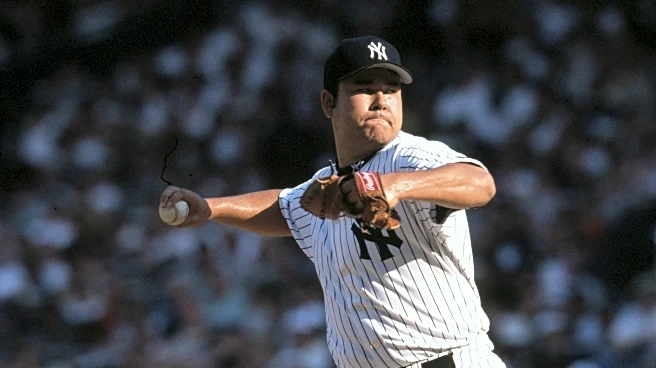

Hideki Irabu occupies a complicated and painful place in Yankees and baseball history. While Irabu was a terrific star pitcher in his home country and was one of the pioneers in the first wave of players

coming from Japan to play in the Major Leagues, his legacy is not one of success and triumph. Irabu never fully settled in as a pitcher with the Yankees, and his struggles earned him the ire of fans, the media, and owner George Steinbrenner. While he became the first Japanese pitcher to win a World Series, he did so without appearing in it.

The Yankees, of course, would continue to win championships with or without Irabu, and in more recent eras would see other players from Japan such as Hideki Matsui, Hiroki Kuroda, and Masahiro Tanaka achieve great success in the Bronx. But Irabu was the first—a man who had said he intended only to pitch for the Yankees and wiggled out of a deal with the Padres in order to do so. (Yes, he His arrival in the Bronx and sensational debut felt like the start of an unforgettable new chapter for the Yankees, already a global brand. Instead Irabu’s momentum petered out, and his life would eventually take a tragic turn.

Hideki Irabu

Signing Date: May 29, 1997

Contract: 4 years, $12.8 million

Irabu was born on May 5, 1969 in Okinawa, which at the time was still administered by the US government. His biological father was an American serviceman named Steve Thompson who left Japan before Hideki was born. Hideki was instead raised by his mother Kazue and his adoptive father Ichiro Irabu in Amagasaki, Japan. He quickly became highly regarded as a pitching prospect in high school, and debuted in pro ball as a 19-year old with the Lotte Orions—later the Chiba Lotte Marines—in 1988. Over the following nine seasons, he became a fearsome ace with a towering presence and searing 98-mph fastball. Standing at 6-foot-4, 240 pounds, he would earn comparisons to Arnold Scwharzenegger for his physique, something which would gain an ironic twinge considering what was to follow.

After bouncing back and forth between the rotation and the bullpen for several years, Irabu hit his stride as a strikeout-heavy starter with the Marines in 1993, with 160 Ks across 142.1 innings. He continued the momentum over the next two years with 239 strikeouts in both 1994 and 1995—seasons in which he threw over 200 innings apiece. That latter year was the first season in the US for fellow Japanese pitcher Hideo Nomo, whose agent Don Nomura had discovered a loophole in Nomo’s contract with the Kintetsu Buffaloes which allowed him to become a free agent and sign with the Dodgers. Nomura was also Irabu’s agent, and in a few years they would be fighting together for Irabu’s opportunity to join the New York Yankees.

The Marines enjoyed total control over Irabu’s rights for a full decade under the terms of NPB’s reserve clause. When MLB teams began showing serious interest ahead of the 1997 season, they made a deal with the San Diego Padres to sell his contract to them. Irabu didn’t want to play for the Padres, so he teamed with Nomura and lawyer Jean Afterman to fight the deal and send him to the Yankees. After several months, they got their wish. In May, the Padres traded Irabu to the Bronx for Rubén Rivera and Rafael Medina. The deal with Irabu was for four years and $12.8 million.*

*One might quibble with Irabu’s inclusion in this accounting of notable Yankees free agents since they did need to make a trade to get him. But remember that he never actually signed a deal with the Padres, so his first MLB contract came with the Yankes; in the end, he certainly got to choose where he pitched like a free agent would.

According to Afterman, who later joined the Yankees front office and remains there to this day, Irabu recognized this as an important fight, not just for himself as an individual player, but for the collective. “He felt very, very aware that if he didn’t make a stand, then other Japanese ballplayers would be forced to go through what he went through. I think he found his cause,” Afterman told Sports Illustrated in 2017. Indeed, this fiasco led to a restructuring in the relationship between MLB and NPB, in the form of the posting system, still in use today.

Irabu’s arrival in New York was met with plenty of fanfare. The newest Yankee memorably received a Tiffany crystal apple from mayor Rudy Giuliani as part of the welcome. Then, of course, he had to do some pitching. Irabu made his MLB debut on July 10 at Yankee Stadium against the Tigers. In his first inning of work, he retired the side in order with a pair of swinging strikeouts. After running into some trouble and allowing an earned run in the third, the Yankee offense picked him up with four runs to give him a cushion. Irabu never looked back, picking up the win on 6.2 innings of work with two runs allowed and nine strikeouts. The next big thing in pinstripes had arrived.

Or so it seemed. Immediately following that euphoric debut, Irabu began to struggle, allowing five or more runs in each of his next three starts to close the month of July. The following two months would be no kinder. He would be sent down to the minor leagues as fan sentiment quickly turned against him. Irabu’s ERA in his debut season, one abbreviated due to all the struggle he had to endure to even get to New York in the first place, was 7.09.

