On October 3rd, 2024, Karl-Anthony Towns was traded to the New York Knicks. With only a few weeks left before training camp, there was no way anyone could’ve been prepared for a move of that size or with that timing. And yet, despite that, on October 4th, on 174th and Broadway, there was portly gentleman sporting a Dominicana Towns #32 jersey in all its glory.

Washington Heights, also known as Little Dominican Republic, has gone to bat for a great many of their athletes. However, Andrés Feliz, both

Tito and Al Horford, and Francisco Garcia have all taken a back seat – a third or fourth row seat at that – to the Pedro Martinezes and David Ortizes of the world.

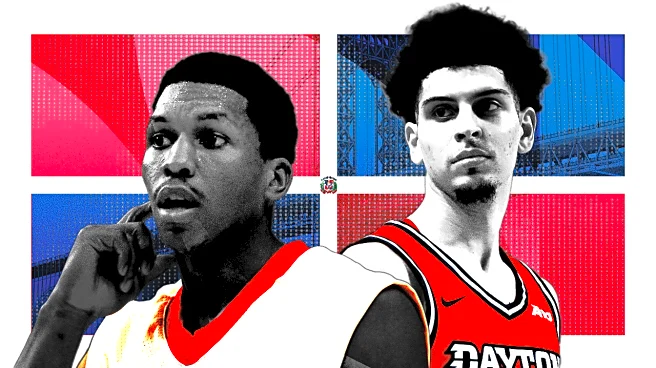

That’s what made a KAT trade so special. For the first time ever, the stars aligned. The best player in Dominican basketball history was suddenly representing the city with the largest Dominican population outside of the DR; a population he had grown up a part of.

German fans followed Dirk Nowitzki to the Dallas Mavericks. Chinese fans went to Houston with Yao Ming. KAT was a Knick. There was no movement necessary.

And yet, on January 19th, I found myself at the Barclays Center watching your Phoenix Suns beat the Brooklyn Nets with all eyes on a player who wasn’t even active. Despite the near 30-point performance from Dillon Brooks, tough shot-making from both Devin Booker and Michael Porter Jr., and two-way showing from Mark Williams, I, along with many others, was there to see rookie guard Koby Brea.

Let me go back a little bit. In 2023, I moved to Washington Heights. Within about two weeks of my move, a friend of mine brought me along to a Men’s Basketball League in the neighborhood.

Being the only non-Spanish speaker in the league came with its own difficulties. Arguing with the ref became an exercise in impromptu translation – to this day, I still think that “yo no entiendo” is still the funniest response to a bad call – and communication came largely through the slow growth of on-court chemistry.

As I showed up more and more, I was embraced as if I had been there for years, not months. I got coached up by the old heads, I was given a nickname (it was in fact stripped from another big man, as the group decided that the actual German kid deserved the title of “el Aleman”), and I was given more and more opportunities to play.

However, when the 2025 NBA Draft was held on the Wednesday night typically reserved for basketball, there was no game to be found. Instead, as I found out later, they were all celebrating a former league mate.

Koby Brea was drafted 41st overall just a day later.

As the story goes, this all started when, at eight years old, Koby’s godfather took him to Gauchos Gym out in the Bronx. Upon being introduced as a shooter, Brea, half the size of everyone else there, made 12 straight threes.

From then on, Koby would be at every game. He would be brought in tow to any number of runs where he would shoot during halftime or free throws. As he became older, he was allowed to play until it was abundantly clear he was too good for the competition. Which brings us to last week’s game.

Everyone had bought their own tickets, and as such, everyone had sat separately. There were small groups dotted around, but the sheer scale of what Koby had listed as friends and family only became clear as the game ended and we made our way to the court.

I have been to a decent number of post-game events. I’ve never quite seen something like this. While security tried to figure out where all these people were coming from, Koby’s father, Stephan, waved us down to the court. The little group of seven or so I was in was followed by another and another until the entire corner of the Nets home floor was filled with nearly thirty designated friends and family. As it turns out, nearly 100 supporters had been there to see him.

Conversations drifted in and out of Spanish but were dotted by frequent and hearty laughter. Waves and waves of people found their way to Brea. “Have you been eating well?” they asked. “You had a concussion, how are you feeling now?” Throughout it all, Koby just kept smiling. It wasn’t the type of smile you wear when stomaching over-involved relatives, nor did it seem like anyone was asking anything of him. He was simply happy to be there with everyone.

It’s a rare thing to get to see players as the people they are. It’s something that the on-court product of the NBA has made near impossible. We, as fans, see these players as the assets they are to our favorite teams. We fall in love with their play, with their development from rookies to vets. We minimize their personalities. Of the 20 odd ratings in 2K, only one of them is about dispositions. Yet, in that moment, I didn’t see Koby Brea, NBA draftee, I saw Koby Brea, just another kid of the neighborhood.

