The Quarterback Crisis Nobody Wants to Confront

There has never been a time in NFL history when quarterbacks entered the league with more physical tools. Arm strength is stronger, size is bigger, speed is faster, and athleticism is off the charts. Every draft class seems to produce a new wave of prospects who can throw the ball 70 yards in the air and outrun linebackers in space. On paper, this should be the golden age of quarterback play.

Instead, the opposite has quietly become true.

Sustained excellence at the position has become increasingly

rare. Rookie success is often fleeting. Second-year regression has become almost expected. Teams cycle through quarterbacks at an alarming rate, burning high draft picks on players who look promising early and are exposed just as quickly. The league is full of talented passers, yet remarkably short on quarterbacks who can consistently diagnose defenses, control games late, and perform at a high level when structure breaks down.

This is usually framed as an individual problem. The quarterback “wasn’t good enough.” He “couldn’t process fast enough.” He “didn’t develop.” But when the same pattern repeats across draft classes, systems, and franchises, the issue stops being individual and becomes structural. This is not a coincidence. It is the product of a developmental pipeline that is no longer aligned with what the NFL actually demands from its quarterbacks.

The modern quarterback arrives in the league more physically prepared than ever. He just arrives far less intellectually prepared for the job he is being asked to do.

College Football Didn’t Evolve — It Simplified

The foundation of this problem begins in college football.

Over the last fifteen years, the sport has undergone a near-universal shift toward spread offenses. What was once a landscape of mixed systems — pro-style, West Coast, option, power, and spread — has become almost entirely dominated by one philosophy. RPO-heavy designs. Half-field reads. First-read concepts. Quick game built to get the ball out immediately. Offenses structured to minimize mental load rather than expand it.

This shift is often described as evolution. In reality, it is simplification.

College offenses are no longer designed primarily to teach quarterbacks how to read defenses. They are designed to make quarterbacks functional as quickly as possible. With the rise of the transfer portal and the acceleration of recruiting and NIL, coaches no longer have the luxury of building multi-year developmental tracks. Quarterbacks arrive and are expected to start immediately. Transfers arrive and must be playable in weeks, not years. Freshmen are promised playing time before they ever take a college snap and coaches must follow up on that promise as schools put millions into these freshmen.

In that environment, complexity becomes a liability.

Systems must be installable quickly. Reads must be simple. Progressions must be shallow. The goal is no longer to develop a quarterback over three or four seasons, but to extract production as fast as possible before the roster changes again. The result is an entire generation of quarterbacks who are highly efficient within a simple structure, but rarely asked to command it or evolve in it.

Transfer Portals, Roster Chaos, and the Death of Progression

The rise of the transfer portal didn’t just change where quarterbacks play. It changed how quarterbacks are taught.

In previous eras, continuity was assumed. Quarterbacks stayed in the same system for multiple seasons. Coaches layered complexity year by year. Protections became more advanced. Pre-snap responsibilities expanded. Progressions became deeper. By the time a quarterback reached his third or fourth season, he was not just more experienced — he was more educated. He had failed, adjusted, learned, and grown within the same framework.

That model no longer exists.

Quarterbacks now move frequently. Offensive coordinators change constantly. Playbooks are rewritten annually. Systems are built not for long-term mastery, but for immediate usability. A quarterback who transfers in January must be playable by September. A freshman who arrives in June may be starting by October. In that environment, there is no room for layered development. Everything must be installable quickly, understandable immediately, and executable with minimal mental burden.

As a result, systems are frozen at an introductory level.

Instead of progressing intellectually from year to year, many quarterbacks simply repeat the same mental workload with different terminology. They get older. They get stronger. They get faster. They do not get more sophisticated.

Modern quarterbacks aren’t progressing through the educational levels of the position — they’re staying in Grade 4 longer, rather than advancing through Grade 5 and Grade 6 before being dropped directly into Grade 7, which is the NFL.

That gap is not theoretical. It is structural.

College football rosters are older than ever, filled with fifth- and sixth-year players. Yet quarterback education is more stagnant than it has ever been. Players are spending more time repeating the same lessons rather than advancing to harder ones. The position is aging physically while remaining young mentally.

The NFL, meanwhile, still expects them to arrive ready to skip multiple levels of complexity instantly.

That gap is the beginning of everything that follows.

