What is the story about?

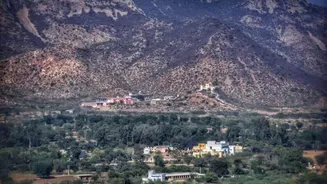

In a major turn in the ongoing Aravalli hills controversy, the Supreme Court of India on Monday decided to stay its own November 20 ruling that had limited what counts as part of the ancient Aravalli mountain range.

That earlier decision had drawn strong criticism from environmentalists, opposition parties and local groups for potentially opening up large swathes of the ecologically sensitive region to mining and development.

The court’s fresh order puts that November judgment “in abeyance” and signals a willingness to rethink how the Aravallis are defined and protected.

A three-judge bench led by Chief Justice of India Surya Kant, along with Justices JK Maheshwari and AG Masih, said the matter needs deeper examination before any final decision is made.

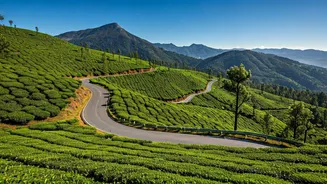

The original November ruling had accepted a technical definition – classifying only landforms rising 100 metres or more above surrounding terrain as part of the Aravalli Hills. Critics warned that this artificial height rule would exclude much of the natural, interconnected hill system that stretches over 700 kilometres across Gujarat, Rajasthan, Haryana and Delhi, potentially making most of the range available for mining.

During Monday’s hearing, the top court acknowledged that this simple elevation-based measure may not fully capture the ecological continuity of the range. Judges asked whether gaps between qualifying hills could still be part of a continuous ecosystem, and whether mining regulation should be tied strictly to height at all.

Rather than rush ahead with the earlier definition, the court proposed forming a high-powered expert committee made up of domain specialists to reassess how the Aravalli range should be mapped and regulated. The stay also puts on hold the government-led mapping exercise that had begun using the 100-metre criterion.

Solicitor General Tushar Mehta, representing the Union government, welcomed the suo motu review and said the earlier ruling had been misunderstood in some quarters. He also noted that public consultations are planned before any mining decisions are finalized.

The Supreme Court has scheduled the next hearing for January 21, 2026, leaving time for experts and stakeholders to weigh in on how best to balance environmental protection with development concerns.

That earlier decision had drawn strong criticism from environmentalists, opposition parties and local groups for potentially opening up large swathes of the ecologically sensitive region to mining and development.

The court’s fresh order puts that November judgment “in abeyance” and signals a willingness to rethink how the Aravallis are defined and protected.

A three-judge bench led by Chief Justice of India Surya Kant, along with Justices JK Maheshwari and AG Masih, said the matter needs deeper examination before any final decision is made.

Why the court took this step

The original November ruling had accepted a technical definition – classifying only landforms rising 100 metres or more above surrounding terrain as part of the Aravalli Hills. Critics warned that this artificial height rule would exclude much of the natural, interconnected hill system that stretches over 700 kilometres across Gujarat, Rajasthan, Haryana and Delhi, potentially making most of the range available for mining.

During Monday’s hearing, the top court acknowledged that this simple elevation-based measure may not fully capture the ecological continuity of the range. Judges asked whether gaps between qualifying hills could still be part of a continuous ecosystem, and whether mining regulation should be tied strictly to height at all.

What happens next

Rather than rush ahead with the earlier definition, the court proposed forming a high-powered expert committee made up of domain specialists to reassess how the Aravalli range should be mapped and regulated. The stay also puts on hold the government-led mapping exercise that had begun using the 100-metre criterion.

Solicitor General Tushar Mehta, representing the Union government, welcomed the suo motu review and said the earlier ruling had been misunderstood in some quarters. He also noted that public consultations are planned before any mining decisions are finalized.

The Supreme Court has scheduled the next hearing for January 21, 2026, leaving time for experts and stakeholders to weigh in on how best to balance environmental protection with development concerns.