I’m looking for some self-belief, but my screentime’s up again this week

Father, can’t you help me?

Vincent Kompany’s Bayern Munich are one of the strongest teams in Europe, and one of the most dominating

presences the sport has ever witnessed, a testament to not only Kompany’s abilities as a coach but the team’s abilities to perform at a very high level, synergising with Kompany’s ideas about football.

However, despite all of this, Bayern walked away from the 2024/25 season with just one trophy: the Bundesliga. The DFB-Pokal eluded the team once again, the UEFA Champions League saw the team crash out due to a comeback from Internazionale, and the Club World Cup saw Bayern utterly dominate a game but fail to capitalise against a Paris Saint-Germain that looked far more vulnerable against them than they did against any other team in months prior. Much like Julian Nagelsmann’s Bayern of years prior, it seems the fundamentals are all in place, but some key pieces and details are still yet to be figured out, details which are so far the difference between Bayern finishing games and failing to reach a single tournament final since 2020 (the DFL-Supercups don’t count).

What could these changes be? How do the new signings fit into these new structures? Let’s look at it all.

Some assembly required: The structural requirements and adaptations

The general sat, and the lines on the map moved from side to side.

To know that every wave might not be the same, but it’s all a part of one big thing

Oh, it’s not just me, it’s not just me, it’s not just me, it’s everybody

First, we review the principles that Kompany wants to play with that I think work with this squad, and if we can evolve them.

Kompany’s Bayern play a high-intensity style that both presses all the way up the field and pushes the entire team up on the ball too, with a high line that goes even beyond the half-line in certain games. There is no compromise in terms of giving space to the opposition for a better defensive shape in most games, and the games where concessions are made are often the ones against high-profile opposition such as Paris Saint-Germain and Internazionale. On the ball, the team relies heavily on positional rotations and overloads, with most if not all players affecting play in all three phases of possession from the strikers to the centre-backs. These principles are landmarks of not just Kompany’s style of play but Bayern Munich’s footballing philosophy, and I think they are untouchable. If the team isn’t throwing the hammer down with a press to win the ball in the opposition’s defensive third and throwing bodies forward for a fifth goal, the team is not Bayern.

The Achilles’ heel of the Bayern team as of late has easily been the full-backs. While we possess a multitude of full-backs with differing profiles, Kompany has a very specific way of structuring the team which has limited his ability to rotate the players as much as he could. This has resulted in certain players playing in roles they are not comfortable in. The primary example of this is how the full-backs attack, which limits Kompany’s choices heavily, especially at right-back where Sacha Boey is the only real replacement for Konrad Laimer, despite his subpar performances as of late. We have seen Kompany adapt the left-back role for Josip Stanišić in the absence of Alphonso Davies, but I think further adaptation is required on both sides. In short, I think an intentional ambiguation of the role of full-backs in the final third would help Kompany rotate the players more often rather than forcing him to throw the same players into the same suboptimal situations simply because the alternatives are even worse for the hyper-specific role they play.

With all of this in mind, let’s look first at the formation and roles I am employing in this iteration of the Kompany system, and who I think is ideal for the roles (since the roles and structure have been tailored to the personnel we have at our disposal).

Casting call: The roles in play

“Listen son!” said the man with the gun, “There’s room for you inside.”

Bite the lightning and tell me how it tastes, kung fu fighting on your roller skates

Fill in a circular hole with a peg that’s square, but just don’t sit down ‘cause I’ve moved your chair

Our first role to discuss is one that we actually don’t need to discuss anything about. As of writing, it is 2025, and goalkeepers haven’t started dribbling up to the half-line and playing key passes into the box yet, but all it takes is one transformative figure and it could all change. Don’t believe me? Look at who we have in goal. While I am excited for Jonas Urbig’s future and he should definitely be taking the #1 spot in years to come, Manuel Neuer has proven after his recent performances that he is still sharp and an elite goalkeeper, even if he isn’t at the level he used to be.