College Defenses Are Simplified Too — And That Matters

One of the most common rebuttals to this argument is that college defenses are better and faster than they used to be. That is partially true — athletically. It is not true structurally.

Just as offenses have been simplified to accommodate constant roster turnover, defenses have been simplified for the same reason. College football today is built around freshmen, sophomores, and transfers learning new systems every year. Complex disguise packages, layered pattern-matching coverages, and advanced pressure schemes require continuity, repetition, and shared experience. Most programs no longer have that luxury. The days of the complex Nick Saban match zone defenses are mostly gone.

As a result, many college defenses are designed to be installable quickly rather than deceptive deeply.

You still see athletic edge rushers. You still see fast linebackers. You still see talented corners. What you rarely see is sustained post-snap rotation, late safety movement, or defensive structures designed to actively manipulate a quarterback’s eyes. Coverage tends to declare early. Blitzes are often honest. Rotations are predictable. The quarterback is rarely asked to hold a picture in his head from pre-snap to post-snap and adjust in real time. This matters more than speed.

A quarterback can handle faster players. What he cannot handle without training is uncertainty.

In the NFL, the primary challenge is not arm talent or velocity. It is the ability to process moving information after the ball is snapped. Late-rotating safeties or simulated pressure. Coverage that shows one thing and becomes another. That skill is learned only through exposure. Most modern college quarterbacks simply do not get it.

They are dominating defenses that are simplified in the same way their offenses are.

And that is why the transition is so violent and that will only worsen.

The Illusion of College Dominance

College quarterback evaluation has become increasingly deceptive because the environments in which quarterbacks succeed are increasingly artificial.

At the top level, elite programs spend a large portion of the season playing opponents with little NFL talent. Even in conference play, the disparity between the top and middle of a league can be massive. Quarterbacks often face only a handful of defenders across an entire season who will ever play meaningful snaps in the NFL.

This is not just about competition level. It is about problem frequency.

Elite college quarterbacks are rarely forced into repeated chaotic situations. They operate behind dominant offensive lines. They throw to receivers who are often superior athletes to the defenders covering them. They play in systems designed to manufacture space. There are games where a quarterback can go entire halves without being touched.

That is not preparation, but rather that is insulation.

In the NFL, there is no insulation. Every opponent has NFL pass rushers. Every secondary disguises coverage. Every linebacker can run. Pressure is not occasional — it is constant. Windows are not wide — they are tight. Solutions are not given — they must be created.

College dominance often reflects environment more than readiness.

A quarterback can look extraordinary in a setting where problems are rare and controlled, then look overwhelmed when problems arrive on every snap. That is not a failure of talent. It is a failure of preparation.

College Football Used to Prepare Quarterbacks for the NFL

What makes this entire shift more troubling is that it is not inevitable. College football did not always operate this way.

For years, some of the most successful programs in the country ran offenses specifically designed to prepare quarterbacks for the NFL. Alabama did it under Nick Saban. Stanford did it with Andrew Luck and others. Michigan did it for years in the late 2000s and 2010s. In the 1990s, most systems were Pro-style. These were not gimmick systems. They were demanding, pro-style offenses built around full-field progressions, under-center work, complex protection schemes, and real pre-snap responsibility.

Quarterbacks in those systems were not just executing plays. They were learning how to run an offense.

Andrew Luck did not step into the NFL and slowly learn how to process defenses. He did it immediately, because he had already been trained to. He had adjusted protections. He had changed plays. He had manipulated safeties. His education translated.

That pipeline worked.

It was not abandoned because it failed. It was abandoned because the incentives of college football changed.

Pro-style offenses are difficult to install. They require time. They require patience. They require quarterbacks to struggle before they succeed.

Modern college football no longer allows for that.

The result is a generation of quarterbacks who arrive in the NFL with more athletic ability than ever — and less experience doing the actual job than any generation before them.

Failure Was Removed From the Learning Process

One of the most damaging consequences of modern college offenses is not what they teach quarterbacks — it is what they no longer allow quarterbacks to experience.

Failure has been engineered out of the learning process.

RPOs, bubble screens, quick slants, and packaged plays are designed not just to create efficiency, but to eliminate negative outcomes. The quarterback is rarely forced to live with a bad decision because the system is built to avoid the moment where a bad decision could even occur.

This creates efficient production. It does not create resilient quarterbacks.

