resident firms using bonded warehouses for electronic components, with profits capped at 2 per cent of invoice value, and a common safe harbour margin of 15.5 per cent for IT services, with the threshold raised substantially.

Hosting critical data and compute infrastructure is viewed as a source of geopolitical leverage in an era where data has become a foundational resource.

From minerals and microchips to ships and servers, the Budget reflects an understanding that economic resilience is central to national power in an increasingly contested global environment.

With inputs from agencies

In the Budget, presented by Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman on Sunday, critical minerals, nuclear energy, semiconductor manufacturing, maritime logistics, defence modernisation and data infrastructure all feature prominently.

At the core of the Budget’s narrative is the argument that 'atma nirbharta' has moved from being a developmental aspiration to a strategic necessity.

How geopolitics drove India's Union Budget 2026-27

Rare earths and mineral sovereignty

One of the most strategically significant announcements in Budget 2026 relates to rare earth minerals, which have become indispensable for advanced technologies ranging from electric vehicles and renewable energy systems to defence platforms and satellite infrastructure.

The government has announced the creation of four dedicated Rare Earth Mineral Corridors spanning Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh and Odisha states known for monazite-rich beach sand deposits.

India possesses approximately 6.9 million tonnes of rare-earth reserves, yet remains heavily dependent on imports, sourcing more than 45 per cent of its requirements from China.

This reliance has persisted due to limited domestic refining capacity and regulatory structures that historically constrained private participation. The new corridors are designed to address this imbalance by clustering extraction, processing, refining and downstream manufacturing in geographically integrated zones.

To support this transition, the government has operationalised a ₹7,280 crore incentive programme focused on rare-earth permanent magnets.

In addition, Indian Rare Earths Ltd, a state-owned enterprise, has been directed to supply 500 tonnes of rare-earth oxides annually to private manufacturers, a move intended to catalyse domestic value addition rather than the export of raw materials.

The urgency behind this push became evident in April 2025, when China imposed export restrictions on certain critical mineral processing technologies.

Given China’s control over nearly 90 per cent of the global permanent magnet supply, the decision had immediate consequences for Indian electric vehicle manufacturers and defence contractors.

By establishing rare earth corridors and delinking monazite mining from restrictive provisions under the Atomic Energy Act, the government is attempting to ensure that India’s industrial and defence sectors are insulated from sudden supply shocks.

The objective is not only to meet domestic demand but also to move India higher up the value chain, enabling the production of components essential for next-generation technologies.

Semiconductors, the next step

Semiconductor manufacturing is an area that has gained strategic importance amid increasing competition between major technology powers. The finance minister announced

The expanded mission builds on earlier efforts that have already resulted in the approval of 10 major semiconductor-related projects across six states, with cumulative investments amounting to ₹1.6 lakh crore.

While ISM 1.0 focused on attracting fabrication and assembly facilities, ISM 2.0 places greater emphasis on equipment manufacturing, materials, indigenous intellectual property and deeper integration into global supply chains.

Advanced chip design capabilities form a central pillar of the new phase. Work on 3-nanometer chip design is already underway in technology hubs such as Noida and Bengaluru, while emerging packaging technologies, including 3D glass solutions, have been identified as priority areas.

These initiatives are complemented by customs duty waivers on capital goods used in semiconductor manufacturing, a step expected to reduce initial project costs by an estimated 15 to 20 per cent.

The government’s approach reflects a recognition that semiconductors are no longer merely an industrial concern but a strategic asset.

Ongoing trade tensions and export controls between the United States and China have demonstrated how access to chips can be restricted for geopolitical reasons. By expanding domestic capabilities, India aims to reduce the risk of its digital economy becoming collateral damage in broader technology disputes.

Talent development has been explicitly linked to this strategy. The Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology plans to expand artificial intelligence training programmes to 500 universities nationwide.

Semiconductor-linked chip design curricula are already active in 315 institutions, with industry participation in curriculum development.

Nuclear energy and long-term power security

The government has extended basic customs duty exemptions on imports required for nuclear power projects until 2035. The exemption now applies across all nuclear plants, regardless of capacity, lowering the cost of specialised equipment that continues to be sourced internationally.

This fiscal measure aligns with broader policy efforts to reshape the nuclear sector. Proposed legislative changes, including the Atomic Energy Bill, 2025 — also referred to as the SHANTI Bill — seek to permit private participation in nuclear power development under defined safety and liability frameworks.

Historically, civil nuclear operations have been the exclusive domain of the state under the Atomic Energy Act of 1962.