Our starting centre-back pairing consists of Dayot Upamecano and Min-jae Kim. Jonathan Tah’s instant ascent to leadership status has been well-documented, but I think he’s simply not quick enough to work in this system as well as a fit Kim. However, Tah will no doubt get a comparable amount of minutes to the other two considering the amount of rotation required to keep a squad like this fresh in the modern football calendar. I think for any top team, three top-level CBs is a must and we have that now. Our starting right-back is Konrad Laimer who has shown that while his technical abilities may not be the sharpest, his understanding of what Kompany wants out of him and his sheer hard work more than make up for it, and in the process has quickly become my favourite player in this squad. The designated backup for him is Raphaël Guerreiro, a player whose limitations have become increasingly visible as his physicals seem to be evaporating, making him more suited to the right side in this system than the left, where he only really has one avenue to use his stronger left foot in. Our starting left-back would of course be Alphonso Davies in theory, but he is injured, as is his designated backup in Hiroki Itō, leaving us with Josip Stanišić starting there for now.

However, assuming a fully fit squad, Stanišić will take more of a free role in the squad, basically filling in the backline wherever required, whether it’s at CB, LB or RB. Itō is more than capable of filling in at CB as well, giving us a multitude of options. You will notice that I haven’t mentioned Sacha Boey here at all, and it’s because I believe he simply doesn’t have a place in this squad. I was a firm believer in his abilities last season, but his regression as a player since his injuries is clear and I believe any minutes given to him would be better served given to an academy player like Chivano Wijks or even Javi Fernández. If we get a fair market value offer for him in January, he should be out the door.

Kompany has employed the classic 4-2-3-1 as the on-paper starting formation, the defining feature of which is of course the double pivot. Kompany’s version of the 4-2-3-1 has often used the two pivots in symmetrical fashion, with both dropping into the defensive line at times and both pushing forward. However, I want to return to a system more akin to what Kompany did early on in his tenure, and has experimented with this season already in giving each pivot unique roles depending on the phase of play. These two roles I will name ‘Controller’ and ‘Destroyer’ respectively. The names aren’t indicative of exactly what they are, but it does give a general idea of the kind of role expected of each player. The Controller role is obviously going to be headed by Joshua Kimmich, with Aleksandar Pavlović as his deputy, and the Destroyer role is a free-for-all between Tom Bischof and Leon Goretzka.

The Controller is going to be our most important piece in build-up, the same way Kompany centres his build-up structure around Kimmich. They are the ones on the ball more than anyone else, and they are the ones who ultimately decide which angle the ball is going to progress from when it goes beyond the first line of the press. The Destroyer meanwhile, has little involvement in build-up, playing pretty much as a forward on the ball, but out of possession they are not only active in covering ground but the two profiles I’ve chosen for this role are specifically ones that either tenaciously and constantly take ground duels (Bischof) or are dominant in the air and physically (Goretzka).

In attack, our right-wing spot is already pretty clear. Michael Olise starts, with Lennart Karl as his deputy. On the left, Luis Díaz is the starter, with Serge Gnabry, Nicolas Jackson and even Wisdom Mike capable of filling in for him if required. Through the centre is where things get interesting, as under Kompany, the team seemed to function more with two strikers who both like to drop into midfield rather than a traditional 4-2-3-1. I will be keeping this part of the system, with one of the striker positions meant to be headed up by Jamal Musiala, but in his absence the spot will be shared by Nicolas Jackson and Serge Gnabry, with Olise, Díaz and Karl capable of filling in. Harry Kane of course takes the last spot in the XI, but Jackson, Gnabry and Díaz are all capable of playing that role too. As you can see, there is a lot of space for fluidity, but the champagne front four for now consists of Díaz, Olise, Jackson and Kane, and the system was crafted with these profiles being the primary ones in mind, although the way the profiles have been split, you can really go crazy with mixing and matching things, and it will still work on a fundamental level, although some of the finer details may not line up as cleanly.

Put pressure on the pinned piece: The out-of-possession adjustments

Black and blue, and who knows which is which, and who is who.

Sun, bring the sun

Sun, bring the sun

Sun, bring the sun

Sun, bring the sun

Sun, bring the sun

Sun, bring the sun

Sun, bring the sun

Sun, bring the sun

Kompany’s Bayern is, in theory, defensively the best team in Europe. However, the utilisation of Jonathan Tah instead of Min-jae Kim has hurt Bayern’s ability to defend counters massively. Tah should not be a starter until the return of Alphonso Davies, whose recovery pace will help Tah out on his side.

