What is the story about?

The United States has introduced a major overhaul of its national dietary guidelines.

Announced on Wednesday, by the Trump administration, the updated recommendations place greater emphasis on protein, full-fat dairy, and certain fats, while calling for stricter limits on added sugar and processed foods.

Grains, once considered the foundation of a balanced diet, have been reduced to a smaller role.

The revised guidelines, issued jointly by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Department of Agriculture (USDA), form the basis for federal nutrition programmes, including school meals for nearly 30 million children, as well as public health advice and disease prevention strategies nationwide.

Officials say the changes reflect the “Make America Healthy Again” (Maha) agenda, led by US Health Secretary Robert F Kennedy Jr, and are intended to address rising rates of chronic illness linked to diet.

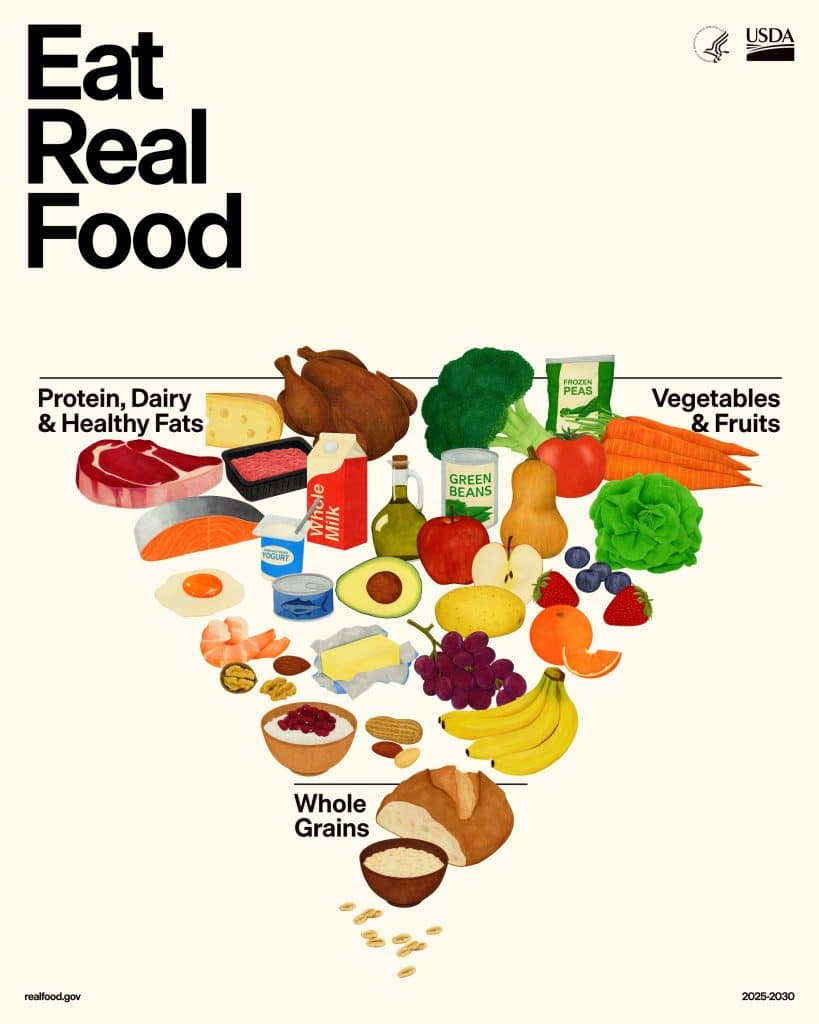

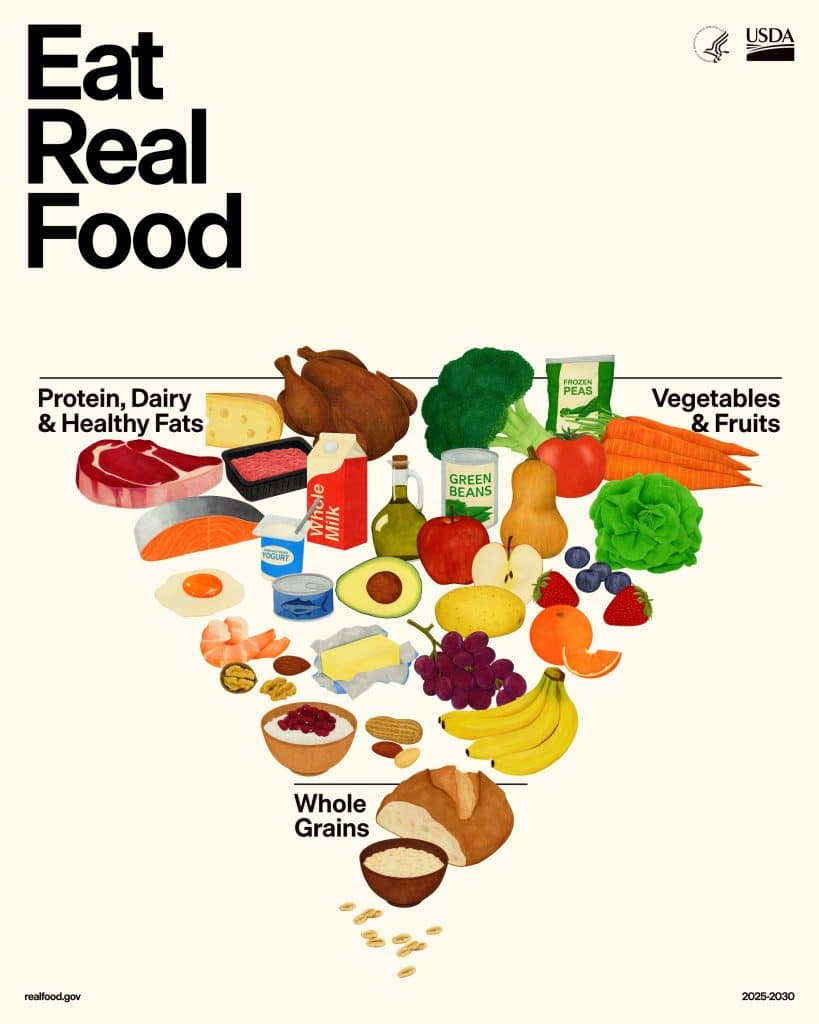

Alongside the updated recommendations, the federal government has revived the traditional food pyramid graphic — abandoned in 2011 — and inverted its structure.

The new visual places protein, dairy, healthy fats, fruits, and vegetables at the top, indicating they should make up the largest share of daily intake, while grains now appear at the bottom.

The new version flips the hierarchy.

In the revised pyramid, the foods Americans are encouraged to eat most frequently appear at the top of an upside-down triangle.

These include protein sources, dairy, healthy fats, fruits, and vegetables. Items that should be consumed less often — particularly grains — are now placed at the bottom.

White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt said the new guidelines reflect the administration’s broader health strategy under President Donald Trump.

