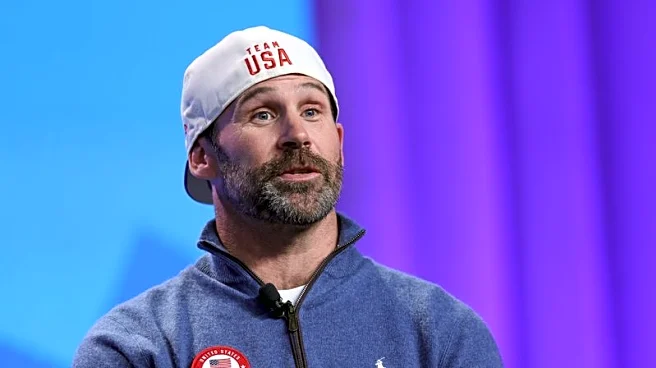

Good news: you’ve been invited to appear on the Monty Hall show. And so, being a savvy contestant, you brush up on the rules of the game (and the infamous logic puzzle it gave rise to). You give yourself your pep talk. You tell your excited friends and family to watch. You’re ready. But when you arrive on the day of the taping, you discover, to your great shock, that you’ve actually been invited to appear on the Monty Phil show. And the host—an oddly familiar, suspiciously green fellow who doesn’t

say much— invites you to play their best game: Nola or Mystery Pitcher?

The way it works is simple. Behind Door #1 is Aaron Nola. Behind Door #2 is a pitcher whose name and face you do not know. All you know about him is this: statistically, he is the pitcher most similar to Zack Wheeler. So you think. And you ponder. And eventually, you tell the host you’ve made your decision. You want the mystery pitcher, the closest you can get to Wheeler without actually getting Wheeler. And so Door # 2 rises to reveal… Aaron Nola?

Yes, it’s true. Statistically, there is no pitcher, across Major League Baseball’s entire history, who resembles Zack Wheeler more than Aaron Nola. But “statistically” is something of a weasel word: there’s lots of statistics, and some of them are more meaningful than others. So it’s best to be precise. Here we’re talking about Similarity Score, a measure developed—like so much else of our modern tools for thinking about baseball— by Bill James. The idea is simple: you start with 1,000 points, then subtract points for differences between the two players in major categories. The higher the score, the more similar the players are. Baseball Reference helpfully provides the breakdown (as well as Similarity Scores for every player, both in general and at given ages; highly recommended if you have some time to kill). For pitchers, the subtractions are as followed (taken directly from the B/R website):

- One point for each difference of 1 win.

- One point for each difference of 2 losses.

- One point for each difference of .002 in winning percentage (max 100 points).

- One point for each difference of .02 in ERA (max 100 points).

- One point for each difference of 10 games pitched.

- One point for each difference of 20 starts.

- One point for each difference of 20 complete games.

- One point for each difference of 50 innings pitched.

- One point for each difference of 50 hits allowed.

- One point for each difference of 30 strikeouts.

- One point for each difference of 10 walks.

- One point for each difference of 5 shutouts.

- One point for each difference of 3 saves.

Subtract ten points if there’s a handedness difference. The points subtracted for difference in winning percentage can be no greater than 1.5 times the sum of the points subtracted for wins and losses, so make that adjustment if needed.

Aaron Nola and Zack Wheeler have a 957.8 Similarity Score. That is the highest for either of them, meaning that Nola has no stronger comparison than Wheeler, and Wheeler has no stronger comparison than Nola. That might come as a surprise, given the disparate ways the two are discussed: Wheeler as the true ace, questioned by few, Nola as the polarizing figure, seen by some as a valued contributor and others as a source of frustration. To get to the bottom of this, we can take a closer look. Let’s go beat by beat and see where Nola and Wheeler lose similarity points, and where they don’t.

One point for each difference of 1 win: Wheeler has 113 wins to Nola’s 106. Seven points subtracted.

One point for each difference of 2 losses: Wheeler has 75 to Nola’s 86. 5.5 points subtracted.