There is little else to change here, I think Bayern’s defensive issues are a result of injury problems rather than systemic deficiencies. The backline remains unchanged in their principles, to maintain a high line and for the CBs to have the freedom to go up the pitch to follow their man to further compact the opposition into their own block to create smaller areas to press in and win the ball back. I also think that Tah should be integrated into the team far slower than this, as he’s spent the last few years as part of a backline at Bayer Leverkusen that did not come forward much, being far more used to box defending as part of a block rather than having to guard larger areas on the break which is why he’s been caught out a couple times in the goals Bayern have conceded so far. A few months of grace period to adjust to the new system and demands is a must for any modern centre-back transfer, and Bayern’s situation is so wholly unique and extreme that we must cut even more slack for our CBs. I’m serious, guys, I’m sure the people on the Patreon’s Discord channel have probably been slagging off Upamecano and Kim for the last six months with no one left to defend them since I left, and it’s going to be no different with Tah.

Further up the field is where things get interesting, as Kompany has often employed a man-to-man system that pushes the entire team all the way up the field, pinning the opposition into their own half even when they have the ball, and utilising cover shadows to press players into smaller and smaller spaces before the overload of players wins the ball back through a loose touch being picked up or a long ball being gobbled up by the centre-backs before being sent to the keeper for recycling. We keep these principles, of course.

Note: It’s important to remember that these are general guidelines for the principles the tactics should operate on. Every match and team are different, that’s why every club has such extensive video and data analysis departments to break down how each team sets up and create counter-play. What is being showcased is more of a template than a one-size-fits-all solution to every problem Bayern will encounter over the course of this season.

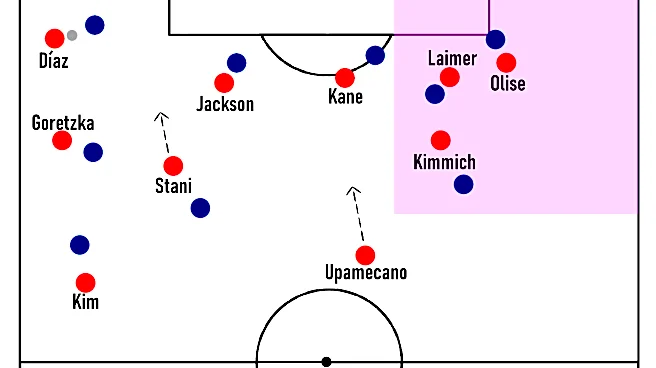

We start with how the team looks out-of-possession in the most general sense possible. Here, the opposition goalkeeper has the ball and the team is spread out over their own half, a situation that won’t be common but gives us the baseline for how this system works.

The team utilises a 4-4-2/4-2-4 shape, with both strikers and wingers tying down the defenders and forcing the keeper to play more directly. The backline tie down a player each, and have the license to roam to follow their man if required. However, the pivot is where it get interesting. The most logical response to this structure is either to push the team up and go long — which is playing right into Bayern’s hands with their aerial dominance — or pull a midfielder deep. When the latter occurs, Kimmich is tasked with following that player. If it’s the man Kimmich was marking, happy days. If it’s the other pivot, Kimmich is still the one who goes to mark that man while Goretzka shifts onto the midfielder that stayed advanced (slide 3).

This accomplishes multiple things.

One: Kimmich, if he wins the ball, can immediately launch a chance-creating pass with his passing ability.

Two: Goretzka hangs back, creating an area in front of the defense — where the long ball is likely to be sent — where Bayern have their three best aerial players concentrated, essentially guaranteeing a turnover if the keeper goes long (slide 2).

Three: If the ball is won but there is no direct way in, rather than Goretzka winning the ball and having to play rest passes or wait for the rest of the team to come forward, Kimmich winning the ball results in Goretzka immediately having the ability to overload the opposition defense with a box-crash on top of the already advancing attackers. This might seem counter-intuitive as Kimmich can do the same from deep, but not only does that put Kimmich and Goretzka in the opposite roles to what they’re used to (Kimmich as the box-crasher, Goretzka as the ball-player), it messes up the build-up and attacking patterns that the team already have in mind if Kimmich is on the opposition’s last line and Goretzka is in the controller position.

