When a future Hall of Famer signs a 10-year deal to join a new team, that contract is usually remembered first and foremost for how that player performs on the field. Over that length of time, an elite talent will generally put up the types of numbers and generate the types of iconic moments that endear him to a fanbase forever, making him inextricably linked to the franchise that shelled out the cash to bring him aboard.

Dave Winfield hit .290 with 205 home runs during his nine years in New York,

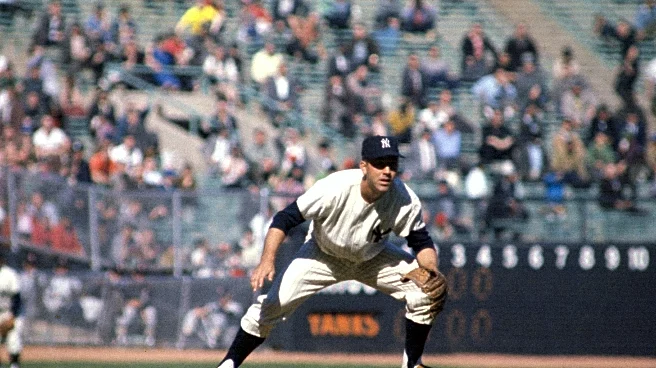

ranking 11th in slugging percentage and seventh in long balls in the club’s storied history by the time he departed. He garnered five Silver Sluggers and as many Gold Gloves while in pinstripes, and received MVP votes in six seasons. And yet, his tenure is best remembered for the contract he signed to join the Yankees itself — and that contract’s fallout, which extended well into the next decade.

Dave Winfield

Signing Date: December 15, 1980

Contract: 10 years, $23 million

Dave Winfield was always an outlier. During his time at the University of Minnesota, he led the school to a Big Ten basketball championship and won MVP of the College World Series, largely on the strength of his dominance as a pitcher. Taken in the MLB, NFL, and NBA drafts, Winfield opted to sign with the Padres, who took him fourth overall in 1973. The 6-foot-6 prodigy was assigned directly to San Diego, bypassing the minor leagues altogether, and he started to rake right out of the gates. In all, he spent eight years with the Padres, steadily improving until a breakout 1979 that saw him lead the league in bWAR (8.3), RBI (118), and OPS+ (116) while taking home his first Gold Glove Award.

When he declared free agency after the 1980 season, the 29-year-old was positioned for a major payday. Yankees owner George Steinbrenner came calling, inking Winfield to a 10-year, $23 million contract that was then the most expensive contract in the history of professional sports. The fact that the superstar didn’t sign until December 15th, commonplace nowadays, was characterized as an “odyssey” by The New York Times, underscoring the high-profile nature of the bidding war, which included the Mets and Cleveland as well. “The Yankees’ offer was definitely not the highest I received,” Winfield said at the time, emphasizing that the potential to play for the people of New York and compete for a championship drove his decision. The historic compact was announced at a press conference with stars Willie Randolph and Reggie Jackson as well as Steinbrenner on hand, signaling a changing of the guard for the Yankees.

There was just one problem. Steinbrenner understood the contract to be worth $16 million, apparently failing to notice a cost-of-living clause included by the Winfield camp that would raise the outfielder’s salary by 10 percent each year. That mix-up would cost the Yankees’ owner $7 million — and, in due time, much more.

In his first season in pinstripes, despite being limited to just 105 games, the $23 million man was nonetheless as advertised, slashing .294/.360/.464 and finishing seventh in MVP voting. He hit .350 in the Division Series against Milwaukee, playing a crucial role as the Yankees eked out a narrow three-games-to-two victory. After sweeping Oakland in the ALCS, the stage was set for Winfield to play hero as he made his first World Series appearance in just his first season with New York.

That’s where the fairytale ended. Winfield got a single, solitary hit in 27 plate appearances, floundering under the game’s brightest lights. He was far from the only reason the Yankees lost in six games to the Dodgers — Reggie Jackson and Graig Nettles were each limited to three games by injury — but he became the focal point for the frustrating defeat. Steinbrenner would come to label his new star “Mr. May,” a derisive nickname drawn in contrast to Jackson’s “Mr. October.” He would repeat the cruel moniker repeatedly in the years to come, as Winfield would never get the chance to redeem himself in another postseason run with New York.