Maybe the Heights aren’t as atypical as that sounds. Every community claims to take care of every child as if they were their own. Still, in an era that has seen the death of the third space and the sterilization of local communities, there is something deeply special about how that one night fought against the idea that individualism and collectivism are at all opposed.

While the rest of New York built upwards, the Heights built outwards, but stayed miraculously close even without the forced proximity.

“A lot of people say their communities are really connected, but I really think there’s something different about Washington Heights,” said a childhood friend of Brea’s. “And I think that interaction with Koby and the fact that other Dominican players who didn’t grow up in the Heights didn’t receive that type of attention, it materializes that love.”

The Horfords are titans of the space as the multi-generational face of Dominican basketball. KAT is probably the best player to ever represent the DR. But, there is a far more fitting historical example of a man who has lived Koby’s story, as the face of the Heights, that comes in the form of his aforementioned godfather.

Felipe Lopez was born in Santiago in 1974, before moving to Washington Heights. He went to high school in Harlem and stayed local for College at St. John’s.

For all intents and purposes, the greatest single athlete to come out of the neighborhood is Alex Rodriguez. During the early 90s, when both Rodriguez and Lopez were high schoolers, it was Lopez who was the bigger draw. The “Dominican Jordan” was the star of amateur New York sports.

“It was very special for me and very special for my community,” said Lopez in an interview in preparation for the 30 for 30 episode about his life titled The Dominican Dream. Behind closed doors, however, he was overcome by the pressure to live up to those standards.

Maybe it was best said by an outsider, as Chris Mullin put it, “I think it goes to a different level when you talk about representing your country. So you’re representing yourself, your family, the Dominican community in New York City, but yet the Dominican Republic—the whole country, so this is added pressure that each and every time you step out there, you got to make a huge statement.”

Felipe Lopez ate himself alive attempting to live up to the burden placed on his shoulders, one that he foisted on himself as much as his supporters put it on him.

Through all of those questions asked of Koby, all of the little needles about diet, travel, health, and whatever else, you know what question was never asked?

“Why didn’t you play?”

Surely, it was at the back of everyone’s minds. While Brea is on a two-way, he has only played in two games this season. After an incredibly impressive Summer League showing, one would expect a larger role.

And yet, no one put that on his plate.

If I’m being completely honest, I don’t think the question of whether Brea sees the floor or not is that important to the people who eagerly shuffled down the stairs at Section 13 to say hello. Even more shockingly to those of us jaded by the internet, I don’t think it’s the status of knowing an NBA player personally either. I think that all the “friends and family” only really cared about one thing: that Koby kept smiling. And that he meant that smile, like he obviously did.

Everybody says their culture is all about food and family. Dominicans are no different. But there’s something special about how big those families get. I had never met his parents. I knew his name as the 41st pick, but I knew nothing about the man. Still, there I was, invited as family to support a player that means so much to so many.

A week later, I was sitting down at a restaurant in Inwood with Koby’s father, invited again as if I was a part of the family. He told me stories of his time organizing and playing in tournaments all across the city, about running Dyckman camps for kids, and the chronicles of his matchups with Stephon Marbury.

He shared memories that I’ve shared in this very piece, things that would be retold again and again at family events. Most notably, he told me about Koby’s little brother. He told me about how the now 12 year old will regularly declare that he will be smarter, stronger, more handsome, and better at basketball than his brother.

When Stephan came back from picking his son up from school, I told him that, “Maybe I’ll be back to interview you in 10 years.” Koby’s brother smiled sheepishly, before nodding his head. He then took a breath and said, “I’m next.”

That seems to be the fundamental truth of basketball. It is so much more than just the sport played by five members of either side over the course of 48 minutes. There is an inherent pressure that we place upon the players we support, a belief that they feel whether through the cheers of the crowd or a more personal message.

With the rise of insincerity and the perpetually online nature of how we all engage with community, we’ve found ourselves in a world where less and less things are real and even fewer are vulnerable. Muse accounts filter genuine fandom through multiple layers of sarcasm and cynicism, hot take culture has sought to polarize everything into either the best ever or fully useless, intimacy in fandom exists only as a way to gain followers and interactions.

And yet, this was the opposite. In a world where player fandoms are usually so synthetic and manufactured, Koby’s were real and organic. So much of the reason that players are not humanized the way they should is because it is simply so hard to find the space to frame them as anything but an athlete. Big players are multi-million dollar brands. Smaller players are harder to cover as anything but a sideshow.

I guess that’s what I’m getting at. We say there’s a whole world behind every person, that every player is someone’s favorite player. Everyone is someone’s hero, someone’s child, someone’s goal. I think we fail to consider just how true that is.

“You get caught up in this grind, and I feel like especially when you have community like that, instead of getting caught up in that grind you learn to just appreciate every single moment and all the individual people that helped you get there…

It’s evident that he takes the time to really sink in it and appreciate how far he’s come…”

Over hundreds of miles and handfuls of years, Koby Brea has made it back home. And I don’t know if there’s a more devoted fanbase anywhere else in the country.