Against teams that manage to keep Bayern spread out, we sacrifice our immediate pressing threat by dropping Jackson into midfield. This means that the opposition centre-backs have a 2v1 againsts Kane, but we trade this off for a numerical advantage of our own at the backline, with the two centre-backs having just one striker between them. If the opposition employ a two-striker system, we drop Goretzka back to maintain the numerical advantage and adjust markers accordingly in midfield and out wide.

The numerical advantage in their third is utilised to bait the opposition into a pass across their defense, which triggers the press. Kane closes down while cutting off the passing lane to the other centre-back, while the whole rest of the team steps up to compress the opposition, and Jackson joins Kane in pressing while keeping the opposition’s defensive midfielder in his cover shadow. Notably, Kimmich will leave his man to step up, ready to infiltrate the free right half-space and link up with Olise should the ball fall to him, but this momentarily removes our numerical advantage in defense as Upamecano is now tasked with dealing with the free man. The ball over to the far side is almost impossible to nail, however, so it’s not as big of a risk as it may seem. If the pass is too high, Kimmich has time to scamper back while if the ball pass too flat, it would need to be ridiculously precise to get between Jackson, Goretzka, Kimmich and Upamecano.

All other details of this system are reliant almost completely on opposition formation and profiles, so this is as deep as we can go with the out-of-possession system without needing to add a million asterisks to everything. Let’s move on to how we do damage with the ball.

Opening theory: The build-up foundations

With, without, and who’ll deny, it’s what the fighting’s all about.

All in all, it was just a brick in the wall

All in all, it was all just bricks in the wall

Once again, we keep the fundamentals of what makes Kompany’s Bayern tick on the ball. And by what makes Kompany’s Bayern tick, I am obviously referring to the one-man metronome that is Joshua Kimmich.

Kimmich’s drops into the defensive line while the full-backs push up has been the most consistent feature of Kompany’s Bayern in possession, and it will form the crux of this shape too. There are, however, key differences that showcase the evolution of the full-backs to better cover up for technical and physical deficits in the current crop of players we have available at those positions, changes which of course reverberate across the rest of the structure.

Our biggest change is changing the make-up of the pivot. Rather than pushing Laimer up the field early and putting Goretzka in the pivot, we swap their build-up roles. Laimer becomes part of the pivot alongside Stanišić, meaning the pivot consists of both full-backs inverting. Goretzka, meanwhile, becomes part of the last-line attackers, occupying one of the defenders while Jackson is a step deeper, attracting the defensive midfielder. This one change not only makes defensive transitions far easier on the full-backs but also utilises Goretzka’s ability to dominate in the air as not just a box-crashing late runner but as a fixture of the attacking constellation.

Here we see a basic application of the first structure, used against teams that press with a three-man frontline.

Stanišić drops between the lines while Kim pushes wide, forcing the opposition winger to commit to one player. If the winger commits to Kim, the lane to Stanišić is open, who can lay it off first-time before getting muscled and advance the ball. If the player commits to cutting the lane to Stanišić off, all hell breaks loose after the ball comes to Kim as suddenly Stanišić has three opposition players in his area, meaning there is acres of space for others to run into. Goretzka is the first to take advantage, dropping into the vacant space opened by Stanišić. Goretzka’s marker can either leave Goretzka free to receive the ball or can chase him which will result in further disaster as suddenly a massive space opens up behind him that Díaz, Jackson, Laimer and Kane can all run into. Kim can play that ball consistently too as he can easily open his body up to his stronger right foot in this situation and zip it through rather than having to rush a pass on his left, although even if he is pressed tight, a left foot wrap around the presser to Goretzka is still realistically possible.

The mirror image of this works too, as Kimmich is more comfortable making that pass on the in-step with his right foot instead of opening his body up, and of course the wrap-around will be on his stronger foot too.

What’s important to note is how the pivot interact with each other. When one of the back-three push wide, the near-side pivot is the one that drops in while the other one pushes up to ready themselves to attack the space in behind.

