What is the story about?

Bangladesh is witnessing a silent but profound transformation – one that could redefine its future for decades. Under the stewardship of Muhammad Yunus, Dhaka is steadily drifting into the strategic embrace of China, with Pakistan acting as both intermediary and enabler. What is being presented as “development cooperation” and “defence modernisation” increasingly resembles a calculated power trap.

The warning signs are no longer subtle. US Ambassador Brent Christensen’s recent remarks about the risks of Chinese involvement struck a nerve not just in Beijing but in Dhaka as well. His comments came amid growing evidence that the Yunus administration is accelerating defence and infrastructure deals with China at an unprecedented scale.

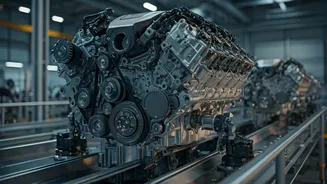

At the heart of this shift lies military cooperation. Bangladesh is exploring the acquisition of Chinese J-10C fighter jets while simultaneously negotiating with Pakistan for the JF-17 Thunder – another Chinese-backed platform. These are not short-term purchases. Such systems require long-term maintenance, training, software upgrades, and logistical support, effectively binding Bangladesh to Chinese and Pakistani defence ecosystems for generations.

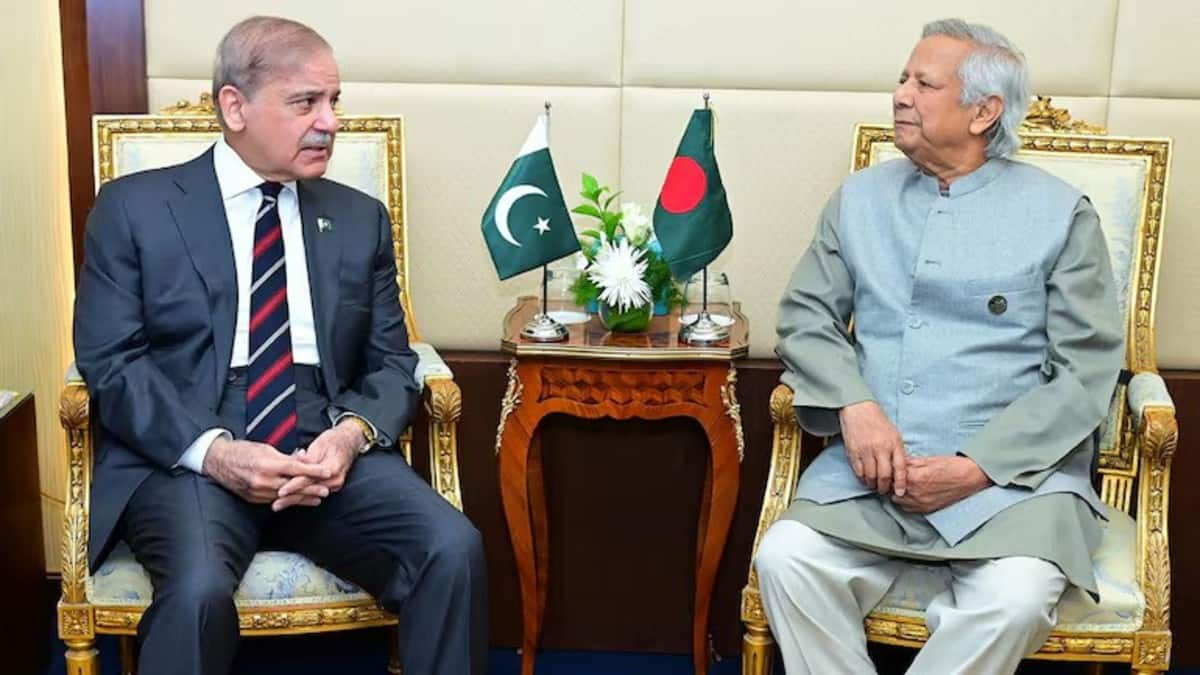

Pakistan’s military has not attempted to hide these engagements. In official statements, Islamabad confirmed that Air Chief Marshal Zaheer Ahmed Baber Sidhu held detailed discussions with his Bangladeshi counterpart, Hasan Mahmood Khan, on expanding defence cooperation. These talks reportedly covered the potential sale of JF-17 jets as well as the fast-tracked delivery of Super Mushshak trainer aircraft, accompanied by a comprehensive training and long-term maintenance package.

