The Bronx. Manhattan. Brooklyn. Queens. Staten Island. New York’s five boroughs permeate the story of baseball, from its humble beginnings as a working class bat and ball sport in the mid-19th century,

to its explosion in popularity and commercialization in the late 1800s, through its emergence as the nation’s great pastime throughout the 20th century. And so, it was only fitting that, for the first World Series of the new millennium, the eyes of the baseball world would once more return to the city of its birth.

Living in the same city as the Yankees and playing in the same division as the dynastic Braves, the New York Mets spent much of the ‘90s lost in the shadows of their rivals after an early-decade implosion. Despite winning 88 games in 1997 and 1998 under new skipper Bobby Valentine, they did not earn a postseason bid in either season, finishing more than 13 games out of the division in both years and failing to secure the Wild Card bid. The ‘98 campaign was especially tough, as they led the Wild Card going into the final week, only for it to be winless. The Cubs and Giants duked it out in a Game 163 with the Mets at home. At long last, powered by Mike Piazza and the National League’s best offense, the Mets finally notched a postseason trip in 1999, beating the Reds behind Al Leiter in a one-game playoff for the Wild Card, walking off the upstart Diamondbacks in the NLDS, and reaching the NLCS before running into the Atlanta buzzsaw that ended their season (on a walk, no less).

Despite their success in the previous season, the Mets underwent a major retooling headed into 2000. First baseman John Olerud left in free agency, while left fielder Rickey Henderson fought with Valentine and forced his release in the middle of May. Todd Zeile was signed to replace the former, while a pair of youngsters in Benny Agbayani and Jay Payton were counted on to solidify the outfield. More significantly, though, the Mets decided they needed an ace-level pitcher to compete with the Braves’ three-headed monster, acquiring 1999 NL Cy Young runner-up Mike Hampton in a blockbuster deal with the Astros.

With Hampton set to hit free agency after the season, where he would receive what was then the largest pitching contract in baseball history from the Rockies, the move represented the Mets front office metaphorically pushing all their chips to the center of the table and going all in on the 2000 season. And, much like Kevin Brown’s single season in San Diego led them to just their second ever World Series appearance, the deal worked wonders for the Mets. Hampton was a veritable ace, striking out 157, posting a 3.14 ERA (142 ERA+), and accruing 4.6 fWAR in 217.2 innings. Somehow, he was just the team’s second-best starter, as the postseason veteran Leiter rebounded from a so-so 1999 campaign to fan 200 and accrue 4.8 fWAR in his age-34 season. While neither pitcher would be counted among Randy Johnson and Greg Maddux as the NL’s best, they gave the Mets a pair of top-flight lefty aces that few in the league could match. And should this pitching staff hand a lead to the bullpen, they came face to face with a fearsome trio of John Franco, Turk Wendell, and closer Armando Benítez.

Compared to their 1999 selves, the Mets lineup took a bit of a step back, finishing the season with a 99 wRC+ that, while fifth in the NL (remember, prior to the universal DH, NL teams generally put together lower wRC+ values than their AL counterparts due to the sheer number of uncompetitive pitcher at bats), relied heavily on Piazza (.324/.398/.614, 38 HR, 5.8 fWAR) and second baseman Edgardo Alfonzo (.324/.425/.542 .967, 6.4 fWAR). Behind them, the Mets had no bats that were truly fearsome, but they also lacked major holes — aside from shortstop, they got roughly league average play almost everywhere, and for a team with a strong pitching staff and a pair of elite hitters, basic competence across the diamond can go a long way.

The Mets easily won the Wild Card with 94 wins (the first time they reached the postseason in consecutive seasons in franchise history), and actually finished just one game shy of the Braves for the division thanks to a strong end to the season. And while the Cardinals would save them from a rematch with their division rivals, against whom they had gone 6-7 in the regular season, the Mets had a bit of a gauntlet to get through in the National League.