That’s not to say his time there was a failure. The outfielder earned All-Star selections in each of his first eight years with the club while delivering defense at the outfield corners that, while questionable by modern metrics, was enough to net him five Gold Gloves with the Yankees.

Perhaps his best campaign came in 1984, when he hit .340 with a 154 OPS+, narrowly losing the batting title to his teammate, Don Mattingly. The pair formed a dynamic duo through the end of the ‘80s and, while the Yankees never again reached the playoffs during that time, they were hardly bottom-feeders either, ending the decade with more wins than any other team.

After missing the entire 1989 season with a back injury, Winfield returned the following year, the last of his 10-year deal. The 38-year-old was relegated first to DH duty and then to the short side of a platoon against left-handers as he began to get phased out of the Yankees’ offense. On May 11th of that season, general manager Pete Peterson and manager Bucky Dent delivered an impromptu press conference at Seattle’s Kingdome announcing their superstar had been traded to the Angels. There was just one problem — Winfield, who had inserted himself into the scrum without receiving an invite, indicated he had no interest in leaving and would not sacrifice the no-trade clause he’d earned through playing at least 10 years in the league and at least five with his current club. “I’m not going anywhere; I’ll make the choice when and where and how I go,” he told a stunned press, who had a field day with the dysfunctional scene. Ultimately, Angels owner Gene Autry offered Winfield a three-year, $9.1 million extension, at which point he acquiesced and accepted the trade.

While this drama was playing out publicly, a more shocking one was playing out behind closed doors. MLB Commissioner Fay Vincent was in the midst of an investigation into a payment Steinbrenner had made to Howie Spira. The mobbed-up grifter, who was working with Winfield’s David M. Winfield Foundation for Underprivileged Youth as an unpaid publicist, had approached the Yankees’ owner with an offer of dirt on his star outfielder in exchange for a payoff. Steinbrenner paid Spira $40,000 for the information, presumably in hopes of using it to damage Winfield’s character in the public eye and roll back some of his contractual obligations to the slugger, which included payments to the non-profit. “The Boss” never received that dirt and got slapped with a lifetime ban on July 30, 1990, ending his active involvement with the Yankees. He would end up reinstated in 1993, and many credit Gene Michael’s stewardship of the team in Steinbrenner’s absence (and without the influence of his heavy hand) as a primary reason for the dynasty to come.

For his part, Winfield had the last laugh. He was a man reborn in California, hitting 19 homers in 112 games the rest of the 1990 season to take home Sporting News Comeback Player of the Year honors. He spent one more year with the Halos before his last hurrah, a magical 1992 with the Blue Jays. Winfield slashed .290/.377/.491 with 108 RBI in his age-40 season. More crucially for the man derided as “Mr. May,” the veteran finally got his World Series ring, knocking in two via an 11th-inning double against Charlie Leibrandt in the decisive Game 6 in Atlanta to give Canada its first title.

Winfield spent three more years in baseball, becoming the 19th player to collect 3,000 hits,which he accomplished during a stint with his hometown Twins.

He was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2001, his first year of eligibility, and went in as a Padre despite spending the bulk of his career in New York.

Winfield and Steinbrenner had something of a rapprochement as the years went on, with Steinbrenner expressing contrition around the time his former player was inducted. “He said things that made me believe he regretted what had happened,” Winfield would later say. Winfield participated in multiple ceremonies in 2008 surrounding the end of old Yankee Stadium, by which point Steinbrenner was a shell of his former self. “When you see a strong, robust man like him, and now that persona has totally changed, you just can’t help but look at someone differently,” Winfield told Bob Costas in ‘08. “Maybe there are things that never get forgotten, but you just can’t help making it bygones.”

In recent years, Winfield has become an elder statesman of the game, championing Negro League players and helping baseball provide an avenue for normalized relations with Cuba while working with younger players through the MLB Players Association. To the extent that his tenure in New York is remembered for his warring with Steinbrenner, Winfield should be remembered for the grace and tenacity he showed when confronted by a capricious heavyweight. And, for those who watched the future Hall of Famer play in pinstripes — including Derek Jeter, who grew up with a poster of Winfield on his wall — his talent and production surely overshadowed everything else.

See more of the “50 Most Notable Yankees Free Agent Signings in 50 Years” series here.