Pakistan has openly marketed itself as a gateway for Chinese military hardware. Talks between the air force chiefs of Bangladesh and Pakistan have already covered not only fighter jets but also Super Mushshak trainer aircraft, along with a promise of fast delivery and embedded training structures. This is strategic dependency by design.

Pakistan has also assured Bangladesh of the "fast-tracked delivery of Super Mushshak trainer aircraft, along with a complete training and long-term support ecosystem".

Meanwhile, China’s ambitions extend well beyond the military domain. The proposed Teesta River Master Plan, which Beijing wants to commence immediately, has raised alarm due to its scale, opacity, and strategic geography. The fact that this proposal was announced near the Siliguri Corridor, in the presence of Chinese Ambassador Yao Wen, underscores China’s intent to entrench itself in sensitive border-adjacent regions.

Meanwhile, Beijing harshly reacted to China-related remarks by the US Ambassador to Bangladesh on January 22, urging the US side "to be more aware of its responsibilities and focus more on actions" that are "conducive to Bangladesh's stability" as well as the development and cooperation in the region.

A spokesperson at the Chinese Embassy in Bangladesh, referring to Ambassador Christensen’s comments, stated, “Such remarks by the US Ambassador to Bangladesh are irresponsible and utterly unfounded.”

The spokesperson said they confuse right and wrong and are 'completely out of ulterior motives'.

The Chinese Embassy’s unusually aggressive response to Ambassador Christensen’s comments revealed more than indignation – it exposed anxiety. When a foreign mission reacts with such hostility, it often signals that something important is at stake. In this case, it is Beijing’s rapidly expanding influence over Bangladesh’s strategic decision-making.

During his confirmation hearing before the US Senate, Ambassador Christensen acknowledged precisely these risks. Responding to Senator Pete Ricketts’s warning that the sale of Chinese fighter jets would bind Bangladesh to Beijing’s defence industry for decades, Christensen agreed that such a move would carry lasting strategic consequences. He pledged that, if confirmed, he would clearly articulate the dangers of Chinese military dependency while also highlighting the tangible benefits of closer military-to-military cooperation with the United States.

The timing is critical. Yunus is pushing for a February 12 referendum alongside national elections, a move widely seen as an attempt to legitimise and consolidate his authority. Once cemented, this political control could allow him to pursue deeper alignment with China and Pakistan without meaningful domestic resistance.

Washington, for its part, faces an uphill battle. Yunus’s long-known hostility toward Donald Trump and his close ties with the Clinton and Soros networks complicate any effort by the US to exert pressure or offer alternatives. Unlike previous Bangladeshi leaders who balanced relationships across power blocs, Yunus appears ideologically inclined toward distancing Dhaka from a Trump-influenced Washington.

The danger lies not only in foreign influence but also in the erosion of strategic autonomy. Countries that enter Chinese defence and infrastructure arrangements often discover too late that exit costs are prohibitive. Debt, dependence, and diplomatic alignment follow almost inevitably.

Bangladesh risks becoming another case study – a nation that traded long-term sovereignty for short-term political consolidation. The Sino-Pakistani axis does not merely sell weapons or build dams; it exports a model of control, leverage, and quiet coercion.

As the referendum approaches and agreements multiply, the question is no longer whether Bangladesh is drifting eastward, but whether it will soon be unable to turn back. History shows that such alignments rarely end on favourable terms for smaller states. If this trajectory continues, Muhammad Yunus may succeed in consolidating his power – but at the cost of Bangladesh’s independent future.

(Salah Uddin Shoaib Choudhury is an award-winning journalist, writer, and Editor of the newspaper Blitz. He specialises in counterterrorism and regional geopolitics. Follow him on X: @Salah_Shoaib. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect Firstpost’s views.)

The warning signs are no longer subtle. US Ambassador Brent Christensen’s recent remarks about the risks of Chinese involvement struck a nerve not just in Beijing but in Dhaka as well. His comments came amid growing evidence that the Yunus administration is accelerating defence and infrastructure deals with China at an unprecedented scale.

At the heart of this shift lies military cooperation. Bangladesh is exploring the acquisition of Chinese J-10C fighter jets while simultaneously negotiating with Pakistan for the JF-17 Thunder – another Chinese-backed platform. These are not short-term purchases. Such systems require long-term maintenance, training, software upgrades, and logistical support, effectively binding Bangladesh to Chinese and Pakistani defence ecosystems for generations.

