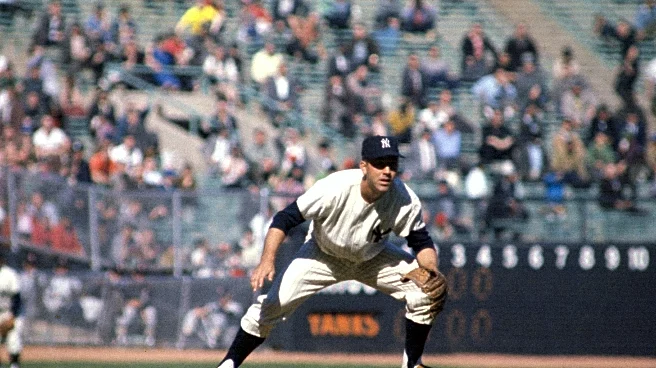

I met Clete Boyer once.

In his later years, Boyer spent summers in Cooperstown, and my family went to see the Hall of Fame once almost every summer in the mid-2000s. We had a running joke about Boyer because every time we went, there was a sign in the downtown that said “Clete Boyer: SIGNING TODAY!” as if it was an unusual event. In 2006, we decided to actually go see him once and ask him to sign a baseball. I was going through a weird phase where I was wearing a different team’s hat every other day,

even though I was a Yankees fan. So for whatever reason, I had an Astros cap on (National League era) when I met Boyer. He tilted his head and said “You’re wearing the wrong hat.”

I didn’t know what to say. And that’s the story of how I basically blew my only opportunity to meet Clete Boyer, probably the best defensive third baseman in Yankees history. So it goes. Boyer was a two-time World Series champion and a valued member of those early-1960s Yankees teams. It’s been quite awhile since they played, but that doesn’t mean memories of them should fade.

Cletis Leroy Boyer

Born: February 9, 1937 (Cassville, MO)

Died: June 4, 2007 (Lawrenceville, GA)

Yankees Tenure: 1959-66

Being one of 14 children born to Mable and Vern Boyer, it was always going to be difficult for Clete to stand out.

The Boyers were raised in the small rural town of Alba, Missouri. Vern Boyer supported his family as a marble cutter. Clete was born during the Great Depression and his family life — like many during that period — was filled with hardship. All but one of Mabel Boyer’s children were delivered at home. As David Halberstam later wrote in October 1964, “the Boyers played hard, worked hard, and accepted life as full of hardship and disappointment.”

Those circumstances did not stop the family from making the most of their opportunities. Remarkably, all seven of the Boyer boys would sign major-league contracts. The oldest, Cloyd Boyer, signed with the Cardinals and broke into the majors as a pitcher in 1949. St. Louis had its eye on the Boyers, as all four of Clete’s older brothers would become Cardinals.

It strangely wasn’t the Cards who ended up signing Clete. It was the Kansas City Athletics, who also employed Cloyd Boyer at the time. The A’s inked Clete to a $35,000 deal on May 30, 1955, and because of his value and due to the “bonus baby” rules at the time, they had to keep the 18-year-old on their big-league roster for two years. Even on a lousy team like the A’s, Boyer wasn’t going to see much time, and he was simply going to struggle against MLB pitching. He hit a dismal .226/.278/.269 with a 47 OPS+ in 114 games during his teenage years bouncing around the infield in K.C.

In the 1950s though, the Kansas City A’s were a Yankees farm club in all but name. Owner Arnold Johnson was well-connected with the Yankees’ ownership group, and he had no qualms about sending his best young players to New York for retreads and cash. There was even a rumor that the Yankees gave Johnson the money to sign Boyer as a future investment since they were over slot in ’55. Sure enough, Boyer ended up in pinstripes in 1957 as a not-so-subtle player to be named later in a preposterous 13-player deal. Following the trade, the Yankees sent Boyer to Class-A Binghamton to find his game, no longer hindered by the “bonus baby” tag.

In Binghamton, Boyer showed power and a knack for the shortstop position. Boyer was promoted to Triple-A in ’58 and continued to show his complete game, batting .284/.353/.494 in 132 games with 22 dingers. Boyer’s big season in Triple-A earned him a spot on the Opening Day roster in ‘59.

Boyer struggled to find playing time behind Tony Kubek at shortstop. And when he did, he simply did not hit. The Yankees smartly sent Boyer back to Triple-A Richmond to find his footing at the hot corner. The work paid off when Boyer was named the starting third baseman. He was a regular in the 1960 lineup, appearing in 124 games and slugging 14 home runs. The Yankees went on to win the AL pennant and Boyer would appear in his first World Series — but not without drama.

What seems to be a common theme among the non-superstar Yankees of the Casey Stengel Era is that his platoon style of managing was overzealous and often rubbed players the wrong way. Game 1 of the 1960 World Series saw much of the same from Stengel. Trailing in the second inning, Stengel pinch-hit for Boyer — in what would have been his first World Series at-bat. Boyer succinctly summed up his feelings on Stengel: “Everybody hated him. When he came out of his mother, the doctor slapped her.”

Boyer had an .833 OPS in his first World Series, but Stengel only used him in four games. The Yankees fell in seven.

Stengel was let go at the end of the 1960 campaign, and replacement Ralph Houk allowed his regulars to play every day. And while Boyer struggled at the plate, his dominant defensive play continued to come into form. His 353 assists at third base led the league in 1961. Yankees second baseman Bobby Richardson once stated “When I made the double play, I could just about close my eyes, put my glove up and the ball would be there.”

