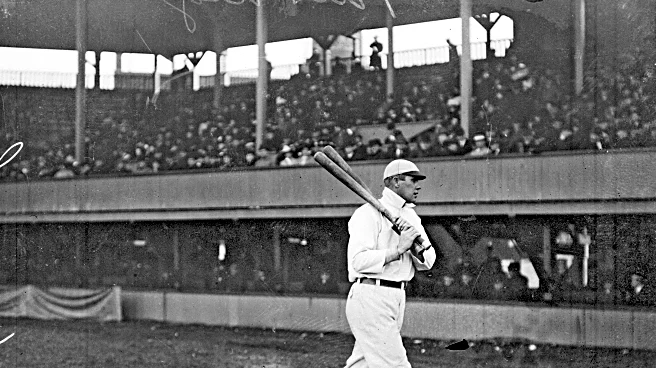

Harry Wolverton is the patron saint of baseball traditionalists. “Fighting Harry” was a third baseman in his 1900s heyday; a journeyman who played with four teams in eight seasons before transitioning

to a managerial career. Wolverton guided the Pacific Coast League’s Oakland club to a surprise second-place finish, which convinced the New York Yankees to hire Wolverton for the club’s the 1912 campaign. Wolverton’s reign did not go great; it was be referred to as “the most Titanic failure of the 1912 season” before the real shipwreck had time to settle on the ocean floor.

So, what did Harry do to earn sainthood? It wasn’t because his father’s full name was literally John the Baptist Wolverton. It’s because, throughout his time with the Yankees, Harry refused to call the club by its name. You see, “Yankees” was a new name. Before Wolverton came over in 1912, the club were known as the Highlanders. Wolverton didn’t care for the name change. Any chance he got, he referred to the club by their old name. Hence, he became a saint for those who cling onto traditions for the sake of tradition.

Harry Wolverton’s spirit dwells within the hearts of those who heard Rob Manfred speak about regional realignment on Sunday Night Baseball and immediately clutched their hearts and reached behind them to feel for their fainting couches. They yelled “tradition” until their faces turned red, teeth gnashed and fists cliched hard enough to mark their palms with the indentation of their fingernails. “Tradition!”

Tradition has been a trusty sword and shield to wield against progress in baseball for centuries. An early example occurred in 1864. People started to complain that the games took too long, so the National Association of Base Ball Players decided to institute a new rule change with pace-of-play in mind. The traditionalists hated the new rule. Umpires refused to enforce it. The new rule struggled to catch on, but it managed to survive the initial onslaught. The players eventually (slowly, begrudgingly) adapted the rule.

What was that controversial rule change? No, it wasn’t a pitch clock. It was balls and strikes.

And just like Harry and the Highlanders, the crusade against called balls seems ridiculous today.

But hey, if your vision of realignment requires the validation of baseball men from the past, I can oblige. Manfred’s regional realignment was first conceived of back in 1985, by a SABR writer named John McCormack. Here is what McCormack had to say about tradition’s opposition to regional realignment:

“The American League was formed in 1901 as a rival to the National League, then in its twenty-sixth year. It soon had franchises in five of the National League’s seven cities. Thereafter it was war, a nasty, bitter war for survival in which anything went. The resulting wounds were deep, the scars long-lasting. Though peace came with the 1903 season, the National League still regarded the upstart with scorn—so much so that in 1904 there was no World Series. The National League’s New York Giants refused to play the American’s Boston Pilgrims, surprise victors of the previous year’s Series. Disingenuously, the Giants proclaimed themselves champions of the only major league: What could they gain through postseason play?

Although peace did not bring good fellowship, it did bring a great asset to the game: league fan loyalty. It was deeply ingrained by the war and was passed thereafter from parent to child. A fan was a National Leaguer or an American Leaguer—if his team didn’t win the pennant, there was always the hope that his league could win the Series. It’s inconceivable, for example, that a true Giant fan would ever have rooted for the New York Yankees in a World Series, even against the loathsome Dodgers.

Continental expansion, which brought the pillage of all but one of the two-league cities (Boston, Philadelphia, St. Louis, and New York—only Chicago remained) just about killed league loyalty. Fans in one-league cities have no feel for the other league. Little attention, let alone passion, is given to it. And, how could it be otherwise? There is no longer animosity between the leagues. Even churlishness is rare. The leagues are, in effect, business partners who put on a display of mock-combativeness at the All Star game and the World Series.

