Postseason baseball has at atmosphere all its own. The Bleacher Creatures cause Yankee Stadium to shake. A wall of sound descends upon Fenway in its intimate quarters. When speaking to the media about their first trips to the postseason, players throughout the league regularly bring up the different vibe that exists on baseball’s greatest stage once the calendar turns from September to October, and their excitement to be a part of that action.

The very thought of postseason baseball invokes chaos

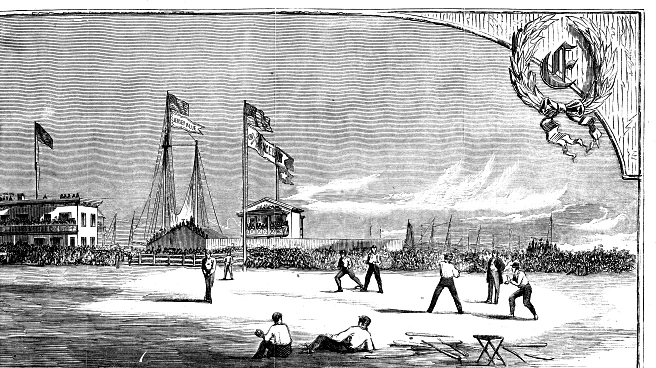

— but it wasn’t always that way. More than a century and a half ago, the Brooklyn Atlantics went down to Philadelphia to face the Athletics for the “East Coast Championship.” Despite its title, this wasn’t a formal championship in the modern sense; prior to the permanent organization of leagues and associations in the 19th century, the term “champion” bounced around in much the same way it does in athletic competitions like boxing — i.e., to become the champion, you must beat the preexisting champion. In this instance, the up-and-coming Philadelphia team invited the Brooklyn club to play a best-of-three series as part of a years-long project by Philadelphia investors to not only turn the team into a national force, but to prove that the sport of baseball, having exploded nationally through the American Civil War, was viable as a commercial enterprise.

Even as just an organized match between two teams, however, the Atlantics/Athletics series was highly anticipated by baseball fans throughout the country, not just within Brooklyn and Philadelphia, due to the success and prominence of the teams involved. According to The New York Times article from that day:

For a number of weeks past this match has been a prominent subject of conversation in sporting circles, both in this city and the leading cities of the Union. Since the inception, a number of years ago, of the exciting contests for supremacy at the national game of base ball, the Atlantic Club has occupied a very prominent position among the leading clubs of the country, and their annual contests with the Mutual, Athletic and Eureka Clubs have attracted a great deal of attention…The Athletic Club first attracted attention last year by their successful performance as a batting club. They made the best average of any club last season and were only beaten by two teams — the Atlantics and the Actives. Their success this year has been still more marked, and up to the present time they have not met with a single defeat.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, a massive crowd tuned in to see the first game of the three-game set. More than 30,000 spectators showed up for a game that sold 8000 tickets, and in the days before large-scale grandstands — or even fences — were built, they flooded the outfield. In just the second inning, in fact, the game had to be paused for a half hour due to the large number of fans in left field. Since they vacated left field simply by moving into right field, the two teams, “seeing the utter uselessness of the effort to obtain a clear field,” postponed the game.

In what strikes the modern reader as simultaneously deeply prescient and deeply absurd, Philadelphia journalists began condemning the crowd, arguing that two things, gambling and drinking, riled up the crowd and resulted in the game’s cancellation. And yet, at the same time, it was the size and boisterousness of that very crowd that proved the commercial viability of baseball; in fact, the Athletics were able to increase their ticket prices to a dollar per person for the next matchup, four times more than they had for the cancelled game, and they still easily filled the seats.

According to SABR, the series ultimately ended in a tie, due to, of course, that very commercial viability, as both teams squabbled over how to split the series profits. The Athletics hoped to use the profits to pay for the fence they built around the field to help manage the crowd, likely arguing that it was the matchup with the Atlantics that required the fence in the first place; Brooklyn, meanwhile, felt that the fence was Philadelphia’s responsibility and should not come out of their share of the profit. Hey, not only did this series prove that baseball could be economically successful, it predicted the prominent role that gambling and alcohol would play among the fans — and of squabbles about revenue sharing among the owners!