“As Secretary of Health and Human Services, my message is clear: eat real food,” Kennedy said during a press briefing, calling the update “the most significant reset of federal nutrition policy in history.”

The United States originally adopted the food pyramid in 1992. That version promoted 6 to 11 servings of grains and starches per day, followed by moderate amounts of vegetables, fruits, dairy, and protein, with fats and sweets recommended sparingly.

In 2005, the USDA introduced “MyPyramid,” which retained the triangular shape but used vertical colour bands to represent food groups.

In 2011, the government moved to the “MyPlate” model, replacing the pyramid with a plate divided into sections for fruits, vegetables, grains, protein, and dairy.

Adults are now advised to consume between 1.2 and 1.6 grammes of protein per kilogram of body weight per day. This is a substantial rise from the long-standing recommendation of 0.8 grammes per kilogram.

The guidelines also note that proteins can be prepared with “salt, spices, and herbs” if desired.

Previously, protein did not even appear as a standalone category in the food pyramid until 2011, and it was still recommended in relatively smaller amounts.

Critics argue that Americans already consume sufficient protein and that the shift may encourage higher intake of red meat and full-fat dairy, making it harder to stay within recommended limits for saturated fat.

Another major departure from earlier guidance involves dairy and fat consumption. For decades, Americans were advised to choose low-fat or fat-free dairy products to reduce saturated fat intake.

The new guidelines now recommend three servings of full-fat dairy per day.

Kennedy has criticised earlier advice as outdated. He has also publicly expressed support for saturated fats.

In March last year, he visited a Florida Steak ‘n Shake after the restaurant chain replaced vegetable oil with beef tallow. Later, in July, he told governors that the updated guidelines would promote what he described as “commonsense” foods, including more saturated fats and meat.

