There is a general air of uncertainty in international relations right now, and there is a distinct feeling that the old order changeth. The upheaval is likely to bring difficult times to all of us. The long-predicted end of the “liberal, rules-based international order” seems to be upon us, with a definite fin-de-siècle feeling. The certainties that we have long held on to are no longer reliable.

Foremost, of course, is the role of the United States, which bestrode the world like a colossus in the aftermath of the Second World War, and again after the end of the Cold War. Those of us born in the post-war years looked up to America, the “City on the Hill”, the beacon, celebrated in song and film, a cultural anchor in addition to a military and economic superpower.

I remember the day my dad walked into the dining room with his newspaper and told us, “Marilyn Monroe is dead.” I was a small boy, and I had no idea who Marilyn Monroe was, but I remember that moment. I vaguely remember the Kennedy assassination. And every month, SPAN magazine brought images of the good life. My father did his PhD on John Steinbeck.

Thus, for me, and for those of my generation, it was only natural to look up to the US as an exemplar. In college, we used to refer to it, only half-jokingly, as ‘God’s own country’. (This was before Amitabh Kant applied this moniker to Kerala, and it stuck.) I remember us reading Time and Newsweek in the IIT Madras hostel common room. We read them cover to cover.

So, it was but natural for us to write the GRE and apply to US universities; and many of us got in, with good scores and good grades. It was relatively easy in the late 1970s. And it was a revelation for us to go to a country that pretty much worked well; the standard of living was quite a bit higher than back at home, where you had to wait six years for a phone or a scooter.

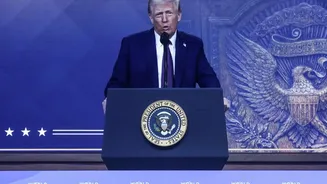

But fifty years later, things are not the same. The gap in the standard of living between India and the US has narrowed considerably, although the rule of law, clean air and public spaces, and the lack of petty corruption, plus the tendency to stick to the letter of agreements (OK, I grant that Trump may be an exception) are all still much more prevalent in the US.

What has happened, though, is the relative decline of the US in almost every way. Take research. Or manufacturing. Or popular culture. Others are narrowing the gap steadily. Or take the streets of, say, San Francisco. The pristine, well-kept streets I encountered when I first moved there are now in shambles, sometimes covered in human faeces, with homeless people and needles all over the place.

The US—and it hurts me to say this, as I am an unabashed Americophile (if that’s a word)—over-extended itself through unnecessary wars and unwise crusades which the Deep State promoted for self-preservation, but which in fact turned out to be counterproductive.

As I wrote recently in relation the Venezuela gamble, the US may well be following in the footsteps of other countries that once held the reserve currency, but fell into a trifecta of excessive debt, reduced core competence, complacency and overextension.

The resulting retreat into “Fortress America”, as outlined in the National Security Strategy, as well as the unabashed pursuit of American interests at the expense of allies and friends, is causing everything to fall apart, as in W. B. Yeats’s warning.

The reaction of the US’s closest allies to various Trump diktats has been instructive. Europeans and the British applauded when Trump chose to peremptorily remove President Maduro from Venezuela and make a play for that nation’s massive oil reserves. But when he began in earnest to pursue Greenland, there were loud protests from some parts of NATO.

That alliance appears to be crumbling as Trump, not unreasonably, suggests that Europeans need to pay for their own security, instead of expecting the US to finance it for ever. Also, despite the appearance of a land-grab, Greenland has a trade and security rationale: as the Arctic Sea becomes more ice-free due to climate change, the fabled Northwest Passage and other trade routes open up; China is already ready for its own land-grab with its “Polar Silk Road”.

Here’s a tweet from Ken Noriyasu of the Nikkei, highlighting future trade routes:

But the threat to Denmark’s territorial integrity, in case Greenland opts to join the US, has rattled NATO members. Threats of escalating tariffs (10–25 per cent) on Denmark and other NATO allies have sparked outrage. Joint Nordic/European statements reaffirm sovereignty; US rhetoric treats it as a strategic necessity (Arctic resources, China/Russia competition). This treats allies as transactional subordinates, eroding NATO cohesion.

The end of NATO would be a seismic shift, but I have long argued that Western Europe should bury its hatchet with Russia, because their real long-term foe is China, which has its eye on Siberia on the one hand, and Europe’s entire industrial might on the other.

There is more: ongoing wars (Ukraine, Middle East), tariff wars, alliance strains, and a rising “spheres of influence” logic. Davos 2026 panels describe it as the “last-chance saloon” for the old order. UN Secretary-General Guterres warns leaders are “running roughshod over international law”. Think tanks (Brookings, Stimson) call it an interregnum: the liberal order is dying, no coherent replacement has emerged, and “monsters” fill the vacuum. Is “some rough beast” slouching towards Bethlehem to be born, as in the apocalyptic prophecy?

What will rise from the ruins of the old world order? We can only wonder, as there are several possible answers:

1. Transactionalist multipolarity. Great powers (US, China, India, EU/Russia bloc) negotiate deals based on leverage, not universal rules. Might means right, backed by economic coercion or force.

2. Fragmented regional orders. Spheres where dominant powers set norms (US in the Americas/Arctic, China in the Indo-Pacific, Russia near its borders, if there is a rapprochement with the EU). I have long predicted spheres of influence in the wake of what I see as a G2 condominium between the US and China.

3. No-rules world (worst case). Rising impunity, more unilateral interventions, eroded deterrence, potential for cascading crises. We are already beginning to see this with China’s unilateral land- and sea-grabs (e.g. the “nine-dash line”).

2025 was an annus horribilis. 2026 is shaping up to be worse. None of the above scenarios is good for India, especially as it is beginning to get its manufacturing in order, at what appears to be exactly the wrong time, as tariff wars abound.

By the looks of it, 2026 will be worse for all concerned. Centrifugal forces are going to tear up globalism, and a narrow nationalism may not bode well for anybody.

(The writer has been a conservative columnist for over 25 years. His academic interest is innovation. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect Firstpost’s views.)