One point for each difference of .002 in winning percentage (max 100 points): Wheeler’s win percentage is .601 vs. Nola’s .552. 24.5 points. But since this can be no more than 1.5 x the sum of the above two lines, this becomes 18.75 points subtracted.

One point for each difference of .02 in ERA (max 100 points): Wheeler’s career ERA is 3.28 vs. Nola’s 3.8. 26 points subtracted.

One point for each difference of 10 games pitched: Wheeler has pitched in 283 games vs. Nola’s 279. No points subtracted.

One point for each difference of 20 starts: All of Wheeler and Nola’s appearances have been starts, so this is identical to the above. No points subtracted.

One point for each difference of 20 complete games: Wheeler has thrown 5 complete games to Nola’s 6. No points subtracted.

One point for each difference of 50 innings pitched: Wheeler has pitched 1728.1 innings to Nola’s 1679.1. That’s a difference of 49 innings, so no points subtracted.

One point for each difference of 50 hits allowed: Wheeler has allowed 1475 hits to Nola’s 1494. A difference of 19 hits; no points subtracted.

One point for each difference of 30 strikeouts: Wheeler has K’d 1820 hapless batters, Nola 1841. A difference of 21 strikeouts; no points subtracted.

One point for each difference of 10 walks: Wheeler has walked 490, Nola 439. 5.1 points subtracted.

One point for each difference of 5 shutouts: Wheeler 3, Nola 4. No points subtracted.

One point for each difference of 3 saves: Not a single save for either one of them. Slackers. No points subtracted.

(Note: if you add up those numbers, they don’t quite match the 957.8 score Baseball Reference provides. I assume the error is mine and not BR’s, but for the life of me I can’t figure out where the mistake is. Leave a comment if you spot it).

Long story short: Nola and Wheeler are remarkably similar in so many categories. They’ve pitched for 11 years each, accruing similar numbers of appearances, hits, Ks, and innings pitched. The main difference between them is in ERA and winning percentage. Granted, though, both matter a great deal. When we think about how good a pitcher is, how reliable they are, we are likely to think first about their ERA (or perhaps their FIP; but Wheeler outdoes Nola there too, 3.29 to 3.5). And while the pitcher win is no longer in the good graces of the sabermetrically inclined (and for good reason), how likely a team is to win when a given hurler is on the mound is, of course, somewhat relevant.

And there’s other statistics that aren’t incorporated into Similarity Score that are rather pertinent to how we think about Nola, both in a vacuum and in comparison to Wheeler. Ask a Phillies fan about him, and they’re likely to bring up the homers. Nola allows 1.1 homers per 9 innings, and Wheeler allows 0.86. There’s also consistency: as Michael Baumann demonstrated at FanGraphs, Nola really is one of the more inconsistent pitchers in the league, capable on any given day of giving you an ace-caliber start or a total meltdown. Wheeler, like all hurlers, has bad days, but he’s much less up and down than Nola is.

Timing plays a role in our assessment, too. Wheeler has only been a little more valuable than Nola across the whole of his career by fWAR: 41.2 to 37.2. But Wheeler has posted 26.7 fWAR in his past five seasons (counting this one), and Nola has posted 17.7 in the same time frame. Wheeler’s been at his best during the Phillies’ current contention window, with all three of his top seasons by fWAR coming since the start of 2022, whereas only one of Nola’s has.

All of which is to say: Nola both is extremely similar to Wheeler, but different in a few crucial ways. You could make an argument that Wheeler’s truest comparison would be someone else, another one of the league’s truly consistent aces. And it would be a very fair argument. But the argument for Nola as the top match, while not perfect, holds some water. Nola has brought a tremendous amount of production to the Phillies. Per similarity score, his closest peers after Wheeler are Kyle Hendricks and Yu Darvish; not true aces, perhaps, but excellent hurlers all the same. If we argue, and I would say correctly, that Nola is not quite the pitcher Wheeler is, we also ought not to forget that he’s still a very fine pitcher. Nola is not Wheeler’s identical twin. But they’re at least fraternal.