Contrast Connie Mack’s approach to the 1933 All Star game with Whitey Herzog’s to the 1983 game. Mack was there to win. He wanted to humiliate his old antagonist, John McGraw, the National League’s manager. He told his squad that if some did not play, it was unimportant so long as the American League won. Among those who rode Mack’s bench all day were future Hall of Famers Bill Dickey and Jimmie Foxx. His future colleague at Cooperstown, Earl Averill, was luckier. He got to pinch hit. But the American Leaguers won.

In 1983 Herzog’s pregame position toward victory was, “Who cares?” His National League team reflected its leader’s indifference, being battered, 13-3—whereupon Herzog announced to one and all that he was glad the American League had won! John McGraw, Barney Dreyfuss, and Charlie Ebbets must have spun in their graves. Unfortunately for baseball, however, the American League’s victory had little emotional impact on the game’s fans. If the leagues didn’t care who won, why should the fans?”

The two leagues have only grown more homogenized since McCormack’s article. Interleague play is constant. The designated hitter is universal. Nobody identifies as an “American League” fan. Major League Baseball is not an uneasy truce between two rival leagues, and it hasn’t been for decades. If this was truly a hill worth dying on, the transitions of Houston to the AL and Milwaukee to the NL should have been baseball’s Waterloo. Yet somehow, the game has endured.

Even though McCormack proposed regional realignment back when the league only had 26 teams, he imagined a 32-team league for his proposal. Here was his league:

- Northeast: Toronto Blue Jays, Montreal Expos, Boston Red Sox, New York Yankees, New York Mets, Philadelphia Phillies, Baltimore Orioles and (new) a team from Washington, Northern New jersey, or Buffalo.

- Midwest: Pittsburgh Pirates, Cincinnati Reds, Cleveland Indians, Detroit Tigers, Chicago Cubs, Chicago White Sox, Milwaukee Brewers, and Minnesota Twins.

- Southern: Atlanta Braves, Houston Astros, Texas Rangers, Kansas City Royals, St. Louis Cardinals and (new) three teams from among Tampa, New Orleans, Miami, Memphis, and Birmingham.

- Western: San Diego Padres, California Angels, Los Angeles Dodgers, San Francisco Giants, Oakland Athletics, Seattle Mariners and (new) two teams from among Vancouver, Phoenix, Portland, and Denver.

And here is how we could readapt it for 2025, if Portland and Nashville receive expansion teams:

- Northeast: Toronto Blue Jays, Washington Nationals, Boston Red Sox, New York Yankees, New York Mets, Philadelphia Phillies, Baltimore Orioles, Pittsburgh Pirates

- Midwest: Cincinnati Reds, Cleveland Guardians, Detroit Tigers, Chicago Cubs, Chicago White Sox, Milwaukee Brewers, St. Louis Cardinals, Minnesota Twins

- Southern: Atlanta Braves, Houston Astros, Texas Rangers, Kansas City Royals, Tampa Bay Rays, Miami Marlins, Arizona Diamondbacks, Nashville expansion

- Western: San Diego Padres, Los Angeles Angels, Los Angeles Dodgers, San Francisco Giants, Seattle Mariners, Colorado Rockies, the yawning void which features the Athletics, Portland expansion

Much of McCormack’s later arguments don’t hold water for me: He argued that regional pride would result from this realignment, with fans of the White Sox rooting for the Midwest representative in the playoffs. Presumably, this included the Cubs. That is never going to happen. McCormack also wanted to abolish interleague play and re-establish interdivision exclusive scheduling, but I don’t see any good reason to abolish interleague play. I think it’s a fun treat to go down to Sox Park and watch the Dodgers beat our brains in every other year.

But just imagine a Midwest division where the Sox play the Cubs 12 times a year. Both teams were formed in opposing leagues with the goal of driving one another out of business, but now every franchise is on the same team. There is no logical reason to prevent this from happening, other than traditions based in irrelevant circumstances. If you disagree, then I have three words for you: Let’s Go Highlanders.