In previous eras, quarterbacks were allowed — and expected — to fail. They threw interceptions. They misread coverages. They checked into the wrong protection. And then they were forced to correct those mistakes within the same game, the same system, and the same conceptual framework. Failure was not avoided. It was taught through.

Modern quarterbacks arrive in the NFL having rarely had to recover from repeated adversity within a drive, let alone within a season. When the first read is gone, when the RPO is taken away, when the screen is covered, many of them have no internal framework for what comes next.

In the NFL, failure is not occasional. It is constant.

Quarterbacks who have never been taught how to process failure are suddenly asked to survive it.

Snap-to-Throw Speed Has Become a Crutch

Another modern misconception is that fast decision-making equals advanced processing.

In college football today, many quarterbacks are praised for how quickly the ball leaves their hands. The metric is snap-to-throw time. The evaluation becomes speed. The assumption becomes intelligence.

But speed does not necessarily mean understanding.

In many spread systems, the quarterback is not making a decision at all. The decision has already been made for him. The ball is thrown to a predetermined receiver based on a pre-snap look. The read is binary. The progression is shallow. The throw is quick because the thinking is minimal.

NFL defenses are acutely aware of this.

They design pressures and coverages specifically to bait quick throws. They disguise leverage. They show false blitzes. They rotate late. They force quarterbacks to hold the ball for an extra half-second — just long enough for processing flaws to surface.

This is where many modern quarterbacks are exposed. They are fast throwers, but they are not fast thinkers.

When the first answer is taken away and the second answer is disguised, they do not slow down and diagnose. They hesitate. They drift. They scramble. Or they make the wrong throw.

The problem is not arm talent. It is not accuracy. It is that the quarterback has never been trained to live in uncertainty.

The NFL Shock: From One-Read Comfort to Full-Field Warfare

This is the moment where everything breaks.

In college, many quarterbacks operate in controlled environments. Half-field reads. Defined leverage. Declared coverage. Protection that holds. Space that exists. Time that is available.

In the NFL, none of that is guaranteed.

The quarterback is suddenly responsible for full-field progression. He must diagnose coverage after the snap, not before it. He must adjust protections. He must identify simulated pressure. He must understand how one defender’s movement changes the entire structure of the defense.

And he must do it while faster, stronger athletes collapse the pocket on every snap.

Even great offensive lines do not eliminate pressure in the NFL. They merely delay it. Every week, quarterbacks face edge rushers who can win in under two seconds.

This is not a higher degree of difficulty. It is a different job entirely.

Quarterbacks who spent their college careers solving simple, stable problems are now asked to solve complex, moving ones. They are not failing because they lack courage or work ethic… they are failing because the job they are being asked to do is fundamentally different from the one they were trained for.

This is the shock that defines modern quarterback development.

The Lost Art of Letting Quarterbacks Sit

For much of NFL history, sitting a young quarterback was not controversial. It was considered responsible.

Carson Palmer was the first overall pick and did not start a game as a rookie. Aaron Rodgers sat for three full seasons behind Brett Favre. Philip Rivers sat for two years before taking over in San Diego. These were not fringe prospects. They were franchise-altering players, and teams still believed that exposing them too early was more dangerous than delaying their debut.

Even as the league modernized, that philosophy persisted. Patrick Mahomes sat an entire season behind Alex Smith. Josh Allen did not take over immediately in Buffalo. Lamar Jackson was brought along slowly and did not become the full-time starter until midseason. These players were allowed to learn the language of the NFL before being asked to speak it fluently.

Sitting was not a punishment. It was part of the curriculum.

There is also a psychological layer to this that often gets ignored. As someone who has trained quarterbacks, I can tell you that confidence at the position is not a renewable resource. It is fragile. When it is built carefully, it compounds. When it is broken, it rarely comes back to the same level.

Quarterbacks do not just fail mechanically. They fail mentally.

Once a quarterback begins to anticipate pressure, hesitate on throws, or question what he is seeing, that damage lingers. The position is built on trust — trust in your eyes, your timing, your protection, and your decision-making. When that trust is shaken early, it alters how a quarterback plays permanently.

Carson Wentz is one of the clearest modern examples of this. He was an MVP-caliber quarterback in 2017. He tore his ACL, rushed back into an unstable environment, struggled, lost confidence, and within two years was traded. The physical injury healed. The quarterback never fully did.

That is the risk of throwing raw players into the fire.