The NLDS saw the Amazins come face-to-face with a Giants squad that, thanks to icon Barry Bonds (.306/.440/.688, 49 HR, 7.6 fWAR) and MVP Jeff Kent (.334/.424/.596, 33 HR, 7.4 fWAR), boasted the Senior Circuit’s best offense. After losing the first game with Hampton on the mound, however, a pair of extra-innings wins—ones that saw Franco and Agbayani play hero—put the Mets in the drivers’ seat. Then, Bobby J. Jones, the team’s fourth starter who had a 5.21 ERA across the 1999 and 2000 seasons, spun a one-hit, complete-game shutout in which he struck out five to send to send New York to their second-straight NLCS.

The 95-win Cardinals swept the Braves in the NLDS, meaning that 2000 was the first season since 1990 that did not feature a League Championship Series in Atlanta. Despite this upset, however, the Cards limped to the finish. Years of abusing his body limited Mark McGwire to pinch-hitting as he delayed knee surgery. Catcher Mike Matheny severed two tendons and a nerve in his hand at the end of September while sheathing a knife he received for his birthday, ending his season. Starter Garrett Stephenson injured his elbow during Game 3 of the NLDS, an injury that ultimately required Tommy John surgery. Meanwhile, rookie starter Rick Ankiel — one of the team’s two healthy starting pitchers — lost the strike zone, the beginning of what would become a years-long battle with the yips. Up against a surging Mets squad, the battered Cardinals ultimately fell in five games, with the Mets securing the series win on the back of a complete-game shutout from Hampton, the NLCS MVP.

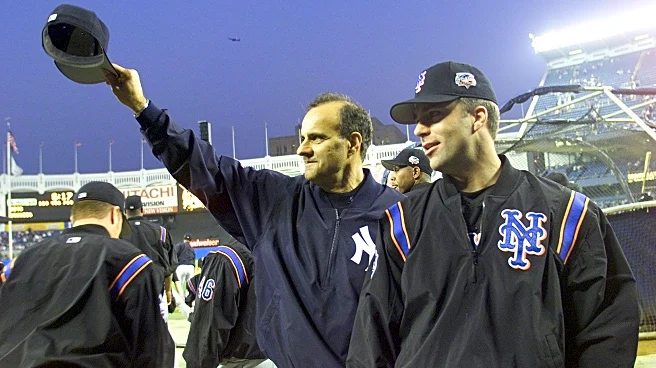

Twenty-four hours later and just a few miles to the west, David Justice played long ball and Mariano Rivera halted a furious Mariners comeback attempt in Game 6 of the ALCS. That pit New York’s teams against each other in the Fall Classic for the first time since the ‘50s, when the Dodgers and Giants abandoned NYC and headed out to California.

Game 1: Andy Pettitte vs. Al Leiter (10/21)

With four days between the end of the ALCS and the start of the World Series, both the Yankees and the Mets had the time and flexibility to rearrange their starting rotation, albeit within limits. Despite this chance, both squads decided to continue with the rotation as already lined up, at least to start the series. For the Yankees, that meant postseason veteran Andy Pettitte, coming off a dominant outing in Game 3 of the ALCS, would get the ball in Game 1 for the Yankees — a move designed in part to ensure that the controversy-ridden Roger Clemens would not pitch in Shea.

Opposing him was another veteran southpaw in Al Leiter. Thanks to the Mets’ quick victory over the Cards, Leiter was extremely well-rested, having last pitched in Game 2 of the NLCS when he allowed three runs on eight hits in seven innings, striking out nine in the process. A member of the 1992 and 1993 Blue Jays and the 1997 Marlins, Leiter had three World Series rings to his name, matching Pettitte — making this the rare postseason matchup between two pitchers seeking their fourth World Series title.

