Casey Stengel called him the “strangest man ever to play baseball,” which, coming from “The Old Perfessor”, is notable. His career somehow spanned 15 seasons, even though he was just a career .243 hitter and only accrued six home runs in 1,962 plate appearances. He spoke seven languages and would often confer with his Princeton teammates in Latin. He had no connection to Kansas City but remains one of the more colorful and interesting stories in baseball history.

His name was Morris “Moe” Berg. He

was born May 3, 1902, to Jewish immigrant parents and lived much of his life in and around New York City. A precocious child, he begged his mother to let him start school at the age of 3½. He began playing baseball at the age of 7 for his local church team under the pseudonym “Runt Wolfe.” He graduated magna cum laude from Princeton, where he played shortstop and was captain of the baseball team. In June of 1923, the Tigers lost to Yale at Yankee Stadium, but Berg had an excellent day, making several fine plays in the field and collecting two hits. The New York Giants and the Brooklyn Robins both wanted to have a Jewish player on their roster and expressed interest in signing Berg. On June 27, he signed with the Robins for $5,000.

As it often was in old-time baseball, Berg made his Brooklyn debut the same day against the Phillies at the Baker Bowl. He entered the game as a defensive replacement in the seventh inning, handled five chances without error, and collected his first major league hit—an eighth-inning single off Clarence Mitchell. Berg appeared in 49 games but hit just .198.

After the season, Berg took his first trip overseas, living in Paris and traveling through Italy and Switzerland. After spring training, the Robins optioned Berg to their Minneapolis affiliate due to his poor hitting. He spent the next two-plus seasons bouncing around the minor leagues—Minneapolis to Toledo to Reading—before the Chicago White Sox picked him up for the 1926 season. Over the next two seasons, Berg was habitually late reporting for spring training as he completed classes at Columbia Law School. He would report in late May, then typically spend most of the summer on the bench until injuries to other players gave him a chance to play. During this time, the White Sox moved Berg to catcher.

He grew into an outstanding defensive catcher, often appearing near the top of the league in caught stealing, assists, and double plays. His bat came around a bit as well. He hit a career-high .287 in 1929 while appearing in 107 games with 47 RBI, also career highs. He received some down-ballot MVP votes for the only time in his career.

In April of 1930, Berg tore knee ligaments in an exhibition game, and the injury hampered him for the remainder of his career. The White Sox released him after the 1930 season. The Cleveland Indians picked him up, but he appeared in only ten games while battling his balky knee. After being released by Cleveland, he signed with the Washington Senators, appearing in 75 games in 1932.

It was during this time that Senators outfielder Dave Harris came up with one of the all-time great baseball quotes. When told that Berg could speak seven languages, Harris replied, “Yeah, I know—and he can’t hit in any of them.” Another former teammate said, “Moe was really something in the bullpen. We’d all sit around and listen to him discuss the Greeks, the Romans, the Japanese—anything. Hell, we didn’t know what he was talking about, but it sure sounded good.”

Always a world traveler, Berg sojourned to Japan after the 1932 season along with Lefty O’Doul and Ted Lyons. Their purpose was to teach baseball seminars at Japanese universities. After the assignment ended, Berg stayed in Japan and later toured several other Asian and European countries.

Berg reached his only World Series in 1933, but the Senators lost to the Giants in five games. Berg did not see action in the Series.

After the 1934 season, Berg made a second trip to Japan to play against a team of Japanese All-Stars. On the American team, Berg was an outlier: a no-hit, third-string catcher making the trip with the likes of Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Earl Averill, Charlie Gehringer, and Jimmie Foxx. While in Japan, Berg—under the guise of visiting the daughter of the American ambassador—went to the top of St. Luke’s Hospital, one of the tallest buildings in Tokyo. Using a 16mm Bell & Howell movie camera, Berg filmed the city and the port.

This was the juncture where Berg’s career began to turn. He continued to play in the majors, spending the final five years of his career with the Red Sox before retiring after the 1939 season at the age of 37.

He collected two hits in his second-to-last game, playing on a Red Sox team loaded with stars such as Jimmie Foxx, Ted Williams, Bobby Doerr, and Joe Cronin. Berg’s last major league hit was a home run off Tigers pitcher Bud Thomas at Briggs Stadium.

Berg then went into coaching for Boston for the 1940 and 1941 seasons. In 1941, Berg penned a piece for The Atlantic Monthly entitled “Pitchers and Catchers.” I’ve read part of it, and it struck me as a piece as relevant today as it was in 1941. The Royals, and other teams, would benefit from having all catchers in their systems read the story.

After Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, Berg went to work for the Office of Inter-American Affairs, where he screened his Tokyo movie footage for U.S. intelligence officers. In February 1942, he made a radio plea to the Japanese people in their own language, warning them that they had been betrayed by their leaders and could not win the war.

In 1943, Berg went to work for the Office of Strategic Services, the predecessor to today’s CIA. His fluency in several languages and his charismatic personality made him a perfect spy. Thus, Moe Berg became the James Bond of baseball.

Berg eventually worked on something called Project Larson, whose goal was to kidnap Italian rocket and missile specialists and bring them to the United States. In 1944, Berg was working in Europe. His major assignment was to attend a lecture in Zurich by German physicist Werner Heisenberg to determine how close Germany was to developing the atomic bomb. Berg’s orders from Franklin Roosevelt were that if he believed Germany was close, he was to assassinate Heisenberg, in the lecture hall if necessary. Berg carried a pistol and a cyanide capsule to the event.

Berg later dined with Heisenberg and concluded that Germany was not close to developing the bomb. Heisenberg lived.

Berg later convinced Antonio Ferri, head of Italy’s supersonic research program, to relocate to the United States and take part in the development of supersonic aircraft. To this, FDR quipped, “I see that Moe Berg is still catching very well.”

Ferri would go on to play a major role in the development of supersonic and hypersonic jet engines for the United States.

After the war ended, Berg seemed to lose interest in life. He did some work in the early 1950s assessing the Soviet Union’s atomic bomb development, but the project never gained traction. President Truman awarded Berg the Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor given in wartime. Berg refused the honor without explanation.

He endured long stretches of unemployment, first living with his brother and later—after being evicted by his brother—with his sister. He died on May 29, 1972, in Belleville, New Jersey, at the age of 70. His final words were reportedly, “How did the Mets do today?”

After Berg’s death, his sister Ethel requested and accepted Berg’s Medal of Freedom, which she donated to the Baseball Hall of Fame. She took Berg’s ashes to Israel, where they are buried in an unknown location.

Berg’s exploits were the subject of at least three books and one feature film titled The Catcher Was a Spy. Berg was portrayed by Kansas City’s own Paul Rudd. Due to financial distress, Berg made a late-life attempt to write an autobiography. That project collapsed when the prospective author mistook Berg for Moe of the Three Stooges. Berg, highly and rightly offended by the faux pas, pulled the plug on the project, and his secrets died with him.

Berg was an unusual character. His father once criticized him for wasting his intellectual talents on baseball, to which Berg replied, “I’d rather be a ballplayer than a justice of the United States Supreme Court.” Such is the love affair many men have with baseball.

Of course, WAR didn’t exist in Berg’s time, but his numbers need little explanation: 663 games over 15 years, 1,813 at-bats with 441 hits, six career home runs, and 206 RBI. He also stole 12 bases. His career slash line was .243/.278/.299. His career WAR, calculated years after his death, was a negative 4.7.

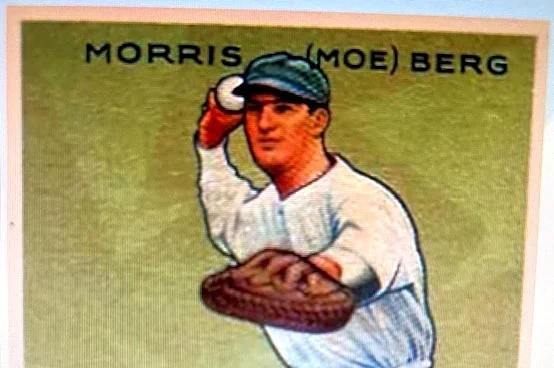

Despite those pedestrian numbers, Berg received four votes for the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1958 and five more in 1960. He was inducted into the National Jewish Sports Hall of Fame in 1996, and his baseball card is the only one on display at CIA headquarters. His 1933 Goudey card remains a classic, showing Berg crouched behind the plate without equipment, holding the ball in his right hand, preparing to throw it back to the pitcher.

I doubt we’ll ever see another Moe Berg. Prior to his death, Berg said, “Maybe I’m not in the Cooperstown Baseball Hall of Fame like so many of my baseball buddies, but I’m happy I had the chance to play pro ball and am especially proud of my contributions to my country. Perhaps I couldn’t hit like Babe Ruth, but I spoke more languages than he did.”

As a recent beer commercial opines, Moe Berg may very well have been the most interesting man in the world.