Young quarterbacks were once protected not just from defensive complexity, but from themselves. They were allowed to struggle privately before they were asked to perform publicly. By the time they were handed the job, they were mentally prepared for what the job demanded.

That layer of protection is now almost entirely gone.

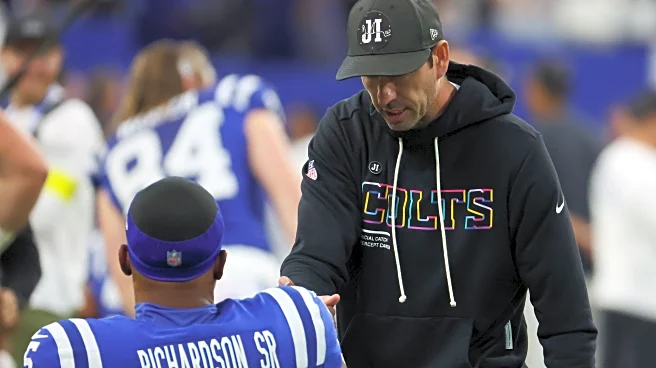

Today, raw quarterbacks are drafted and thrown into the lineup immediately. The Colts saw this firsthand with Anthony Richardson. They are expected to learn by failing on Sundays, under national scrutiny, against the fastest and smartest athletes in the sport. The idea of protecting a quarterback from himself has been replaced by the idea that the only way to learn is to play.

For quarterbacks who arrive underprepared, that is not development, but rather, it is damage and career altering.

Why That Patience Disappeared

The disappearance of patience in quarterback development was not accidental. It was driven by a series of structural pressures that now dominate the league.

The rookie wage scale created urgency. Teams now have a short window where quarterbacks are cheap and rosters can be built around them. Coaches feel pressure to extract value immediately before that window closes. Owners want to see a return on their investment. Fans demand instant results. Media scrutiny is relentless.

At the same time, coaching job security has evaporated.

Few head coaches or offensive coordinators can afford to spend two years developing a quarterback without wins to show for it. The incentive is no longer to build slowly. It is to produce quickly, even if that production is fragile.

College tape makes this easier to justify. Spread systems make quarterbacks look ready. High completion percentages and gaudy numbers create the illusion of preparedness. Teams convince themselves that this quarterback is different, that he can skip steps, that he will learn on the fly.

Sometimes they are right. Most of the time, they are not.

Raw quarterbacks are placed into starting roles before they have learned how to survive the job. When they struggle, the conclusion is that the player failed, not that the process failed. The league moves on to the next prospect and repeats the cycle.

The development window did not shrink because quarterbacks got smarter. It shrank because the NFL stopped being willing to wait.

Early NFL Success Is Often a Mirage

This is where modern quarterback evaluation becomes most dangerous.

In recent years, several young quarterbacks have found immediate success in the NFL by stepping into systems that mirror what they ran in college. Spread formations. RPOs. Quick game. Screens. Defined reads. Offenses built to give the quarterback easy answers.

It works — at first.

Defenses are cautious early. Coordinators do not have tape. Tendencies are not yet exposed. The quarterback plays fast and confident, and the league rushes to declare him a star. We saw this with CJ Stroud, Jayden Daniels and others.

Then the adjustments come.

Defensive coordinators identify patterns. They disguise leverage. They take away first reads. They force the quarterback to win from the pocket on third down, in tight windows, with full-field progression.

This is the moment that separates execution from mastery.

We have seen this cycle repeatedly. Early success. Late-season regression. Offseason doubt. New coordinator. New system. Restart.

When offenses are copy-pasted from college, they create immediate production. They do not create durable quarterbacks.

That is why coordinators are fired so quickly. That is why second seasons are often harder than first ones. That is why so many young quarterbacks peak early and plateau.

The early success was not proof of readiness. It was proof that the system worked.

The Shrinking List of Quarterbacks Who Actually Sustain Success

When you step back and look at the modern NFL, the most telling evidence of this developmental problem is not how many quarterbacks enter the league.

It is how few remain.

Every year, the draft produces a new wave of highly touted prospects. Every year, several of them flash early. Every year, the league rushes to declare the next generation has arrived.

And every year, most of them fade.

If we define true success not as one good season, but as sustained regular-season excellence combined with consistent playoff performance, the list becomes shockingly small.