The Yankees walked through the AL to another pennant in 1961. Game 1 of the ’61 Fall Classic would take on a much different tone than Boyer’s Game 1 of the previous season. Boyer made two diving plays in that game — proceeding to throw both runners out from his knees. His two incredible plays helped secure a two-hit shutout for Whitey Ford. Ford later said, “No third baseman ever played better than Clete did in the 1961 Series.”

Boyer was now a World Series champion, and he sought to add another ring to his hand in 1962. He put forth what was likely his best season as a Yankee, batting .272/.331/.413 with 18 homers, a 101 wRC+, and 5.1 fWAR. He was at his defensive peak, as great a third baseman as even longtime coach and former player Frankie Crosetti had seen in 30 years.It wasn’t the easiest task hitting in front of pitchers either and finding pitches to hit, but Boyer found a way to get the job done.

The 1962 season also saw Boyer’s finest Fall Classic. It was another seven-gamer, and this time, he played every contest, rewarding Houk’s faith with a .318/.333/.500 line and a homer in the World Series opener:

With the series on the line in the ninth inning of Game 7 in a 1-0 game and Willie McCovey up with the bases loaded against Bill Mazeroski 1960 World Series walk-off victim Ralph Terry, Boyer later admitted that his knees were shaking at third. Fortunately, McCovey’s liner went straight to Richardson’s glove at second, and the Yankees were champions again.

The next two seasons were a regression at the plate for Boyer. He posted an 83 wRC+ in ’63 and a 57 wRC+ in ’64. Boyer still impressed in the field with flashy defense and the Yankees continued to win pennants, but Boyer and the Yankees fell in back-to-back World Series to the Dodgers and then the Cardinals.

Despite the loss for Clete, the 1964 World Series was a special one for the Boyer family, as his hot corner counterpart in St. Louis was his brother, Ken. The soon-to-be-named NL MVP was getting his first taste of postseason baseball and did not disappoint. His offensive game was at its peak, including a series-changing grand slam in Game 4. Clete’s series was not as good, but he did manage a ninth-inning homer off the sensational Bob Gibson in Game 7 to keep the series alive, making the duo the first brothers to ever go deep in the same World Series game.

Clete recalled quietly being happy for his brother once the dust had settled, as he was a terrific player and deserving of a championship ring. Baseball was always a family affair, so it was fitting that this scenario played out for the Boyer family.

Although Clete would never make it back to the World Series, he rebounded in ’65, cracking 18 home runs and posting a 104 wRC+. His production at the plate continued into ’66 but the Yankees were in free-fall. After five consecutive pennants, the Yankees missed the playoffs in ’65 and finished last in ’66. With the new CBS ownership in place and the Yankees going nowhere, the organization decided to move on from Boyer, trading him to Atlanta on November 29, 1966.

Boyer used the motivation of replacing Braves legend Eddie Mathews, the hitter-friendly confines of “The Launching Pad” (then Atlanta Stadium), and the protection of Joe Torre and Henry Aaron helped propel him to a career-high 26 bombs during his first season in the South. He could never repeat his offensive production from his first season with the Braves but put up solid numbers again in ’69. That was a special one for Boyer, who after years of playing in the same league as Brooks Robinson was able to secure his first Gold Glove award. Reflecting on Boyer years later, Torre said, “He came up during the Brooks Robinson era and didn’t get as much attention because of Brooksie, but he could play third base … Great arm.”

In that inaugural season of divisional play, Boyer’s Braves won the first NL West crown (yes, NL West; it’s a long story). However, the “Miracle Mets” swept them away and Boyer could only record one hit in the last playoff series of his career. By 1971, a public feud between Atlanta GM Paul Richards and Boyer was brewing regarding a contract dispute. Richards had slashed Boyer’s salary in 1970 and 1971, with Richards calling Boyer a “sorry player.” The disdain ultimately led to the buyout of Boyer’s contract.

A unique new opportunity arose for Boyer when the Taiyō Whales of Japan’s Central League reached out to him to see if he would be interested in joining them for the ’72 season. With no MLB offers waiting, the 35-year-old Boyer decided to give it a try. It turned out to be a brilliant decision, as he made double what he was making in Atlanta and took advantage of Japan’s cozy parks, averaging 17 homers and a .437 slugging percentage per season during his four years with Taiyo. While they never sniffed the playoffs, Boyer enjoyed his time there and became one of the first former major leaguers to truly embrace Japanese baseball and culture.

Boyer wanted to stay involved with baseball, and he immediately entered coaching, first with Taiyō in 1976 before eventually returning stateside. When Billy Martin became the skipper of the now-Oakland A’s in 1980, Boyer was tapped to be his third base coach, returning to his original franchise. He remained in that role under multiple Oakland managers through ’85. The Yankees hired Boyer first as a minor-league infield instructor, and then to join Martin again in the dugout in ’88, only to find himself out of the job after Martin’s fifth and final Yankees firing.

The Yankees briefly had Boyer managing their Fort Lauderdale club in ’89, and then Stump Merrill had Boyer on his Yankees coaching staff in ’91. When a young Buck Showalter ascended to the Yankees managerial reins in ’92, he made the 55-year-old Boyer his third-base coach to add an older voice to the clubhouse. He was bumped up to bench coach in ’94 before finally stepping away from the rigors of a 162-game coaching schedule. Boyer remained involved with the Yankees organization through 2003 as an instructor and Old-Timers’ Day regular, and then passed away at age 70 in June 2007 due to complications from a stroke.

Thanks again for the autograph all those years ago, Clete. Rest easy.

Editor’s note: Portions of this article have been adapted from former Pinstripe Alley writer Casey Peterson’s far-more-detailed Top 100 Yankees story on Clete Boyer from 2023 and an earlier 2017 edition of the Top 100 that I worked on myself.

See more of the “Yankees Birthday of the Day” series here.