If the season ended right now, the Bears would make the playoffs for the first time since 2018. However, something else interesting would happen for the first time in even longer. The Bears would draft in the second half of the first round. The last time that happened, 2013, Phil Emery picked Kyle Long at #20. Star Wars only had six movies back then, the “new” Superman was Henry Cavill, and all of the Stark children were still alive. Caleb Williams was eleven.

It’s been a minute.

Since then, in the first round Chicago has drafted 14th, 7th, 9th, 2nd, 8th, 11th, 10th, 1st, 9th, and 10th. They have also missed having picks in the first round on three occasions due to various trades.

If the scope of how unfamiliar this territory would be for Chicago fans is still unclear, it’s worth pointing out that Gabe Carimi is one of only two players the Bears have drafted in the first round after a playoff run since losing to Peyton Manning in the Super Bowl, and the other is Justin Fields–who was drafted after an 8-8 season but only after Chicago traded up to #11.

Consequently, it’s worth exploring what exactly draft picks look like in the later stages of Day One.

Overview of Late 1st-round Picks

In the fifteen years since the modern CBA went into effect, the players taken 21-32 in the first round include 33 offensive linemen, 28 edge defenders, 27 cornerbacks, 26 wide receivers, 17 interior defensive linemen, and 15 off-ball linebackers–plus smaller samples of the other roles. However, those six positions are the ones that average at least one selection per year. The split skews about 55% toward the defense, and three teams (the Ravens, the Packers, and the Vikings) are tied at first for having made 13 selections each in this range.

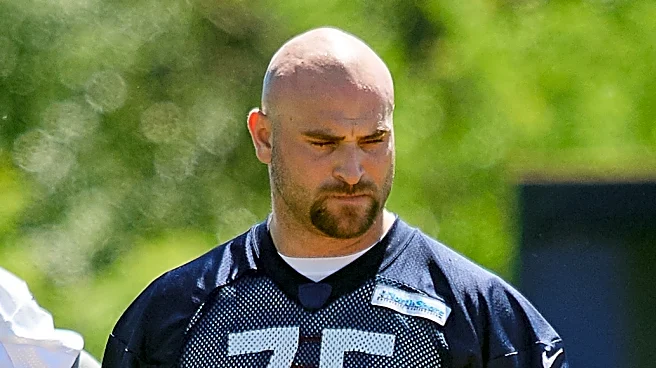

Offensive Linemen

Of the 22 offensive linemen in the Draft Research Project who were taken in the first round but after #20, more than half played a substantial portion of their snaps at tackle, and the median player in this group started 63 games of the first 80 that were available. Only two of these players made the Pro Bowl in their first five years, but the rest didn’t just make rosters. They played, and they played a lot.

This seems to be where high-performing teams find reliable help up front. It is not true that only a guard will be found here. Instead, it’s true that offensive linemen found here will likely be able to play up and down the line.

Edge Defenders

A median-level performer for edge defenders in this group found in the Draft Research Project (n=14) would play in 63 games but only start 25 of them. His average season in his first five years in the league would see a single defended pass, 3.5 sacks, and 5 TFLs. Think of a slightly less productive Nick Perry or a slightly more productive Charles Harris, not Leonard Floyd (whose four years in Chicago would be a pretty close match to this player’s first five years in the league in terms of production). Better edge defenders can be found in this stage, but it would likely take multiple attempts in this stage of the draft or in the second round to find a true impact player.

Of note, the best three in terms of production–T.J. Watt, Montez Sweat, and Cam Jordan–were all considered in draft profiles to be minor projects who would need time to adjust and develop. Drafting at this stage seems to involve being willing to make at least one compromise.

Corners

The median cornerback, meanwhile (n=16) would play in just 58 games with 27 starts. He would deliver less than one interception per year while defending four passes a season. He might average one tackle for a loss each year. In fact, the median second-round corner will outperform the median corner from this group, and when some snapshots suggest that there is not a lot of difference between 1st- and 2nd-round corners, the relative underperformance of the second half of the first round is why. Obviously, in real life anything can happen and quality corners can fall to the bottom of the first round. However, it’s probably more reasonable to wait until the second round.

Wide receivers

No. I can’t pretend that it makes sense for Chicago to draft a wide receiver at this point, so this section is instead going to be devoted to safeties, who don’t typically get drafted in the second half of the first round. There’s a reason for that.

Admittedly, the Bears might be needing to replace safety Jaquan Brisker, who has produced 4 interceptions, 16 pass deflections, 7 sacks, and 12 TFLs in four years while starting 45 games in just over 3.5 seasons. Meanwhile, a late first-round safety would have 7 interceptions, 26 PDs, 3.5 sacks, and 10 TFLs; scaled down to adjust the playing time Brisker has remaining in his first five years, that would be 5 interceptions, 19 PDs, 2.5 sacks, and 9 TFLs. That’s slightly more ball production but notably less in the way of plays that disrupt behind the line of scrimmage.

Given the ability to find decent to plus safeties later in the draft, it might actually make more sense for the Bears to consider a wide receiver. Okay, not really.

Interior defensive linemen

A Bears fan who has been watching Gervon Dexter for his last 42 games and has thought “could we find someone like that, only who played less and had fewer sacks?” would be delighted by the median interior defensive lineman drafted 21-32 (n=12). This player would probably play each of his first five seasons, averaging 15 games and 8 starts, with just under 2 sacks per year and only 3 TFLs per season. That’s fewer games and starts than Dexter is on track to produce, and less than half as many sacks per season as he has been averaging. The best outliers to this in terms of production were all drafted to teams with defenses in the top quartile, already.

Off-ball linebackers

Fans should temper expectations for off-ball linebackers taken late in the first round (n=12). They tend to have adequate playing time (over sixty games and starts), but the median such player only produces a single interception, defends 12 passes, manages 9 sacks, and 29 TFLs. That’s three fewer defended passes but a couple more sacks over the first five years than the median second-round linebacker. In other words, while it is certainly possible to come up with a scenario where an off-ball linebacker makes sense at this point, it’s not likely to be the best use of the draft capital with the exception of a caveat mentioned below.

Reflections

So is that it? The Bears won’t be able to find a difference-maker? Not exactly. In general, the end of the first round behaves more like the second round than it does the first 10-12 spots in the draft. However, while there are draft classes where there are not more than one or two true “standout” stars found in the later stages of the first round, more often than not there are three or four players taken in the first round who are at the top of their position over the next five years. After all, good teams often manage to stay good.

The secret is not likely to be “positional draft order”, either, because the top-producing linebackers, interior defensive linemen, and corners are actually sometimes the third, fourth, or fifth at their position on the board. The same is true of edge rusher (and remains more or less true even when separated out by 3-4 OLB and 4-3 DE). Put simply, it is possible to make strong-ish statements about what rebuilding teams should do in the draft, because when teams have a variety of needs, it is easier to leverage positional value and need.

By contrast, teams that find themselves drafting outside of the first half of the first round seem to need to adopt one of two strategies. The first is to simply do what most front office executives insist is the plan all along–they need to draft the best player available and take advantage of talent that falls to them, regardless of position. That might be an off-ball linebacker or a safety, but most of the time it will not be. The second is to target a position and accept that in doing so they are often getting talent comparable to what will be available 20 or 30 spots later. Of course, for teams that already have competitive rosters, both of these choices are reasonable.

It’s a good problem to (potentially) have.