The more I research this topic, the more amazed I am at how many good hitting seasons there have been. Hitting a baseball that is traveling at 90 mph with a piece of wood remains one of the most difficult

things to accomplish in sports. Hitting a baseball is also one of the most enjoyable things in sports. I used to carry a bat in my trunk just in case I passed through a town that had a batting cage. You don’t find those around as much as you used to, but I’ve fed quarters and tokens into cages across this great country for nothing more than the pleasure of hearing and feeling that familiar sound of bat hitting ball. And much like my baseball idol, George Brett, I never wore batting gloves. I wanted to own my calluses. As I’ve gotten older, going to the cage is one of the things I really miss.

A side note about a great hitter of our time. A couple of weeks ago my oldest son, daughter-in-law and grandson went to see the Rockies and Angels play. They had great seats, in the second row behind home plate. Before the game, we texted and I told him that he might get to see Mike Trout play and to remember this night, as Trout will be a first ballot Hall of Famer. As luck would have it, Trout was the DH that night. In the eighth inning, he smashed a ball deep over the centerfield wall, 485 feet to be exact, for career home run number 400. What a lucky occurrence!

James grew up around the game (with me as dad, how could he not), and as he’s gotten older he’s developed a love of the game, and it’s nice to see him pass that through to his son. Plus, they got their faces on the Trout video, forever etched into eternity. James and his brother also happened to be in the stadium one night several years ago when Yasiel Puig, playing for the Dodgers, unleashed a monster throw from right field to cut down a runner at third. They both texted me immediately afterwards, still in a state of shock and awe, over the throw. I told them to remember that moment. They’ll go to games for the next fifty years and never see that play again.

Baseball always delivers a memory.

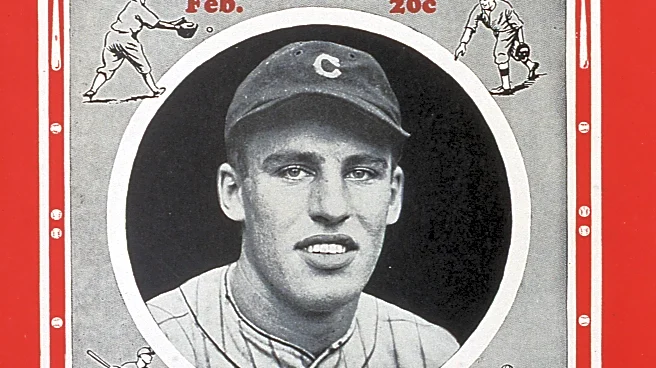

Young James Foxx was an athletic marvel at Sudlersville (MD.) High School. Built like a fireplug, he was an outstanding baseball, soccer and track athlete and for a time, held the state record in the 80 and 220 yard dashes. This was back in the days before track went to the metric system.

Connie Mack signed young Foxx, now known as Jimmie, before he graduated from high school. That’s how promising he was. Mack gave Foxx a little bit of action in 1925 and 1926, which were his age 17 and 18 seasons. Foxx spent most of those two years, plus half of 1927 in the minors, honing his prodigious hitting abilities.

Mack finally turned the kid loose in 1928, and Foxx quickly developed into one of the game’s best hitters. Foxx, like many of the all-time greats, had a very long peak. His stretched from 1927 to 1940. It’s tough to pin down his very best season, but 1932 had to rank near the top. With the country reeling from the Great Depression, Foxx gave fans in Philadelphia something to cheer about.

Foxx was a menace all summer, hitting .364 and leading the league in at least five statistical categories while winning his first MVP award.

Over 154 games, Foxx stroked 213 hits, which included 33 doubles and 58 home runs. He scored 151 times and drove home 169 more while racking up 438 total bases. The total base number is still the fifth-highest total ever. Foxx hit his peak in an 18-inning game at Cleveland on July 10. He came to the plate ten times and collected six hits, including three home runs and a double. His 8 RBIs and 16 total bases helped lead the Athletics to a wild 18 to 17 victory.

Foxx spent 12 seasons in Philadelphia, seven more in Boston, and two with the Chicago Cubs, before calling it a career at the age of 37. He retired with 534 career home runs and a .325 batting average. He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1951 on his seventh ballot. Think about how crazy that was. Foxx was a nine-time All-Star and won two World Series titles. He won the MVP award three times and was the Triple Crown winner in 1933. And the writers of the day didn’t put him in on the first ballot. In fact, he only got 13% of the vote on his first ballot. The equivalent would be making someone like Albert Pujols go through seven votes before induction. Things were different in the old days.

In retirement, Foxx did some coaching, including a stint as the manager of the Fort Wayne Daisies of the All-American Girls Professional League. The Jimmy Dugan character in the movie, A League of Their Own, is loosely based on Foxx. Like many of the great hitters of his era, Foxx died young, at age 59, after choking on a piece of food.

One of my favorite stories about long-forgotten ball players is that of one Hal Trotsky. Trotsky and I share the same birth date, which is a bonus. Trotsky was born and raised in Norway, Iowa, a small burg of about 500 souls situated about 17 miles southwest of Cedar Rapids. On the village’s Wikipedia page, it lists three Notable people: Trotsky, Bruce Kimm, who was a catcher with Detroit and both Chicago teams for a few seasons, and former Royal Mike Boddicker. That’s an impressive output for a town of its size. Norway was also known throughout the state for its top-notch high school baseball program and even had a movie made of its demise, called appropriately, “The Final Season”. Norway still embraces its baseball heritage.

