I’ll be honest: I’ve never liked the strategy of not drafting pitchers. I get the risk with injured arms (“TINSTAPP“), but isn’t that what a draft is for? And how many position player prospects pan out,

anyway?

At any rate, this has been a signature of the last two Orioles front office/ownership regimes. Under owner Peter Angelos/GM Dan Duquette, the organization drafted (and evaluated) pitchers badly; as for the David Rubinstein/Mike Elias version, it drafts them rarely and late, if at all.

Maybe this is ultimately good and wise team-building. I don’t know: I’m not a baseball data wunderkind. But, from the perspective of a diehard fan watching from the sidelines, it does result in a team having to buy pitching, whether by trade or free agency. And this, in turn, results in two consequences that we saw in pretty extreme measure during the 2025 season:

- You risk overpaying for top-tier starters, so that “getting a deal” often means settling for mediocrity.

- When you do suffer pitching injuries, your depth of farm-team replacements doesn’t look so good.

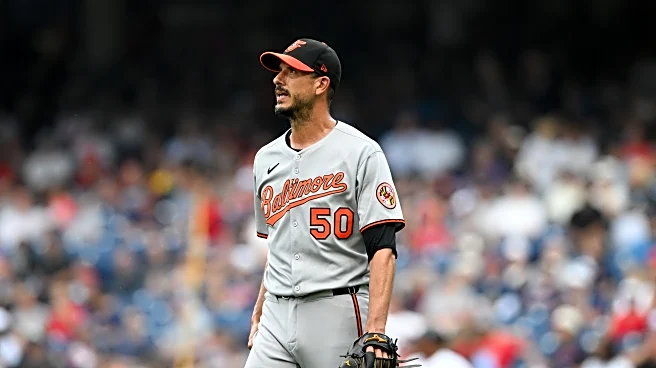

Cue the offseason acquisitions of Tomoyuki Sugano and Charlie Morton. Both came in lieu of multi-year contracts for top-of-the-line starters like Dylan Cease or Garrett Crochet or Max Friend. Both were on one-year deals—the kind of moves that scream “financially prudence” rather than, well, “liftoff.”

Sugano, the Japanese veteran coming over from the Yomiuri Giants, seemed an intriguing gamble: solid NPB credentials, competitive stuff, but the eternal question mark of how that would translate to facing American League lineups. Morton, meanwhile, was a 41-year-old crafty veteran, a pitcher whose résumé included playoff heroics but steadily declining efficiency.

Both were classic “upside plays”: low financial commitment, hope for the best, eat some innings, move on if it doesn’t work out. In retrospect, it seems obvious now, but for a team with genuine World Series aspirations, neither had the necessary upside to push this team to the next level.

Sugano’s season went about as expected. It was… fine. With a 4.64 ERA, 157 ERA, and a stingy 5.1% walk rate, the Japanese righty wasn’t a disaster. He provided durability and kept the team in games. But Sugano didn’t really make the rotation better. He proved a back-of-the-rotation guy, at best.

Morton’s season was bizarre. The highs were really high, as when he started to find the ole curveball again, but the lows were low, and you couldn’t overall say that it was a success. In his first nine starts as an Oriole, he went 0-7 with a 9.38 ERA, getting hit so hard every start it was hard to watch. That included allowing seven runs in just four innings in the infamous 24-2 loss to Cincinnati, the Orioles’ worst since 2007. Then, amazingly, he put together a run of brilliance, with a 2.37 ERA and 11.9 strikeouts per game over a dazzling six-game stretch. And then, poof, he was traded, and retired soon thereafter.

It’s easy to play the Monday morning quarterback here, but with the clarity of hindsight, was either of these signings—a veteran command artist in Japan who’d never struck out a lot of people and a 41-year-old with a nice curveball and odds-defying longevity— the thing that would push the Orioles to deep-in-the-playoffs relevance?

At the end of the day, the Orioles ended up with the third-worst rotation in the American League, averaging a 4.65 ERA and more home runs surrendered than any outfit Colorado, the Blue Jays and the Athletics. This was, as has been much discussed, poorly timed. The Orioles, blessed with one of baseball’s most talented young cores, won 101 games in ’23 and 91 in ’24, and then they approached the pitching market in ‘25 like they were bargain hunters at a clearance sale.

And then there’s the organizational depth issue. In fairness to the team, they suffered more from injuries than most. But when injuries struck, well, the cupboard wasn’t bare, but it certainly wasn’t stocked with MLB-ready arms who could step in and hold down a rotation spot. This is partly the reason the team used 38 pitchers over the season (not counting position players who got thrown into the line of fire like Jorge Mateo and Gary Sánchez), including people like Cody Poteet, Shawn Dubin, Carson Ragsdale, Matt Bowman, Scott Blewett, Corbin Martin… I could go on.

This, it seems to me, is the natural consequence of the no-pitchers-in-the-draft philosophy. You can’t develop what you don’t draft, and you can’t call up impact pitching prospects you never acquired.

To be fair, the front office didn’t completely ignore pitching development in 2025. The midseason trades brought in some arms with potential—primarily relief prospects and lower-level starters who project as organizational depth rather than impact pieces. These acquisitions might fill out Norfolk’s roster nicely, although none of them screamed “future ace” or even “reliable third starter.” Similarly, the 2025 draft saw the Orioles finally select some pitchers, including lefty Joseph Dzierwa in the second round and righty JT Quinn as a competitive balance pick, both college arms with projectable frames. Maybe one or two will surprise us. That said, they’ll do so maybe in 2028, not for a team trying to win in 2026.

Which brings us, like a lot of recent writing on the Orioles, to Pete Alonso. The blockbuster signing of the slugging first baseman signals, probably, that the Orioles ownership group finally decided that being competitive isn’t enough. Championship windows don’t stay open indefinitely, and Gunnar Henderson, Adley Rutschman, and Jackson Holliday aren’t going to be cheap forever. The Alonso deal seems to say, “We’re willing to spend real money to win now.”

The question is whether that same all-in mentality will extend to the pitching staff. If the lesson from 2025 is that you can’t bargain-hunt your way to elite starting pitching, then the offseason demands action. Whether that means breaking the bank for a frontline starter or aggressively pursuing trades for controllable young arms, the strategy of Morton-and-Sugano-style stopgaps has been definitively proven insufficient. The Orioles learned an expensive lesson in 2025: you can’t half-commit your way to a World Series. The Alonso signing suggests they’ve internalized that message. The real test is whether they’ll apply it where it matters most—on the mound.