Under the Nuclear Energy Mission for Viksit Bharat, India has set an ambitious target of expanding nuclear capacity from its current level of approximately 8.8 GW to 22 GW by 2032 and 100 GW by 2047.

A key component of this strategy is the promotion of 220 MWe pressurised heavy water reactors, branded as Bharat Small Reactors.

For the first time, large industrial users such as steel and aluminium producers will be allowed to fund and provide land for these reactors, while Nuclear Power Corporation of India Ltd retains operational control.

The aim is to replace coal-based captive power plants with small modular reactors, thereby reducing exposure to imported fossil fuel volatility and future carbon border adjustment mechanisms imposed by jurisdictions such as the European Union.

Logistics, container manufacturing and maritime resilience

One of the most notable announcements is a ₹10,000 crore scheme spread over five years to establish a globally competitive shipping container manufacturing industry in India.

Currently, nearly 90 per cent of the world’s shipping containers are produced by Chinese manufacturers, a concentration that became acutely problematic during the Red Sea crisis in late 2025.

During that period, Indian vessels were forced to reroute around the Cape of Good Hope, adding approximately 3,000 nautical miles and 10 to 15 days to transit times.

The government’s container manufacturing initiative aims to scale domestic production to 600,000 twenty-foot equivalent units annually by 2029. Manufacturing hubs are expected to develop in industrial centres such as Bhavnagar in Gujarat.

The container push is embedded within a broader logistics strategy. The Budget outlines plans to operationalise 20 new National Waterways over the next five years, beginning with National Waterway-5 in Odisha, which will link mineral-rich regions with major ports.

A new Dedicated Freight Corridor connecting Dankuni and Surat is intended to improve east-west cargo movement and reduce transit times.

Additional measures include the development of ship-repair ecosystems in Varanasi and Patna, the establishment of skill centres along inland waterways, and the introduction of a Coastal Cargo Promotion Scheme aimed at doubling the share of inland and coastal shipping by 2047.

The government has also proposed to indigenise seaplane manufacturing, supported by a viability gap funding scheme, to improve connectivity to remote regions and boost tourism.

Defence spending

India’s defence allocation for 2026-27 reflects a continued emphasis on military modernisation and preparedness.

The total defence outlay has been increased to approximately ₹7.8 lakh crore, representing a rise of around 15 per cent over the previous year. Capital expenditure for modernisation has grown by nearly 22 per cent to ₹2.19 lakh crore, marking the highest-ever allocation for new equipment acquisition.

Major procurement programmes are in the pipeline, including fighter aircraft, submarines and unmanned aerial systems. Specific allocations include ₹63,733 crore for aircraft procurement and ₹25,023 crore for naval platforms such as submarines and carrier-based fighters.

Recent procurement approvals, valued at around ₹80,000 crore, have been largely restricted to domestically produced systems, reinforcing the emphasis on indigenisation.

Revenue expenditure for the armed forces has also increased, while defence pensions now stand at ₹1.71 lakh crore. In contrast, the defence (civil) budget has seen a marginal reduction of 0.45 per cent.

The Budget also proposes exemptions on basic customs duty for raw materials used in the manufacture of aircraft parts intended for maintenance, repair and overhaul within the defence sector.

Other tariff-related measures include reductions in duties on personal imports in response to US trade actions, as well as an increase in duty-free import limits for inputs used in seafood processing for export.

Basic customs duty exemptions have also been extended to capital goods used in the manufacture of lithium-ion cells and critical minerals.

The 2047 tax holiday and India’s data ambitions

Among the most forward-looking announcements in Budget 2026 is the introduction of a tax holiday extending until 2047 for foreign firms providing global cloud services through data centres located in India.

To qualify, such firms must serve Indian customers via domestic reseller entities, ensuring local compliance and oversight.

The incentive offers zero corporate tax on global revenues generated from cloud infrastructure based in India, providing long-term certainty to technology companies.

The policy aligns with India’s ambition to anchor global computing capacity within its borders and compete with established data hubs such as Singapore and Dubai.

Technology firms have already begun responding. Google has committed $15 billion to develop an artificial intelligence-focused data centre in Visakhapatnam, starting with a one-gigawatt capacity.

Complementary measures include a safe harbour regime for non-resident firms using bonded warehouses for electronic components, with profits capped at 2 per cent of invoice value, and a common safe harbour margin of 15.5 per cent for IT services, with the threshold raised substantially.

Hosting critical data and compute infrastructure is viewed as a source of geopolitical leverage in an era where data has become a foundational resource.

From minerals and microchips to ships and servers, the Budget reflects an understanding that economic resilience is central to national power in an increasingly contested global environment.

With inputs from agencies