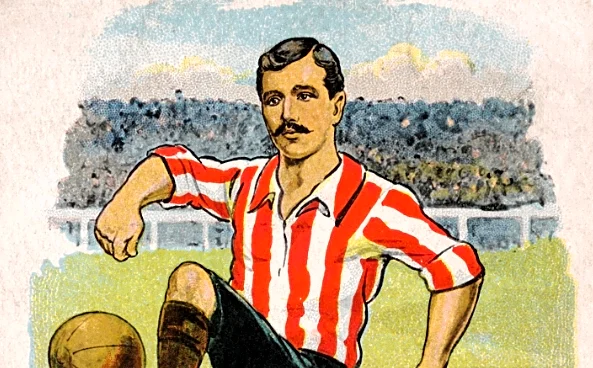

It was Sunderland’s first full season at their new home of Roker Park when Andrew McCombie arrived from Inverness Thistle in December 1898.

He was an imposing figure at right-back, but looks were deceptive as was his physique. This was a ball-playing defender who combined traditional defensive attributes with a subtle and intelligent ability to play the beautiful game.

He made his debut on 18 February 1899 in a one-nil victory against Sheffield Wednesday in South Yorkshire, coming in for Phil Bach,

and but for the odd niggle he remained a permanent feature at full-back till he left the club in February 1904.

He played every game of the following season (37) as Alex Mackie’s men saw their title charge just fall away to Aston Villa in the final stages of the 1899/00 campaign and they finished third.

In 1900/01 McCombie missed only one game all season as the Lads went one better than the previous season and finished in second place, two points behind champions Liverpool.

McCombie was, along with keeper Ned Doig, showing remarkable levels of consistency in defence, not only in appearances but levels of performance.

Building on their runners-up spot, Sunderland went one better in 1901/02 and won the title for a fourth time. With a remarkably stable defence of Doig, McCombie, Watson, Ferguson, McAllister and Jackson, and Gemmell, Millar and W. Hogg sharing 30 goals between them, Sunderland were deserved champions.

The 1902/03 season would see a close-run title contest fail by just a point as “The Wednesday” took the title and Sunderland finished in third position on goal average behind Aston Villa. Going into the last game of this season Sunderland were favourites to retain the title. A one-nil defeat at near neighbours Newcastle put the kybosh on that hope in dramatic and disappointing fashion. McCombie played all but two games of this campaign to at least retain his tremendous levels of fitness and appearances.

Season 1903/04 would prove to be a disappointing and traumatic one, as well as Andrew McCombie’s last for Sunderland.

Although they started the season in fine fettle ,winning five of their first six games, a season of changing personnel saw Sunderland’s challenge fade, and they finished in sixth position.

It also saw a dispute arise that would bring unwelcome national publicity to the club and see the hitherto excellent relationship between Andrew McCombie and the club end in dramatic fashion.

The dispute centred around a benefit match that had been agreed by the club for McCombie. Unusually the club had agreed that the league game with Middlesbrough could be used as the benefit match for the player. This was unusual (it was more common for friendly matches to be played midweek). Adding to the confusion, the club agreed a loan of £100 (around £14,000 today) to McCombie prior to the game, to allow him to purchase some pianos to start a business (McCombie was a piano tuner to trade), with the view from the club that he would pay this back from the proceeds of his “benefit” match. As was common practice when agreeing a benefit match, the club did promise to ensure that should the net proceeds to McCombie fall below £100 the club would make up the difference.

As if this was not enough to cause a furrowed brow, prior to the benefit match (league game against Middlesbrough, 9 January 1904), the board called McCombie into a board meeting to ask him not to sell tickets for the most expensive seats at Roker Park (2s 6d). He chose to ignore them and come the day of the game he had sold an estimated 15,000 tickets and as the club had agreed he could have the proceeds of any tickets he sold, he netted an estimated sum of over £500. The club on the day took approximately £60 on the gate, which did not cover even half of the club’s expenses for the week. The club had not had the best of seasons financially and had now lost out massively. They had not bargained on the interest and drawing power of Middlesbrough who were making their first visit ever to Sunderland for a game, as well as McCombie’s business prowess and popularity regarding ticket sales.

The sum netted by McCombie was a record amount and £250 higher than the previous best. The club at this juncture seem to have wanted to honour their commitment to McCombie to let him keep the ticket sale profit despite their loss on the gate and his refusal to stop selling the most expensive tickets.

What they did do was instruct club secretary Alex Watson on the Monday after the game (11 February 1904), to seek out McCombie and get the £100 loan returned to the club.

When he approached McCombie and asked for the loan to be returned, McCombie allegedly told him he would not get a £100 nor a 100 pence out of him!