By the start of next season, Irabu had entered an adversarial relationship with the press—both American and Japanese. Unflattering stories detailing Irabu’s personal habits began leaking out in American papers, and the Japanese press contingent was more than happy to pay him back for the perceived slight of leaving NPB for the bigger MLB paychecks.

Despite all that bitterness, Irabu got off to a great start in 1998. While he missed the end of April, he returned on May 1 with a 7.1-inning gem against the Royals to earn his first win of the season. He followed that up with five consecutive quality starts to finish the month—including his first career complete game shutout in a blowout win over the White Sox.

After seven innings of two-run ball in a tough-luck loss in Baltimore, Irabu had a 1.68 ERA through 11 starts. Just as it started to feel as Irabu had finally settled in with the Yankees, batters started to readjust again. He would still have his share of strong starts down the stretch, but they declined in frequency. His worst stretch of the year would come in August and early September, knocking him out of Joe Torre’s postseason plans. The Yankees, of course, would go on to make the World Series against the Padres, the very team that was forced to trade Irabu away. Unfortunately, Irabu was not able to deliver on that tantalizing storyline, but the Yankees swept San Diego to clinch their second Fall Classic title in three seasons.

Irabu’s final numbers in 1998 were by no means bad—a 13-9 record and 4.06 ERA in 173 innings—but given the late-season slide and exacting standards of Steinbrenner, his job was no guarantee entering 1999. That year’s camp produced the epithet which unfortunately would follow Irabu for the rest of his career. In a spring training game, Irabu failed to cover first base with The Boss watching. Steinbrenner, in disgust, called Irabu “a fat pus-sy toad”.

Much of his inconsistency was self-inflicted, because Irabu’s routine often amounted to chaos. He seemed to have a relentless need to stay a step ahead of opponents, so he would frequently change his exercise routines and his pitching mechanics. Compared to many of his Japanese contemporaries who were extremely routine-oriented, Irabu was shifty, nervous, watching his back. The antagonistic billionaire waiting for him to fail so he could push his face in it couldn’t have helped the dynamic.

Naturally, 1999 was another inconsistent year for Irabu. He struggled in May, then surged in June and July, before bottoming out again in the home stretch—a 6.95 ERA in August and 6.20 in September. The Yankees kept humming along in the meantime, and entered another October title defense. This time, Irabu would get his postseason shot, but it came in ignominious fashion.

First, the Yankees were already losing badly. Roger Clemens turned out a dud against the Red Sox in ALCS Game 3, allowing five runs in the first two innings, and got the rest of the night off from Torre. In came Irabu as the mopup man, and he fared no better against a Boston club suddenly clicking on all cylinders. The Sox added four more runs to their total to lead 9-0 after six.

After registering the final out in the sixth, Irabu stormed down the dugout steps into the clubhouse and angrily threw his spikes and belt, before later realizing Torre had never removed him from the game. He hurried back up the tunnel to see his teammates warming up on the field without him. He went out, gave up four more runs in the seventh, and was relieved by Mike Stanton.

That ignominious postseason fiasco marked Irabu’s final game with the Yankees. In December, he was traded to Montreal, and it was honestly fortunate that the Yankees were able to add pitching prospects Ted Lilly and Jake Westbrook in exchange for him. Irabu would appear in just 14 games across two seasons with the Expos, limited by knee and elbow surgery. In 2002, he signed a one-year deal with Texas and operated primarily as a late-inning reliever for the Rangers, registering 16 saves and recording a 5.74 ERA over 47 innings.

After that season, Irabu returned to Japan, pitching for the Hanshin Tigers to decent results in 2003 before only appearing in three games for them the following season. That marked the end of his professional career until 2009, in which he appeared in ten games for the Indy ball Long Beach Armada.

Overall, Irabu’s contributions as a Yankee were not egregious, but forgettable—a 4.80 ERA (95 ERA+) and 4.97 FIP with 315 strikeouts in 395.2 innings. During this period of tumultuous production, Irabu himself was constantly in flux—his translator, George Rose said it seemed that he was “always looking for who he was meant to be”. This made him irritable in the presence of reporters, and made him struggle to enjoy the company of his teammates. And the sense of being different from his peers in Japan never allowed him to feel comfortable back home either.

That tension never really resolved, and as he entered his 40s, he really started struggling with alcoholism. Irabu was arrested in his home country in 2008 for assaulting a bartender Osaka, then stateside in 2010 for driving while intoxicated in California. Those arrests closed his opportunity on working in baseball again, and his continued drinking destroyed his family life as well. His wife and two daughters left him in 2011. That July, L.A. County deputies found him dead in his house in Rancho Palos Verdes. Irabu had taken his own life.

The news shook his former teammates. Catcher Jorge Posada was among those who took the time to remember his former batterymate:

“’It’s really devastating. I got to know him real well … A guy that came out here with a lot riding on his shoulders, but he did a hell of a job for us. Tough times.”

Irabu’s story is deeply tragic; a man who could not feel comfortable in his own skin either in Japan or America. He pursued greatness in baseball, but his restlessness made him unable to remain consistent. He performed a great service in fighting to create the posting system, ensuring that his Japanese brethren would enjoy the right to choose whatever team they wanted to play for in the future. But his three years struggling under the brightest lights in the sport were a profoundly lonely and isolating time for him. He never really the found the comfort and community he was searching for.

See more of the “50 Most Notable Yankees Free Agent Signings in 50 Years” series here.