In the 1850s, thousands of immigrants from the Bohemia region of Czechoslovakia settled in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Most of these immigrants settled into neighborhoods just southeast of downtown and worked at local meatpacking plants. Two of those new Americans were Frank and Sofia Slapnicka. The Slapnickas had four children; the youngest, named Cyril, soon developed a fascination with American sports.

The area settled by those immigrants is still rich with history. On the north side of the Cedar River

sits Little Bohemia. If you cross the 12th Avenue bridge, you’ll find yourself in The Czech Village. Both neighborhoods are rich with shops, bars, restaurants, and museums.

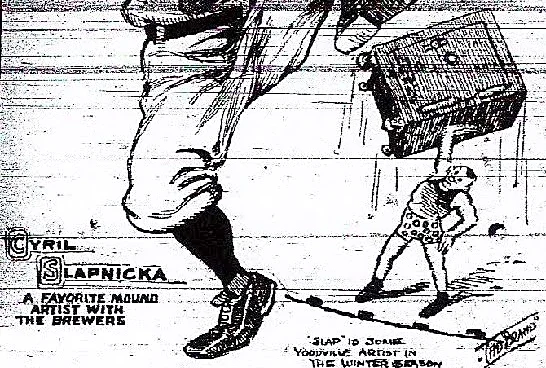

Slapnicka, known as “Slappie,” was a right-handed pitcher who could also switch hit. His fastball was nothing to write home about, but he did possess a wicked curveball. In 1906, at the age of 20, Slappie signed with the Marshalltown Brownies of the Iowa League of Professional Baseball Clubs. It’s amazing to think about how different baseball was in those early years. The major leagues were not nearly as popular as they are today. Every town and village had a ball club linked together by a regional league. Occasionally, a young star would appear (think Roy Hobbs) and the town team would sell their prodigy to a larger club or sometimes sell their young star directly to a major league club.

Slappie, despite his love for baseball, was not a star. He spent the next six seasons kicking around various Class C and Class D leagues in the Midwest. Besides Marshalltown, he played for Burlington, Joplin, Rockford, and Hannibal. I love the names of some of these teams. Joplin was the Miners, which makes sense given the mining history of that region. Burlington was named the Pathfinders. Rockford, which was an affiliate of the Chicago Cubs, was first the Reds, before switching to the awesome-sounding Wolverines. The best (most controversial?) name was for the Hannibal team, which went by the Cannibals. Hannibal Cannibals.

After a sparkling 1911 season in which he went 26–7 for Rockford (Wolverines, not the Reds), Slapnicka was called up to the Cubs. He made his major league debut on September 26, 1911, against the Boston Braves in a game played at Wrigley Field. Slappie took the loss that day, by the score of 7–5, after throwing eight innings. He appeared in two more games that season, throwing eight innings of two-hit relief against the Pirates and another eight innings in a 4–3 loss to the Reds, which was played at the wonderfully named Palace of the Fans in Cincinnati.

The Cubs optioned Slapnicka to Louisville in January 1912. The Louisville club soon sent Slappie to Milwaukee of the American Association, where Slapnicka spent the next six seasons. Those Milwaukee teams were also known as the Brewers and played at iconic Borchert Field, which was located just north of downtown. Slapnicka became something of a folk hero in Milwaukee, both for his pitching and for his extracurricular activities. The local press called him the Athenian Prince or the Grecian Blonde. To make ends meet, Slapnicka began a career as what can best be described as “a vaudeville entertainer.” He performed as a strongman, an acrobat, and a juggler. According to the Milwaukee paper, Slapnicka developed quite a reputation as a talented acrobat and would juggle anything he could lift. He would stack three tables on top of each other, then stack three chairs on the tables, and somehow manage to balance himself on the top chair. Slappie’s show played at the Empress Theatre in downtown Milwaukee. The Empress, of course, is long gone. Today that location holds a Courtyard by Marriott.

Milwaukee made Slappie give up his entertainment career, fearing injury to his arm. In response, Slapnicka bought a bar—or in the parlance of the times, what was generously called a saloon. Locals began calling it Slapnicka’s Booze Emporium.

The fun ended when Milwaukee sold Slapnicka to Birmingham of the Southern Association prior to the 1918 season. When the Southern Association suspended operations in June, Slappie’s contract was purchased by the Pittsburgh Pirates. Seven years after making his major league debut, Slappie was back in the big time.

He made his first start on July 2, then picked up his first and only major league win on July 5, when he tossed a complete game against the New York Giants at Forbes Field. Slappie appeared in five more games that summer, throwing a total of 49 innings with an ERA of 4.74.

After the season ended, the Pirates sold Slappie’s contract back to Birmingham. He closed out his career in 1920 with his hometown Cedar Rapids Rabbits of the Illinois-Indiana-Iowa League.

In 1919, Slapnicka discovered his true calling when he convinced Birmingham (which was an affiliate of the Detroit Tigers) to take a look at another young Cedar Rapids pitcher, Earl Whitehill. Birmingham signed Whitehill, and by 1923, Whitehill was in Detroit, where he quickly became a star. Over his 17-year career, Whitehill won 218 games.

When Slappie’s career as a player ended, he seamlessly morphed into being a scout. Slapnicka had a great eye for talent and over his career as a scout signed such luminaries as Hugh Alexander, Lou Boudreau, Gordy Coleman, Jim Hegan, Ken Keltner, Roger Maris, Herb Score, Hal Trosky, Bill Zuber, and most famously, Bob Feller.

In those wild and woolly days, teams would often “hide” a young star in the minors. Players’ rights were virtually non-existent, and teams (and scouts) often used creative methods to secure a player they desired. This brought Slapnicka into the wrath of baseball commissioner Kennesaw Mountain Landis on several occasions.

In a case that is legendary in the state of Iowa, Slapnicka signed Bob Feller when the youngster was 16 years old for $1 and an autographed baseball. Feller, who had a rocket launcher attached to his right shoulder, was coveted by several other teams who complained vigorously to the righteous Landis about Feller’s contract. Young Robert and his father were interviewed by Landis, and they both insisted that Bob stay with the Indians. Landis allowed it after the Indians agreed to pay the Des Moines baseball club $7,500, which was a lot of money in 1936. Slapnicka would go on to be Feller’s business manager and in many ways a father figure to Feller.

Landis didn’t always bend to the Indians. In 1936, Cleveland was trying to hide a terrific young infielder named Tommy Heinrich at their Class A New Orleans farm team. Heinrich hit .346 at New Orleans and, after only getting a promotion to AA, complained to Landis. Landis declared Heinrich a free agent when several teams said they’d play him immediately. Cleveland lost the bidding to the Yankees, and Heinrich went on to be a five-time All-Star while playing on six World Series championship teams.

Slappie rose to the position of General Manager of the Indians, but after suffering a heart attack in 1938, stepped away from baseball. He returned in 1942 as a scout for the St. Louis Browns and followed that up with stints with the Cubs and a second go-around with the Indians. He stayed with Cleveland until the end of the 1960 season, retiring at the age of 74.

In retirement, Slapnicka returned to his beloved Cedar Rapids. He passed away on October 20, 1979, at the age of 93. Herb Score, whose once-promising career was cut short by injury, said of Slappie: “When you’re talking to the man that signed Bob Feller, and he’s interested in you, you pay attention.”