If the wide defender isn’t pressed, they can simply carry the ball until they’re harassed at which point they release a switch to the open space on the opposite flank where the ball lands either behind the winger or ahead of the backline player, allowing a reset or immediate overload of the new side.

Important note: Due to Stanišić being right-footed, until Davies is fit to play again, Kimmich should never move to the left side of the back-three. The transition is just really awkward. He either plays on the right or in the middle.

Here we see the beginning of the next variation to be used against two-striker presses, which has Kimmich in the middle of the build-up unit. Notable immediate changes include the distance between the pivots increasing massively, as well as Jackson joining the midfield to form a diamond of sorts. What happens with the ball all depends on how the opposition adapt to this shape. This one gets quite intricate, so we’ll take it bit-by-bit.

Our first variation showcases the responses to two things: a non-committal central response from the opposition, and the wingers coming narrow to mark the pivot players.

The simple truth is that Kimmich will not release the ball unless he is pressed, instead inching forward until somebody breaks structure to challenge him. When he does, the wingers and Jackson immediately spring into action, with the wingers dropping a few steps to gain time away from their marker so they can play a first-time ball into the centre where Jackson is running in (marked in yellow).

The other adaptation is the team’s response to the opposition wingers coming narrow to mark the full-backs who have formed the pivot. This results in the centre-backs (yes, the CENTRE-BACKS) pushing down the line behind the back of the opposition winger (marked in purple), receiving either, if they get the space, directly from Kimmich, or more likely, as a backpass from a receiving winger. I’ve put these two ideas together here to showcase just how potent they are when utilised together, with Olise having the option to play Kane, Jackson, or Upamecano in this position once he receives from Kimmich. The following variations will include the opposition wingers narrowing as it’s really the only logical response to this pivot, anything else leaves major gaps in structure that can be exploited with ease (either you are letting the pivot players receive for free, or are pushing a player ahead to mark them which will leave one of the five attackers free).

If the midfielders commit to the press, it only gets more dangerous as now the lane to the wingers is far more open for Kimmich to thread the needle through, and now Olise can receive on the turn instead of being forced into a backpass or holding the ball up. Jackson can once again make a run in, anticipating a through ball from Olise.

If one of the strikers commit a press to Kimmich, it obviously opens up the centre-back behind them, either for a direct pass from Kimmich or a wall-pass utilising Neuer. With the opposition wingers tying down the inverted full-backs, this clears a passing lane from the centre-back to the winger, who drops a few steps to gain time on the ball when they receive. These few steps will also create a bit more space for the full-back to run into if the winger elects to play a pass into the half-space.

There is simply no way to stop Bayern from progressing the ball, and it’s mostly thanks to the ridiculous profiles this squad has accumulated over the last few years, capable of doing these sorts of things with ease. But we’ve known this, and Kompany has had absolutely no trouble keeping the ball and getting it forward since joining. It’s in the box that has been the real issue — well, it’s more the finishing which isn’t something that tactics can fix — with chance creation being spotty at times against certain opposition. Let’s tackle the final third.

Weaving mating nets: Breaking down the castle walls

Us and them, and after all, we’re only ordinary men.

Now I thought about what I wanna say, but I never really know where to go

So I chained myself to a friend, ‘cause I know it unlocks like a door

There’s of course several lanes for Bayern to attack from, but I think that the centre has far too many variables to create structured situations for the team to exploit, it’s all in transition. What we fill focus on, however, is where the team starts the majority of its infiltrations from, and out wide.

The reason most if not all top teams prioritise chance creation that starts from wide is because the wide areas of the pitch have far less variables to account for, thus resulting in far more controllable situations, as well as of course the natural consequences of having the ball on one extreme of the pitch: it opens up spaces on the other end. Let’s look at how our wide attacks work.

Note: While all the attacks here are shown on the left side, the right side will have the same patterns, just mirrored. The strikers shift over, so on the opposite side, Kane would be the close short option and Goretzka would become the far-side player tying down the centre-back (Jackson’s role remains the same, near-side centre-back area).