Despite this shift in tone, the numeric limit on saturated fat remains unchanged. The new guidelines still cap saturated fat intake at less than 10 per cent of total daily calories.

In addition to dairy, the guidelines now encourage the consumption of “healthy” fats, including saturated fats from natural, whole-food sources such as avocado. These fats are placed at the top of the new food pyramid alongside protein and dairy.

The USDA has described this change as “ending the war on saturated fats,” although health authorities continue to caution against excessive intake.

The new dietary guidelines state that “no amount of added sugars or non-nutritive sweeteners is recommended or considered part of a healthy or nutritious diet.”

If consumed at all, added sugars should not exceed 10 grammes per meal.

Earlier guidance allowed small amounts of added sugar as long as total daily intake stayed below 10 per cent of calories. The new approach is meant to reflect growing concern about the link between sugar consumption and chronic disease.

“Today, our government declares war on added sugar,” Kennedy said during the White House announcement.

The updated guidance also discourages foods and drinks that contain artificial flavours, low-calorie sweeteners, and dyes.

Officials have pointed to the high intake of sugar and processed foods in the American diet as contributors to rising rates of obesity, diabetes, and other long-term health conditions.

Some food companies have already begun removing artificial ingredients in response to the administration’s priorities.

The guidelines strongly discourage the consumption of highly processed foods, particularly those with artificial additives. However, they stop short of formally defining what qualifies as “ultra-processed.”

HHS and the USDA have said they are working on creating a federal definition for ultra-processed foods.

Scientists worldwide have warned that such foods — often made with industrial ingredients and additives — are associated with poorer health outcomes, including higher risks of type 2 diabetes and obesity.

Another change in the updated guidelines concerns alcohol consumption. Previous federal recommendations set specific limits, advising no more than one drink per day for women and two for men.

The new guidance removes these numerical thresholds. Instead, it simply states that adults should “consume less alcohol for better overall health.”

“The Guidelines affirm that food is medicine and offer clear direction patients and physicians can use to improve health,” Dr. Bobby Mukkamala, president of the AMA, said in a statement.

The American Heart Association (AHA) said it “commends” the inclusion of several science-based recommendations in the new guidance, including eating more fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, while reducing added sugars and processed foods.

However, the organisation expressed concern about certain aspects of the advice.

“We are concerned that recommendations regarding salt seasoning and red meat consumption could inadvertently lead consumers to exceed recommended limits for sodium and saturated fats, which are primary drivers of cardiovascular disease,” the AHA said in a statement.

The AMA, by contrast, strongly supported the focus on ultraprocessed foods, sugar, and sodium, linking them to chronic illnesses such as heart disease, diabetes, and obesity.

Marion Nestle, professor emerita of nutrition, food studies and public health at New York University, also acknowledged the improvement in this area, in an email.

She said the advice to limit highly processed foods is “a major improvement” but criticised much of the rest of the guidance.

She argued that the emphasis on protein “makes no sense (Americans eat plenty) other than as an excuse to advise more meat and dairy, full fat, which will make it impossible to keep saturated fat to 10 per cent of calories or less.”

A White House official said the guidelines are based on sound science and are expected to support better public health outcomes as they are implemented across federal programmes.

The new guidelines have placed increased pressure on major food and beverage companies, particularly those that sell sugary drinks, snacks, and processed foods.

Soda makers such as Coca-Cola and PepsiCo, as well as snack producers like Mondelez — which manufactures Oreo cookies — have faced scrutiny from Kennedy. European-based food giants Nestlé and Danone are also affected by the policy shift.

The American Beverage Association responded by noting that nearly 60 per cent of beverages sold in the US contain no sugar. It argued that discouraging sugar-free beverages is “impractical and inherently contradictory.”

Despite the criticism, some manufacturers have begun adjusting product formulations to align with the administration’s emphasis on fewer artificial ingredients.

The dietary overhaul is part of the Trump administration’s broader “Make America Healthy Again” initiative, a social movement that backs Kennedy’s leadership at HHS.

The agenda also includes controversial measures such as curbing childhood vaccines and limiting access to unhealthy foods for people receiving food assistance.

Kennedy and US Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins had pledged to simplify the dietary guidelines and reduce what they described as the influence of food companies over federal nutrition advice.

The new dietary changes will affect school meals across the country. The School Nutrition Association said that school meals already include fruits, vegetables, and other healthy foods in line with existing federal standards.