Pakistan’s military has not attempted to hide these engagements. In official statements, Islamabad confirmed that Air Chief Marshal Zaheer Ahmed Baber Sidhu held detailed discussions with his Bangladeshi counterpart, Hasan Mahmood Khan, on expanding defence cooperation. These talks reportedly covered the potential sale of JF-17 jets as well as the fast-tracked delivery of Super Mushshak trainer aircraft, accompanied by a comprehensive training and long-term maintenance package.

Pakistan has openly marketed itself as a gateway for Chinese military hardware. Talks between the air force chiefs of Bangladesh and Pakistan have already covered not only fighter jets but also Super Mushshak trainer aircraft, along with a promise of fast delivery and embedded training structures. This is strategic dependency by design.

Pakistan has also assured Bangladesh of the "fast-tracked delivery of Super Mushshak trainer aircraft, along with a complete training and long-term support ecosystem".

Meanwhile, China’s ambitions extend well beyond the military domain. The proposed Teesta River Master Plan, which Beijing wants to commence immediately, has raised alarm due to its scale, opacity, and strategic geography. The fact that this proposal was announced near the Siliguri Corridor, in the presence of Chinese Ambassador Yao Wen, underscores China’s intent to entrench itself in sensitive border-adjacent regions.

Meanwhile, Beijing harshly reacted to China-related remarks by the US Ambassador to Bangladesh on January 22, urging the US side "to be more aware of its responsibilities and focus more on actions" that are "conducive to Bangladesh's stability" as well as the development and cooperation in the region.

A spokesperson at the Chinese Embassy in Bangladesh, referring to Ambassador Christensen’s comments, stated, “Such remarks by the US Ambassador to Bangladesh are irresponsible and utterly unfounded.”

The spokesperson said they confuse right and wrong and are 'completely out of ulterior motives'.

The Chinese Embassy’s unusually aggressive response to Ambassador Christensen’s comments revealed more than indignation – it exposed anxiety. When a foreign mission reacts with such hostility, it often signals that something important is at stake. In this case, it is Beijing’s rapidly expanding influence over Bangladesh’s strategic decision-making.

During his confirmation hearing before the US Senate, Ambassador Christensen acknowledged precisely these risks. Responding to Senator Pete Ricketts’s warning that the sale of Chinese fighter jets would bind Bangladesh to Beijing’s defence industry for decades, Christensen agreed that such a move would carry lasting strategic consequences. He pledged that, if confirmed, he would clearly articulate the dangers of Chinese military dependency while also highlighting the tangible benefits of closer military-to-military cooperation with the United States.

The timing is critical. Yunus is pushing for a February 12 referendum alongside national elections, a move widely seen as an attempt to legitimise and consolidate his authority. Once cemented, this political control could allow him to pursue deeper alignment with China and Pakistan without meaningful domestic resistance.

Washington, for its part, faces an uphill battle. Yunus’s long-known hostility toward Donald Trump and his close ties with the Clinton and Soros networks complicate any effort by the US to exert pressure or offer alternatives. Unlike previous Bangladeshi leaders who balanced relationships across power blocs, Yunus appears ideologically inclined toward distancing Dhaka from a Trump-influenced Washington.

The danger lies not only in foreign influence but also in the erosion of strategic autonomy. Countries that enter Chinese defence and infrastructure arrangements often discover too late that exit costs are prohibitive. Debt, dependence, and diplomatic alignment follow almost inevitably.

Bangladesh risks becoming another case study – a nation that traded long-term sovereignty for short-term political consolidation. The Sino-Pakistani axis does not merely sell weapons or build dams; it exports a model of control, leverage, and quiet coercion.

As the referendum approaches and agreements multiply, the question is no longer whether Bangladesh is drifting eastward, but whether it will soon be unable to turn back. History shows that such alignments rarely end on favourable terms for smaller states. If this trajectory continues, Muhammad Yunus may succeed in consolidating his power – but at the cost of Bangladesh’s independent future.

(Salah Uddin Shoaib Choudhury is an award-winning journalist, writer, and Editor of the newspaper Blitz. He specialises in counterterrorism and regional geopolitics. Follow him on X: @Salah_Shoaib. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect Firstpost’s views.)