The hot stove is starting to heat up this month as players find homes before spring training. The Yankees brought back Cody Bellinger. The Mets landed Bo Bichette and traded for Freddy Peralta and Luis

Robert Jr. And the Dodgers made the biggest move, landing top free agent Kyle Tucker with the largest average annual value contract in baseball.

What you’ll notice about all those moves is that they were all made by the highest-revenue clubs in baseball. The Yankees, Mets, and Dodgers enjoy enormous protected territorial markets that they exploit for massive revenues. Seven of the top nine highest-paid players in 2026 play for one of those three teams. Baseball has a very soft “cap” in a luxury tax threshold with penalties starting at $244 million, but teams have zoomed past that with little worry.

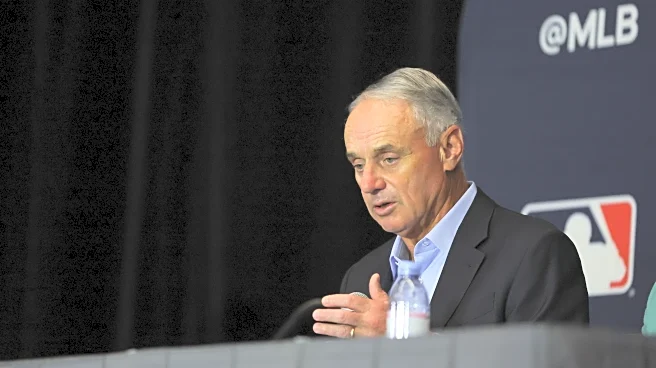

The escalating free agent costs and growing disparities of clubs has “enraged” MLB owners, according to a report by Evan Dreilich at The Athletic this week. With the Collective Bargaining Agreement expiring at the end of the season, he writes that owners are more determined than ever to get a salary cap in the game.

Major League Baseball owners are “raging” in the wake of Kyle Tucker’s free agency agreement with the Los Angeles Dodgers and it is now “a 100 percent certainty” that the owners will push for a salary cap, one person briefed on ownership conversations who was not authorized to speak publicly told The Athletic.

“These guys are going to go for a cap no matter what it takes,” the source said.

The NFL, NBA, and MLS all currently have salary caps, but MLB players have successfully resisted one for decades. Owners planned to unilaterally implement one after the 1994 season, which helped lead to players going on strike that August, leading to the cancellation of the World Series. The union has historically treated a salary cap as a non-starter, arguing that it caps top salaries, and unlike players in other sports, baseball players must work for years – sometimes up to a decade – at well-below market salaries. Last year, current MLB union head Tony Clark has reiterated the players’ stance against a cap.

“A cap is not about any partnership,” Clark said. “A cap is not about growing the game. That’s not what a cap is about. As has been offered publicly, a cap is about franchise values and profits. That’s what a cap is about.

Drellich reports that owners will meet next month to shape a proposal for players later this year, with 22 of the 30 owners needed to approve any plan. He reports that some small market clubs have reservations about a salary floor that would cause them to spend more on players. But Dreilich argues that the market valuation of each franchise would instantly rise if a cap is implemented.

The CBA expires on December 1, and everyone seems to be anticipating a work stoppage of some sort next offseason. Baseball’s last work stoppage was in 2022, although it was resolved in spring training, and the regular season was pushed back a week with no cancellation of games. The 1994-95 work stoppage was resolved in late March of 1995 when the National Labor Relations Board ruled for the players, and US District Court Judge Sonia Sotomayor issued an injunction to return to the old agreement. Players have generally shown an appetite to wait out owners, but the uncertainty for many clubs regarding their TV deals may give them more incentive to hold out as well.

The losers in this will likely be the fans. Fans of smaller-market teams watch helplessly as big-market clubs scoop up all the stars, and small-market owners sit on their hands. Fans are asked to pony up for season tickets and an ever-growing bill of streaming options to find their team, while games may not even happen in 2027. Baseball took a major hit in popularity with the extended work stoppage in the 90s. With more entertainment options on the table for consumers now, baseball may not be able to survive another prolonged labor fight that asks fans for patience while giving them little reason to stay invested.