However, the group added that schools need more funding and training to expand from-scratch cooking and further improve meal quality.

Kennedy has linked the new guidelines to the goal of reducing healthcare spending, an issue that is expected to feature prominently in the 2026 US midterm elections.

“The new guidelines recognise that whole nutrient-dense food is the most effective path to better health and lower healthcare costs,” he said.

Healthcare affordability is a key concern for Republicans, and the administration has framed the dietary overhaul as a preventive strategy that could reduce long-term medical expenses associated with chronic disease.

With inputs from agencies

Announced on Wednesday, by the Trump administration, the updated recommendations place greater emphasis on protein, full-fat dairy, and certain fats, while calling for stricter limits on added sugar and processed foods.

Grains, once considered the foundation of a balanced diet, have been reduced to a smaller role.

The revised guidelines, issued jointly by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Department of Agriculture (USDA), form the basis for federal nutrition programmes, including school meals for nearly 30 million children, as well as public health advice and disease prevention strategies nationwide.

Officials say the changes reflect the “Make America Healthy Again” (Maha) agenda, led by US Health Secretary Robert F Kennedy Jr, and are intended to address rising rates of chronic illness linked to diet.

Alongside the updated recommendations, the federal government has revived the traditional food pyramid graphic — abandoned in 2011 — and inverted its structure.

The new visual places protein, dairy, healthy fats, fruits, and vegetables at the top, indicating they should make up the largest share of daily intake, while grains now appear at the bottom.

How the new food pyramid turns decades of guidance upside down

The new version flips the hierarchy.

In the revised pyramid, the foods Americans are encouraged to eat most frequently appear at the top of an upside-down triangle.

These include protein sources, dairy, healthy fats, fruits, and vegetables. Items that should be consumed less often — particularly grains — are now placed at the bottom.

White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt said the new guidelines reflect the administration’s broader health strategy under President Donald Trump.

“As Secretary of Health and Human Services, my message is clear: eat real food,” Kennedy said during a press briefing, calling the update “the most significant reset of federal nutrition policy in history.”

The United States originally adopted the food pyramid in 1992. That version promoted 6 to 11 servings of grains and starches per day, followed by moderate amounts of vegetables, fruits, dairy, and protein, with fats and sweets recommended sparingly.

In 2005, the USDA introduced “MyPyramid,” which retained the triangular shape but used vertical colour bands to represent food groups.

In 2011, the government moved to the “MyPlate” model, replacing the pyramid with a plate divided into sections for fruits, vegetables, grains, protein, and dairy.

Protein takes centre stage in the American diet

Adults are now advised to consume between 1.2 and 1.6 grammes of protein per kilogram of body weight per day. This is a substantial rise from the long-standing recommendation of 0.8 grammes per kilogram.

The guidelines also note that proteins can be prepared with “salt, spices, and herbs” if desired.

Previously, protein did not even appear as a standalone category in the food pyramid until 2011, and it was still recommended in relatively smaller amounts.

Critics argue that Americans already consume sufficient protein and that the shift may encourage higher intake of red meat and full-fat dairy, making it harder to stay within recommended limits for saturated fat.

Changing views on fat

Another major departure from earlier guidance involves dairy and fat consumption. For decades, Americans were advised to choose low-fat or fat-free dairy products to reduce saturated fat intake.

The new guidelines now recommend three servings of full-fat dairy per day.

Kennedy has criticised earlier advice as outdated. He has also publicly expressed support for saturated fats.

In March last year, he visited a Florida Steak ‘n Shake after the restaurant chain replaced vegetable oil with beef tallow. Later, in July, he told governors that the updated guidelines would promote what he described as “commonsense” foods, including more saturated fats and meat.

Despite this shift in tone, the numeric limit on saturated fat remains unchanged. The new guidelines still cap saturated fat intake at less than 10 per cent of total daily calories.

In addition to dairy, the guidelines now encourage the consumption of “healthy” fats, including saturated fats from natural, whole-food sources such as avocado. These fats are placed at the top of the new food pyramid alongside protein and dairy.

The USDA has described this change as “ending the war on saturated fats,” although health authorities continue to caution against excessive intake.

Sugar restrictions tightened

The new dietary guidelines state that “no amount of added sugars or non-nutritive sweeteners is recommended or considered part of a healthy or nutritious diet.”

If consumed at all, added sugars should not exceed 10 grammes per meal.