The club asked McCombie to attend a hastily convened board meeting to discuss the matter and he was asked to return the loan, which he again refused to do. After another follow-up board meeting the club informed McCombie he would be placed on the transfer list if he did not repay the loan. He again refused, expressing his view that the £100 was a gift and additional to his benefit match earnings.

A gift such as this would contravene existing central committee (FA) rules at the time and it is not clear who contacted the FA, but they advised Sunderland to seek redress in the courts, to get to the truth of the matter.

In the meantime Andrew McCombie was placed on the transfer list and very quickly sold to neighbours Newcastle for £700, a record fee at that time.

Another moving part of this sorry tale is that part of McCombie’s keenness to make good on his benefit match and to get his business established was a concern (that he had not made public) about a leg injury he had and whether he was going to be able to continue playing for very much longer.

The case came to court in July 1904 and over the two-day hearing his honour Judge O’Connor heard crucial statements from a bank clerk (Mr Vidal) that Andrew McCombie had told him upon receipt of the £100 at the bank and in the presence of club secretary Mr Alex Watson, that the money was a loan and required to be repaid. Alex Watson (club secretary) confirmed this on the stand. Statements under oath from two directors James and John Henderson also provided testimony to the fact that the £100 was indeed a loan to be repaid from the proceeds of the benefit match. Match secretary (manager) Alex Mathie also provided testimony to discussions with McCombie about the loan and the understanding that this would require it to be repaid.

When McCombie came to give evidence, he said his understanding was the £100 was a gift towards his benefit and not a loan.

Given the consistent testimony of four men of standing and the lack of witnesses to the fact that it was a gift, the judge found for the club and ordered the loan and costs to be repaid. Now playing for Newcastle, the money and the loss of his good name in this instance must have been a blow.

This had all been played out in the local and national media and had whipped up a huge amount of interest and speculation.

In the background the Central Committee (FA) were more than keen observers of proceedings and upon completion of the court case, they commenced their own investigation. In the course of the case and evidence heard, a number of irregularities emerged. Tales of directors’ meetings being held on the hoof in the Bell’s Public House and the lack of accurate minutes and accountability had piqued central committee interest. An anomaly over the actual sum given to McCombie caused further concern. Not only had he been given £100 in the bank by Alex Watson, but a further £7 11s. This was described in court as expenses by Alex Watson and Alex Mathie for train fares to Inverness on a player scouting mission by Mathie and McCombie. However the actual amount of the return train fare to Inverness, when added to the £7 11s came to £10 and the view taken by the FA was this was an illegal payment paid to McCombie for re-signing for the club in the 1903/04 season (£10 was the permissible signing-on fee, but this was now a one-off payment only under recent changes to FA rules).

The judge had expressed some concern about some of the evidence given by the two directors and queried why John Henderson had resigned his post prior to the court case, especially after it emerged that he had claimed in front of Newcastle directors whilst negotiating the sale of McCombie that the loan was a personal one made by him to the player. This was proven not to be true, however raised further concerns about practices at board level. The judge had also acknowledged the defence solicitors’ concerns about the lack of any potent written evidence of the loan or the benefit match arrangements, again raising questions about the way the club was being run.

A lengthy and detailed investigation led to the suspension in November 1904 of Alex Mathie for four months plus all but one director was suspended from all football activities for two and a half years and the club were fined £250 for irregular practices.

It was a sorry chapter in Sunderland’s history and neither McCombie nor the club came out of it well.

The one director who was not suspended was Alderman Fred Taylor, an honourable and hard-working man. He set about rebuilding the board and the club, recognising that a crucial juncture had been reached and the club was in real danger. To his credit he succeeded in bringing some stability and credibility to the club over the next few years and laid the foundations for some success on the pitch too. Fred Taylor remained chairman till 1913 and on the Sunderland board till 1946.

Andrew McCombie played for Newcastle till 1910 when he retired to become Newcastle’s assistant trainer. He was promoted to head trainer in January 1928 and took the role of general assistant till his retirement in 1950, rendering over forty years’ service behind the scenes to Newcastle. Having won the league with Sunderland in 1902, he helped Newcastle to the title in 1905 and 1907 as well as losing FA Cup finals in 1905 and 1906.

Ironically his last goal for Sunderland was against Newcastle and he had the good grace to score an own goal in his first game for Newcastle against Sunderland.

His popularity at Sunderland was matched at Newcastle. He was a popular character with the players and his death at the age of 75 from a heart attack in his North Shields home was kept from the Newcastle players until they had finished playing their FA Cup semi-final on 28 March 1952. He had been at the ground the day before he passed away.