Game 2: Roger Clemens vs. Mike Hampton (10/22)

Ever since the Yankees announced their rotation for the World Series, baseball fans everywhere circled this one on their calendar. From a pure baseball perspective, this matchup was one for the ages, as the Yankees sent out their ace, a five-time Cy Young winner with an AL MVP under his belt, to face Hampton, the Mets’ big offseason acquisition. And yet, thanks to an incident on the eighth of July, when Clemens drilled Piazza in the head with a fastball, giving him a concussion, what should have been a highly anticipated pitching matchup was relegated to a sideshow.

In fact, it is in part due to this event — which unsurprisingly drew plenty of ire in Queens — that prompted Joe Torre to have his ace start Game 2, rather than Game 1. By starting the second game of the series, Clemens would not be able to return to the mound until Game 6, ensuring that he would not come to the plate and risk direct retaliation when the Yankees were on the road in Games 3, 4, and 5.

Of course, as baseball fans undoubtedly remember, this didn’t stop fireworks from breaking out…but that’s a story for another diary post.

Game 3: Orlando Hernández vs. Rick Reed (10/24)

With the series headed to Queens, the Yankees turned the ball over to Orlando Hernández. Despite his up-and-down regular season in which he battled injuries, El Duque had largely been reliable in the postseason, leading the Yankees to victory in Game 3 of the ALDS and Game 2 of the ALCS, plus making a cameo out of the bullpen in Game 5 of the ALDS. That being said, the myth of the unstoppable postseason Hernández had fractured a bit in the ALCS, as he surrendered six runs in seven-plus innings in Game 6 against the Mariners, earning the win thanks to the Yankees’ offensive outburst in the seventh.

Opposing him was Rick Reed. A veteran workhorse who gave the Mets 184 quality innings, Reed was making just his fourth postseason start despite being in his age-35 season. After a strong start to his postseason career — his first three October outings saw him go at least six innings and give up just two runs in each start — he crumbled in the NLCS, allowing five runs in 3.1 innings en route to the Mets’ only loss in the series.

Game 4: Denny Neagle vs. Bobby J. Jones (10/25)

Behind Pettitte, Clemens, and Hernández, the Yankees had no good options for the World Series rotation. In the end, they opted to go with Denny Neagle, the pitcher acquired in the summer to stabilize the rotation but who ultimately ended up as one of the rotation’s biggest sources of instability. After not taking the mound at all during the ALDS, Neagle made two starts against the Mariners — both of which the Yankees lost, in no small part due to Neagle’s inability to consistently throw strikes (in 10 innings across those two outings, he walked seven batters). Considering the other option was David Cone, a pitcher with a long postseason pedigree but who looked completely cooked, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that the team opted to go with the pitcher who had put together a quality outing more recently than August…although he did have a very short leash.

On the other side, the Mets sent out Bobby J. Jones (not to be confused with the other Bobby Jones who pitched for them that year). The veteran starter followed up his complete game shutout in the NLDS by surrendering six runs in four innings in Game 4 against the Cardinals, striking out just two and surrendering two homers.

Game 5: Andy Pettitte vs. Al Leiter (10/26)

With neither team needing to bring one of their intended starters out of the bullpen, both the Yankees and the Mets returned their Game 1 starters for what would ultimately prove to be the deciding Game 5. As it would turn out, fate gave each manager the arm they would have wanted for this situation anyway. Valentine certainly would have wanted to use his most experienced ace in Leiter when pushed to the brink. Pettitte, meanwhile, had become the Yankees’ series finisher, as he had been on the mound for Game 5 of the 1996 ALCS, Game 5 of the 1997 ALDS (they lost, but Pettitte pitched well), Game 4 of the 1998 World Series, and Game 5 of the 2000 ALDS.

So how would the series wind up playing out? As you can probably guess, although the Yankees had the worst record of all three teams the Mets faced in the postseason, their playoff experience allowed them to simply outlast their crosstown rivals, as they refused to break whenever they were figuratively punched in the mouth. As for the particulars, though, you’ll just have to wait and see.

Read the full 2000 Yankees Diary series here.