Boddicker pitched for four teams over an excellent 14-year career. Nine of those seasons were spent with the Orioles where he had a solid peak from 1983 to 1986. He was the MVP of the 1983 ALCS, the last year in which the Birds won a World Series.

Trotsky was arguably a bigger star than Boddicker. Trotsky was signed by the Cleveland Indians at the age of 18. He split the 1931 season between two Class D teams in Cedar Rapids and Dubuque. By 1932 it was becoming apparent that he was a hitting prodigy. He saw action at three levels in 1932 before spending most of 1933 at AA Toledo. The Indians gave him an 11-game cup of coffee at the end of the 1933 season, in which he hit .295.

He made the Indians for good in 1934 and was outstanding, hitting .330 with a then-rookie record of 374 total bases. He had an excellent seven-year peak between 1934 and 1940 despite being hampered by debilitating migraine headaches.

His best season might have been 1936, though he was pretty darn good in 1934, 1937 and 1939 too. Before being waylaid by migraines, Trotsky was a total base machine. Between 1934 and 1937, he averaged 372 total bases per season. For perspective, Bobby Witt Jr. set the Royals season record for total bases in 2024 with 374. Trotsky nearly averaged that number for four consecutive seasons. The guy could flat out hit.

He appeared in 151 games in 1936, hitting a career best .343 with 42 home runs and a league-leading 162 RBI. He recorded 216 hits, which included 45 doubles and nine triples. He didn’t walk much, just 36 times but he only struck out 58 times, which is minuscule by today’s standards. What he did was hit, and hit for power, especially with men on base. He recorded 405 total bases in 1936, which also led the league. For all that offensive output, he only finished 10th in the American League MVP race, which was won by Lou Gehrig, who was his usual outstanding self, hitting .354 and leading the league in runs scored, home runs, walks, and slugging percentage. Trotsky’s RBI total was the Indians single single-season record for 63 years, before being eclipsed by Manny Ramirez’s 165 in 1999. The 405 total bases are still a franchise record.

Trotsky was a model of consistency all summer. His best game came late in the season, when on September 13th he led the Tribe to a 13 to 2 stomping of the Boston Red Sox at League Park. Trotsky went four for four with two home runs and a double. He drove home seven runs and collected 11 total bases. He also recorded 11 putouts from his first base position.

Trotsky’s story is one of tragedy. Starting in 1938, he started experiencing almost continuous migraines, which affected his vision. He was deemed unsuitable for World War II service due to his migraines, and after years of struggling and trying to find relief, he finally hung up his spikes in 1946 at the age of 33. In retirement, he did some coaching before getting into agricultural real estate sales. He died in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, on June 19th, 1979, at the young age of 66. His son, Hal Junior, had a very brief career with the Chicago White Sox in 1958.

Trotsky remains one of the great “what-ifs” of baseball history. I think he would have been a Hall of Famer had he not been waylaid by migraines.

Hank Greenberg was the first Jewish superstar in American sports. Known as the Hebrew Hammer, he was one of the game’s premier sluggers from 1933 to 1947. The Yankees tried to sign the Bronx native out of high school, but with Lou Gehrig entrenched at first base, Greenberg elected to attend college. He had a later tryout with the New York Giants, but Manager John McGraw was not impressed by the 6’4 youngster and passed on signing him. After his freshman year in college, the Tigers signed Greenberg for $9,000.

When World War II broke out, Greenberg was the first major league player to enlist and, by doing so, missed almost four complete seasons of his prime. His military service of 47 months was longer than any other major league player. Greenberg was often the target of antisemitic abuse and racial slurs in his career. Having endured his share of prejudice, Greenberg was one of the first and few opposing players to welcome Jackie Robinson to the majors.

Greenberg had a remarkable peak run of eight seasons between 1933 and 1941. He was still a feared hitter when he returned from the Eastern Theater. In fact, he hit 44 home runs and drove home 127 in his age 35 season (1946) but elected to retire at the age of 36 after the 1947 season in which he played for the Pirates, even though he hit 25 home runs and had an on-base percentage of .408.

He won two MVP awards, the first coming in 1935, when he led the league in home runs, RBI, and total bases. The second came in 1940, a year in which he led the league in doubles, home runs, RBIs, slugging percentag,e and total bases. He led the American League in home runs and RBIs four times, was a five-time All-Star, and led Detroit to two World Series titles.

Greenberg never really had a slump in 1940. His best series came late in the season, against the Philadelphia Athletics at Tiger Stadium. On September 18 and 19, the two teams played back-to-back double headers, and Greenberg absolutely destroyed Athletic pitchers. He came to the plate 19 times in those four games, collected seven hits and drew seven walks. He rolled up 22 total bases behind four home runs, a double, a triple, and a single. He drove home 12 runs while only striking out once.

In retirement, Greenberg joined the Cleveland Indians front office, eventually rising to the General Manager position. During his tenure, he signed more African American players than any other General Manager, though he did whiff on Henry Aaron, Ernie Banks, and Willie Mays after receiving unfavorable reports from his regional scouts. Imagine how good the Indians could have been with those three in the lineup!

After leaving baseball, Greenberg had a successful career as an investment banker and later in life became an avid tennis player. Despite his impressive career numbers, Greenberg was not elected to the Hall of Fame until his ninth ballot. The Tigers retired his number 5 in 1983. Greenberg passed away in September of 1986 after a year-long battle with cancer.