As we get deeper into the postseason, closer to the offseason, and further away from the nightmarish end to the Mets 2025 campaign, a common question pops up for this team and this organization: what in the world

happened here?

If you have not been paying attention, or did a Men In Black-style mind wipe, Jeff Passan put it in a tweet that is succinct enough, and blunt enough, to jog your memory:

It is really hard to fathom that happening in a season. They were the best team in the league, record wise, for months. While it did feel like there was s0me regression coming, mostly because they never really hit or pitched well enough at the same time during that 45-24 stretch, it never felt like a collapse of this magnitude was possible — it just felt like they banked enough wins on the front end of the season that they would sneak by a surprisingly weak National League playoff race. And, even with all of that being said, they somehow still controlled their own destiny going into the final weekend of the season.

All they needed to do was get it done against the Marlins. They did not. Welcome, by the way, to a new generation of Mets fans who have their own “not getting it done against the Marlins”.

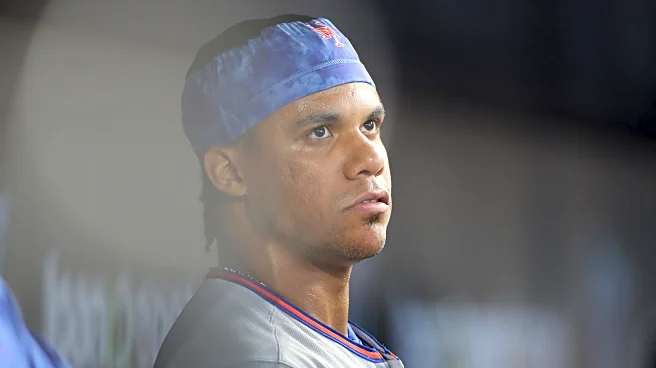

If you could boil down the Mets season into one image it would be this:

But the burning question is, why?

Well, personally, I boiled it down to two different things: a under the radar massive amount of injuries, and really inconsistent offense.

It did not really feel this way, or get talked about a lot, but the Mets were a very injured ball club, especially on the pitching side of things. Starters Sean Manaea, Griffin Canning, Frankie Montas and Tylor Megill all missed significant time with injury. In Manaea’s case, it was clear that it hampered him when he returned as well, considering he had a 5.64 ERA in 60.2 innings pitched, and generally became batting practice after the fourth inning or so, suggesting that the loose bodies in his elbow were, in fact, a problem for him. In Canning, Montas, and Megill’s case, they had season ending injuries that also will effect their 2026 seasons — and for Montas, he was probably never healthy to begin with. Kodai Senga was one of the best pitchers on the staff before an errant Pete Alonso throw derailed his hamstring, which in turn derailed his season: a season that ended with a trip to Triple-A Syracuse in September.

The injury bug hit the relievers too. A.J. Minter, Max Kranick, Dedniel Núñez, and Danny Young all suffered season ending injuries, and Reed Garrett will miss all of next season due to Tommy John surgery.

The sheer amount of pitching injuries is nearly impossible to overcome, and for the Mets it proved to be just that. While Nolan McLean came up and was excellent — one could argue ace-worthy — the other two top pitching prospects in Jonah Tong and Brandon Sproat looked more like prospects than they did pitchers who are ready to carry a rotation into a playoff run. On top of that, the bullpen was constantly cycling arms, as evidenced by the fact that the Mets literally set the MLB record for the most pitchers used in a season. While that is an effective way to keep guys fresh over a 162 game campaign, it reached levels of unsustainability rather quickly, with the frequency of future Immaculate Grid legends occupying the bullpen reaching levels never before seen. It is just nearly impossible to win that way.

While the pitching side bore the brunt of the injuries, the offense had its fair share too. Francisco Alvarez was hurt quite a bit, and played through multiple hand injuries. Jesse Winker, who was supposed to be a regular part of the DH rotation, played a grand total of 26 games, and Jose Siri, who was supposed to split center field with Tyrone Taylor (and frankly, probably helped cause Taylor’s rough season because he was overexposed in the everyday lineup), played in just 16 games before he was DFA’d. Luis Torrens and the aforementioned Taylor also missed time. Brett Baty missed the final games of the season, as well.

When you write it all out like this, the raw amount of injuries feels large and genuinely impactful, and truly hard to replace during the season. While every baseball team has contingency plans (and, likely, contingency plans to the contingency plans), there are only so many signings you can make to protect yourself against injuries of this volume.

Injuries are a big part of how things went sideways in Queens this year, but it was not the only thing. The second big issue they had was a weird and inconsistent offense.

The Mets finished tied with the Blue Jays for fourth in wRC+, coming in at 112 (just one point behind the dual second place finishers in the Dodgers and Mariners, all of which are playing in the Championship Series). However, they were all the way down in 10th in total runs scored. While that is not the most significant difference in the world, it is something that shows itself when the Mets missed the playoffs by a single game.

The Mets suffered from poor sequencing all year, from the difference between their wRC+ and their raw runs scored, down to never having a comeback after the eighth inning when trailing. And, personally, my theory is that their lineup was extremely top heavy.

FanGraphs.com" />

FanGraphs.com" />

The table above is the Mets sorted by wRC+, with at least 50 plate appearances — so basically anyone who played a semi-significant amount of time.

Juan Soto, Pete Alonso, and Francisco Lindor were themselves — they missed two games between the three of them and they all hit well. Francisco Alvarez was their fourth best hitter, but injuries took a lot of time from him, and he was replaced by two well-below average hitters in Luis Torrens and Hayden Senger, which was a huge net-negative while Alvarez was out.

Starling Marte was another solid contributor, but he played less than 100 games due to his inability to play the field and him splitting DH duties. However, they never found a suitable partner for him since Jesse Winker’s back injury forced him into a lost season.

Brett Baty ended the year well, but the context of his season is interesting. He started so poorly he was demoted for a time, came back up, had a 92 wRC+ in the first half, and a whopping 135 wRC+ in the second half.

Brandon Nimmo and Jeff McNeil were solid but unspectacular.

It felt as though, for large swaths of the season, if the trio of Lindor/Soto/Alonso did not get it done, no one would, and that is simply not a way to live; especially when the pitchers are all hurt.

The 2025 Mets felt like a perfect storm of things going extremely wrong. The pitchers were constantly hurt, the batters, outside of the big three, were average to inconsistent to downright disappointing, depending on which batter you are talking about. Those two reasons are certainly not the only ones, too. David Stearns himself also shouted out the defense as a huge issue that he needs to correct, for example.

In order to collapse to the level the Mets did, multiple things need to go wrong. A thing I often say involving a baseball loss is that it is usually everyone’s fault; despite the battles on a baseball diamond being more individual than a football field, a soccer pitch, or a basketball court, you lose a game, or in the Mets case, a season, as a group. As a whole, the injuries, poor offensive sequencing, inconsistent hitting behind the big three, the poor defense, and everything else culminated in one of the worst perfect storms you can imagine.

The fortunate thing, despite it being hard to believe as we sit here in mid-October, is that these things largely balance out over time. It will be hard to believe, but the sequencing will be better, the pitching healthier, and this could be a distant memory soon — David Stearn’s Brewers, for example, blew a (much smaller, mind you) three game lead in 2022, missed the playoffs entirely, and then rattled off three NL Central titles in a row, and are set to play for the National League Pennant after having the best record in baseball. 2022 is now a distant memory for that organization.

2025 was bad, no doubt, but it took a frustrating series of events to get there.