Earlier guidance allowed small amounts of added sugar as long as total daily intake stayed below 10 per cent of calories. The new approach is meant to reflect growing concern about the link between sugar consumption and chronic disease.

“Today, our government declares war on added sugar,” Kennedy said during the White House announcement.

The updated guidance also discourages foods and drinks that contain artificial flavours, low-calorie sweeteners, and dyes.

Officials have pointed to the high intake of sugar and processed foods in the American diet as contributors to rising rates of obesity, diabetes, and other long-term health conditions.

Some food companies have already begun removing artificial ingredients in response to the administration’s priorities.

Highly processed foods under the lens

The guidelines strongly discourage the consumption of highly processed foods, particularly those with artificial additives. However, they stop short of formally defining what qualifies as “ultra-processed.”

HHS and the USDA have said they are working on creating a federal definition for ultra-processed foods.

Scientists worldwide have warned that such foods — often made with industrial ingredients and additives — are associated with poorer health outcomes, including higher risks of type 2 diabetes and obesity.

Alcohol advice becomes less specific

Another change in the updated guidelines concerns alcohol consumption. Previous federal recommendations set specific limits, advising no more than one drink per day for women and two for men.

The new guidance removes these numerical thresholds. Instead, it simply states that adults should “consume less alcohol for better overall health.”

How experts have reacted

“The Guidelines affirm that food is medicine and offer clear direction patients and physicians can use to improve health,” Dr. Bobby Mukkamala, president of the AMA, said in a statement.

The American Heart Association (AHA) said it “commends” the inclusion of several science-based recommendations in the new guidance, including eating more fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, while reducing added sugars and processed foods.

However, the organisation expressed concern about certain aspects of the advice.

“We are concerned that recommendations regarding salt seasoning and red meat consumption could inadvertently lead consumers to exceed recommended limits for sodium and saturated fats, which are primary drivers of cardiovascular disease,” the AHA said in a statement.

The AMA, by contrast, strongly supported the focus on ultraprocessed foods, sugar, and sodium, linking them to chronic illnesses such as heart disease, diabetes, and obesity.

Marion Nestle, professor emerita of nutrition, food studies and public health at New York University, also acknowledged the improvement in this area, in an email.

She said the advice to limit highly processed foods is “a major improvement” but criticised much of the rest of the guidance.

She argued that the emphasis on protein “makes no sense (Americans eat plenty) other than as an excuse to advise more meat and dairy, full fat, which will make it impossible to keep saturated fat to 10 per cent of calories or less.”

A White House official said the guidelines are based on sound science and are expected to support better public health outcomes as they are implemented across federal programmes.

What this means for the food industry

The new guidelines have placed increased pressure on major food and beverage companies, particularly those that sell sugary drinks, snacks, and processed foods.

Soda makers such as Coca-Cola and PepsiCo, as well as snack producers like Mondelez — which manufactures Oreo cookies — have faced scrutiny from Kennedy. European-based food giants Nestlé and Danone are also affected by the policy shift.

The American Beverage Association responded by noting that nearly 60 per cent of beverages sold in the US contain no sugar. It argued that discouraging sugar-free beverages is “impractical and inherently contradictory.”

Despite the criticism, some manufacturers have begun adjusting product formulations to align with the administration’s emphasis on fewer artificial ingredients.

What next in the 'Maha' agenda

The dietary overhaul is part of the Trump administration’s broader “Make America Healthy Again” initiative, a social movement that backs Kennedy’s leadership at HHS.

The agenda also includes controversial measures such as curbing childhood vaccines and limiting access to unhealthy foods for people receiving food assistance.

Kennedy and US Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins had pledged to simplify the dietary guidelines and reduce what they described as the influence of food companies over federal nutrition advice.

The new dietary changes will affect school meals across the country. The School Nutrition Association said that school meals already include fruits, vegetables, and other healthy foods in line with existing federal standards.

However, the group added that schools need more funding and training to expand from-scratch cooking and further improve meal quality.

Kennedy has linked the new guidelines to the goal of reducing healthcare spending, an issue that is expected to feature prominently in the 2026 US midterm elections.

“The new guidelines recognise that whole nutrient-dense food is the most effective path to better health and lower healthcare costs,” he said.

Healthcare affordability is a key concern for Republicans, and the administration has framed the dietary overhaul as a preventive strategy that could reduce long-term medical expenses associated with chronic disease.

With inputs from agencies