Patrick Mahomes

Josh Allen

Joe Burrow

Matthew Stafford

You can argue for Jared Goff. You can argue for Dak Prescott. But even those cases are complicated by postseason struggles and system dependency. Many others would say Lamar Jackson, but his performances in the playoffs lead a lot to be desired.

Now look at the draft years.

Mahomes: 2017

Allen: 2018

Stafford: 2009

Goff: 2016

Prescott: 2016

Burrow: 2020

Almost all of the quarterbacks who have proven they can both carry teams in the regular season and survive the postseason pressure were drafted before 2018, with Burrow as the lone recent exception.

Meanwhile, the league has cycled through:

Justin Herbert

Tua Tagovailoa

Trevor Lawrence

Jalen Hurts

Mac Jones

Zach Wilson

Trey Lance

Anthony Richardson

Bryce Young

CJ Stroud

WIll Levis

Some have had good regular seasons and put up great numbers.

Very few have proven they can consistently solve playoff defenses.

This is not coincidence.

This is the consequence of a development pipeline that produces quarterbacks who can execute systems, but not command games.

Time to thank their NFL Coaches; Products of Systems, Not Masters of Defenses

This is where modern quarterback evaluation becomes most uncomfortable.

Many of today’s successful quarterbacks are not succeeding because they are dominating defenses.

They are succeeding because their coaches are.

We see this pattern repeatedly.

Sam Darnold struggles for years in dysfunctional environments. He moves to Minnesota. In a quarterback-friendly system, his efficiency spikes.

Mac Jones fails in New England. He goes to San Francisco. In a structured offense with defined reads, he suddenly looks playable again.

Daniel Jones is inconsistent in New York. He arrives in Indianapolis. In Shane Steichen’s system, with clear structure and timing-based concepts, he plays the best football of his career.

These are not bad quarterbacks, but their success is fragile.

It exists only inside the right system, with the right play-caller, with the right protections, and with the right answers built in.

When the scheme works, they thrive. When the scheme breaks, they do not create.

That is the defining trait of modern quarterbacks.

They are not solving defenses and they are executing instructions.

And that is not a criticism of effort or intelligence. It is the natural outcome of how they were trained. They were taught to trust the system, not override it. They were taught to take the answer, not invent one.

In previous eras, quarterbacks were expected to control the offense. Today, the offense controls the quarterback.

When the first read is open, the system looks brilliant. When it is taken away, the quarterback runs.

That is not evolution. That is dependency.

Philip Rivers and the Proof That Reading Still Wins

The clearest counterexample to all of this came in the most unexpected form.

In 2025, at 44 years old, with a diminished arm and five years away from football, Philip Rivers returned to the NFL and played winning football almost immediately.

He did not do it with arm strength. He did not do it with mobility. He did not do it with scheme.

He did it by reading defenses.

Rivers changed protections constantly. He adjusted plays at the line. He identified pressure. He diagnosed coverage. He threw the ball to the right place at the right time, over and over again.

Physically, he was inferior to almost every quarterback in the league.

Mentally, he was superior to most of them.

He proved something that modern football has tried to forget: processing still matters more than traits.

Rivers grew up in an era where you could not survive without reading defenses. Spread systems did not protect you. RPOs did not save you. You either understood coverage, or you failed.

In a league full of younger, stronger, faster quarterbacks, a 44-year-old with a declining arm was able to nearly win games simply by seeing the field better than they could.

The problem with modern quarterback development is not athleticism. It is not arm talent. It is not creativity.

It is that too many quarterbacks are entering the league without being taught the most important skill the position has ever required: how to read.

Coaches Now Matter More Than Quarterbacks

One of the most revealing shifts in modern football is this: the most valuable asset in quarterback development is no longer the quarterback.

It is the offensive coordinator.

In today’s NFL, quarterback success is increasingly determined by whether a coach can build an offense that hides weaknesses, manufactures answers, and creates easy throws. The best offenses in the league are not built around quarterbacks reading defenses — they are built around coaches preventing quarterbacks from having to.

We see this every season.

Great coordinators design route combinations that isolate defenders. They build in hot answers. They use motion to declare coverage. They simplify progressions. They create space before the ball is even snapped.

When that structure exists, quarterbacks thrive. When it doesn’t, they collapse.

This is why quarterback careers now rise and fall with coaching changes. A young quarterback can look promising one year, regress the next, then be revived in a new system. The player did not change. The environment did.

