When does something become so important that it gets the same value as of a human? While there is no one answer, as that 'something' is subjective to everyone.

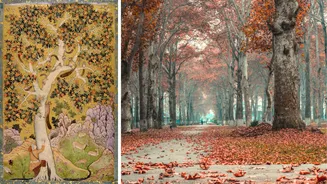

However, for the people of Kashmir, the answer lies in the trees of Chinar. It has received a 'Digital Tree Aadhaar'. The tree is what makes Kashmir, Kashmir. Whether it is the long history the region had with its trees, or how people not from the land may have romanticised it with. Chinar, has long been the cultural heritage of the region, and so its importance is such, that an identity card is extended to the trees too, to ensure, its rights are protected. The 'Aadhaar' comes with a QR code, which provides all information anyone would need, including the tree's location, status, growth, and its health. This will help the researchers to track changes over time and protect the region's cultural heritage.

The Long History Of Kashmir's Chinar, That Makes It Almost Human-Like

Reyan Ahmad in 'If the Chinars Could Speak', writes, "In Kashmir, the Chinar is more than a tree". He writes that it is a tree of memory, that witnessed how Kashmir "lived, loved, resisted, and suffered".

The Chinars saw the Mughals, heard Habba Khatoon's lament echo for her beloved Yusuf Shah Chak, and listened to the voices of Lal Ded and Nund Rishi, when Bhakti was at its peak.

For Kashmiri, it is Bouin. The tree is huge, and is part of the Platanaceae family. It grows up to 30 meters or more, with a girth that exceeds 150 meters. It has close to 700 years of life. It is right to say, that Chinars in Kashmir, are the wisest, the oldest, and one who experienced and remembered everything.

Chinar gets its name from the Persian word, which means "what a fire". The story has it that its crimson red colour gave it the name it bears, during the Mughal era. This is when a person saw the colour and yelled 'Chi-nar', or "what a fire". Some also believe that the words were actually 'Che-Naar-Ast?', or "what flame is it?" The name is believed to be given by the Mughal emperor Jahangir.

How Chinar Reached Kashmir

Historically, the tree is associated with Greece as its place of origin. It is known as the Tree of Hippocrates, as it was under this tree, where teachers in the history of medicine used to teach.

So, how did it reach Kashmir? While the answer to this still remains in the mystery, some historians trace its arrival to the time of the great empires that bridged Persia and the Himalayas. As in Persia, the Chinar tree was part of the city's life

However, others believe that Chinar has always been native to the land. In fact, its very name - Bouin, is believed to be derived from Goddess Bhawani, deeply embedded in Hindu mythology. This is why many Kashmiri Pandits view this tree not as foreign visitor, but a sacred presence.

There are older whispers, including the archaeological excavations as Burzahom, a Neolithic site that dates back to 3,000 to 2,000 BC. The site revealed traces of charcoal, which is believed to have come from the Chinar wood.

The puzzle yet deepens, because in one of the most well-documented texts from Kashmir - Rajatarangini, by Pandit Kalhana, written in 1148 CE, there is no mention of Chinar. However, some scholars do wonder if the Vata tree in his text referred to Chinar.

The general idea is that it was brought from Iran to Kashmir, when Syed Qasim Shah Hamdani, who accompanied Mir Syed Ali Hamdani from Iran, planted it in the land, near the mosque of Chattergam Chadoora, more than 600 years before. The proof of the tree still exists.

The Mughal emperor Akbar to is said to have planted around 1,200 trees after he took over Kashmir in 1586. The four Chinar island in the Dal Lake Char Chinari and Ropa Lank too were constructed during the Mughal reign.

Its bright red colour, to mauve, amber and yellow is what identifies Kashmir through its various season. As harsh as Kashmir's winters the tree too becomes lifeless. The tree is an inseparable part of Kashmir. It is in its history, religion, literature, and even politics. The heart of Kashmir's art is also through the tree especially the papier-mâché, pottery, shawl embroidery, silverware and carpet making.

As Ahmad also writes, the tree has drank people's grief in its root, and the leaves also rustled with every gunshot, it ever heard. The tree reminds the people of Kashmir of the phase of life, and beauty that always awaits, no matter how long the period of sadness maybe.

In fact, artist Megha Sindwani, who also once held a photo exhibition on Chinar, said, "The Chinar is not just resilient but also adaptable, making it a powerful metaphor for the people of Kashmir. It reflects their occupations, traditions, and enduring hospitality. For me, the Chinar represents a bridge between permanence and change, beauty and struggle. Much like the region itself, the tree holds stories of survival and strength."

In fact, one of her captions that used Chinar as the metaphor with the lives of those in Kashmir, displayed in the exhibition read:

"Fragile and worn, a Chinar leaf rises against the sky, as if resisting the pull of the earth. In Kashmir, as in life, even what falls refuses to be forgotten."