We start by looking at what the situation looks like at a baseline when the ball is received by one of our wingers and they’re about to take on their man. This is the result of our previous build-up pattern utilising Stanišić as a magnet for the press and bypassing them utilising Kim’s wide positioning opening a passing lane down the line. The primary problem to address is the numerical advantage that the opposition currently holds, caused by their lack of high-pressers. This can immediately be solved, however.

The first pattern doesn’t address these issues directly, rather it just relies on simple footballing principle: If you get there ahead of your man, you get the ball. Here, Goretzka gets close to the ball, getting distance between him and his man which lets him play the ball through to a running Jackson or carry the ball forward himself.

At the same time, Stanišić pushes into the space marked, meaning that if Goretzka’s marker stays tight to him, the passing lane to Stanišić opens up, and Kane is already dropping into the space between the lines to receive a pass from Stanišić. It’s also important to note Kim pushing forward a few yards once again, making him an option for the backpass as well as committing the opposition winger to coming yet deeper to watch him. Kim’s recovery pace means that there is very little chance the winger can outpace Kim in the event of a counter-attack, and actually, putting both of them further away from goal only increases the time Kim has to catch up, which, rather counterintuitively, means that pushing up is safer than staying deep.

The second pattern is what makes Nicolas Jackson such a valuable asset to this team. There’s a reason I’ve curated the structure to put him in the same role no matter what side the ball is coming from.

Yes, he can play up-front and do all of the ball-striking things, but perhaps his most underrated ability is how he can hold the ball up and escape pressure from multiple players at once. Here, with Goretzka not attacking that space (yet), Díaz plays a pass through to Jackson, and in the diagram Jackson plays the safe pass to the incoming Laimer who can then play Kane in, or, if he’s blocked off, play a lofted ball to Kimmich out wide. However, looking at it on grass and not on whiteboards, Jackson very much has the ability to hold up the ball and play Kane in himself or just turn his man and take the shot himself. That’s just the kind of player he is, and it’s what makes him such a unique profile. I’m serious, guys, watch out for Jackson, he’s been a player I’ve loved watching for a while (although he does suffer from a terminal case of Bayern DNA, i.e. he’s a big-chance-missing machine).

There’s also a very sneaky idea here once the ball comes to Kimmich, and it’s the far post run from Goretzka that creates a 3v2 aerial duel using both the strikers and Goretzka against the centre-backs if the player on Goretzka doesn’t react quickly enough to the run.

Speaking of far post overloads, that’s our final chance creation pattern for today.

It begins with Goretzka drifting wide instead of attacking the channel, which may seem counterintuitive as there’s already a passing option there in Kim. However, this allows Kim to drop deep — which will be relevant later — and more importantly, opens up a lane in the half-space for Stanišić to crash. More importantly, Laimer moves all the way up into the opposition’s defensive line, dragging a player with him, which leaves the centre open.

Upamecano can come barging through this space as a libero, aided by the fact that Kim has dropped off and can cover the space left behind him. The opposition now have a choice, let Upamecano have a free run at the edge of your box, or commit a man to him. If you commit a man to him, suddenly there’s a 4v3 at your far post.

Oops. Eins null.

“Out of the way, it’s a busy day, I’ve got things on my mind!”

For want of the price of tea and a slice, the old man died.

That does it for this whiteboard piece iterating upon Bayern’s strong tactical fundamentals, adding little details here and there (most notably in how the defensive pieces move) to add more threat in certain areas. What did you make of it? Is there anything I’ve missed that you would’ve added? Let us know in the comments, and stay tuned because a sequel is planned for this week, going over potential transfer targets for next summer with this system in mind.

Bayern Munich’s transfer window has been wild and the team has some, well, gaps. How can things all come together?

Let’s explore what has been happening, where things might be going, and why not everything has looked great so far on this edition of the Bavarian Podcast Works Show:

- Fans are frustrated, but it is not time to panic. There are reasons for the issues we are seeing.

- How does Bayern Munich end up in these transfer situations? Nicolas Jackson-to-Bayern Munich became a complete mess.

- Bayern tried to get Atalanta’s Ademola Lookman.

- There seems to be heat in the Bayern offices and it seems to be wearing on Max Eberl.

- Have we already seen the best of Aleksandar Pavlović?

- Erik ten Hag on the hot seat?