The modern NFL has quietly flipped the hierarchy of the position.

Quarterbacks used to elevate offenses. Now offenses are required to elevate quarterbacks.

That is not inherently wrong, but it creates a lot of fragility.

Because when the coach leaves, or the scheme stops working, or the league catches up, the quarterback is suddenly exposed. And there is no foundation underneath him.

Peyton Manning essentially ran the offense for most of his career in Indianapolis, so having a quarterback with that level of intelligence in today’s game would be invaluable and incredibly unique. We don’t see guys like him anymore, but at least we got a bit of a glimpse with Philip Rivers.

Why Raw Quarterbacks Without Elite Coaches Are Doomed

This is where the system becomes truly unforgiving.

In theory, the modern model can work. A young quarterback enters a quarterback-friendly offense. He is protected. He gains confidence. He develops gradually within structure.

In practice, it works only if the coach is elite.

A raw quarterback paired with a mediocre play-caller and schemer is almost guaranteed to fail.

If the coordinator cannot design answers versus pressure, the quarterback will panic.

If the coordinator cannot disguise weaknesses, the quarterback will be exposed.

If the coordinator cannot adapt, the quarterback will stagnate.

And because modern quarterbacks are system-dependent, they cannot survive poor coaching.

In previous eras, great quarterbacks could outgrow bad schemes. They could override play calls. They could change protections. They could fix problems at the line.

Most modern quarterbacks cannot.

They have not been trained to.

So when a young quarterback is drafted by the wrong team, with the wrong coach, at the wrong time, his career can be effectively over before it begins. Not because he lacks talent — but because the environment cannot support him.

This is why quarterback bust rates remain so high. It’s not because the prospects are worse, but because the margin for error has disappeared.

The Position Has Been De-Skilled

This is the uncomfortable conclusion that sits at the center of all of this.

Quarterbacks are more athletic than ever. They throw harder than ever. They run better than ever.

And yet, the core intellectual skill of the position has eroded.

Modern quarterbacks are not worse athletes… they are worse readers.

They are entering the league with less experience diagnosing defenses, less experience managing protections, less experience changing plays, and less experience solving complex problems in real time than quarterbacks from previous generations.

The position has been de-skilled by design.

College football simplified offenses to survive roster chaos.

The NFL simplified offenses to survive quarterback underdevelopment.

Coaches became more important than players.

Systems replaced mastery.

And the result is a league full of quarterbacks who can execute plays beautifully — but struggle to command games.

This is why sustained greatness is now so rare.

This is why playoff success is concentrated among a handful of veterans who learned the position before this shift took place.

And this is why the most important trait for the next generation of quarterbacks may no longer be arm strength or athleticism.

It may be whether anyone, anywhere, still knows how to teach them how to think.

My Plea

This is my plea to college football and the NFL, as someone who has trained quarterbacks and watched firsthand how the position is actually built.

Teach them how to think again.

Teach them how to take a snap under center. Teach them three-, five-, and seven-step drops. Teach them how to move in a pocket, not just escape one. Teach them how to scan the full field, not just one defender. Force them to work through three progressions, not one glance and a run.

Stop applauding quarterbacks for clapping their hands and throwing bubble screens.

Teach them how to change protections. Teach them how to identify pressure. Teach them how to walk to the line of scrimmage and decide that the play called is wrong — and change it. Make that part of their job again.

Listen to Jon Gruden when he talks about quarterbacks. Watch old tape of Brady, Manning, Brees, Rodgers, Rivers. Their arms mattered. Their legs mattered. But what separated them was that their minds controlled the game.

They were not passengers in the offense.

They were the offense.

Build offenses that challenge quarterbacks, not protect them from thinking. Allow them to struggle in college so they do not drown in the NFL. Bring back patience. Bring back sitting. Bring back development that takes years, not months.

And do not be afraid to admit when a quarterback is not ready — even if he was the first overall pick.

For Colts fans, Anthony Richardson is the cautionary tale. A rare physical talent thrown into the fire without a real developmental plan, without time, without protection, without a system built to teach him how to survive the position mentally. That is not a failure of talent. That is a failure of process.

If football wants better quarterbacks, it has to start demanding more from them — not less.

Because the next great generation of quarterbacks will not be built by simplifying the game.

They will be built by teaching them how to understand it.