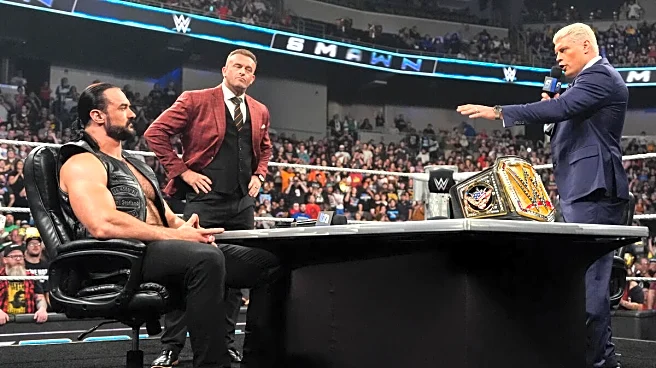

While signing the contract for their WWE title match at Wrestlepalooza a couple weeks back on SmackDown, Drew McIntyre called Cody Rhodes a corporate champion.

Now, depending on who you ask and when you ask them,

that’s either a good thing or a bad thing. On that night in front of that crowd, it was unquestionably a very good thing. Money usually talks, but when it comes to WWE’s business over the last two years, it screams. Their success shows that the Toledo crowd isn’t the only one that approves.

It’s a far cry from almost 30 years ago, when the mere mention of a corporate champion made audiences boo, hiss, and launch anything next to them into the ring like a projectile. The Face That Then Ran The Place built one of wrestling’s most storied rivalries around the idea of never going full boardroom. Stone Cold Steve Austin refused to wear a suit. A necktie was a noose rather than an accenting accessory. He rebelled and found a new cause to do so every week.

Whether he wanted to or not, Austin represented the people. Rhodes does too. There’s no bigger arbiter of change than that fact. Triple H rightly states that WWE reflects the world and adapts with the times.

Then what does it say that Rhodes, an openly admitted kayfabe politician and corporate guy, represents the people? WWE mirrors a world where absolute power reigns absolutely. And, more importantly for the fans, it embodies the notion of welfare for corporations but rugged individualism for everyone else.

Now, this isn’t a knock on Cody the person. Just pointing out that his persona is part of a larger portrait. One that includes higher ticket prices, higher subscription costs, and ultimately a higher barrier to entry. The only thing lower on TKO’s ledger is the number of house shows, which provided an inexpensive way for people without WrestleMania money to partake in the modern traveling circus. Despite viral moments with Randy Orton and WWE CEO Nick Khan, TKO COO Mark Shapiro made it clearer than white crystal that not only are higher prices a permanent fixture in fandom, but that we can look forward to them climbing higher.

Why? Well, besides the obvious answer, Shapiro noted that Vince McMahon “primarily priced tickets for families and wasn’t focused on maxing the opportunity there.”

“There,” in this case, being the revenue generated per ticket. Say what you want about McMahon, and I’ve said plenty, but he apparently had the good sense to keep the dollars and cents somewhat in check because it made sense. Getting families in the door at reasonable prices creates repeat customers who cop a couple of tees, maybe a replica championship, and become fans for life. That process becomes harder in an environment where the prices of everything keep rising faster than yeast. There’s a tragic irony in not having enough bread to buy bread, but it’s a reality that companies are usually keenly aware of. TKO is going the opposite direction and pricing out plenty in the process. No matter how often the wrestlers on screen pander to the audience, the suits in C Suites keep finding more ways to bleed pockets dry in the middle of a drought.

And yet, business is booming. Fans acknowledge the expenses. Wrestlers do too, and nothing changes. A high-ranking CEO with more commas in his bank account than a graduate thesis openly states they can charge more, and nothing changes. That reflects a culture where companies with three-letters on the New York Stock Exchange can move with impunity. Wealth is king without equal, and the masses are its loyal subjects.

When the good guys wear tailored suits, expensive watches, and shoes with hard-to-pronounce names, it conditions the audience to look up to the haves. Lording one’s net worth over the regular folks, explicitly or implicitly, was once heel territory. The Horsemen flexed their lifestyle to piss off the fans. The Rock bragged about his millions of dollars and his $500 Versace shirts to mock people who’ve never even seen a Versace store, much less bought anything in one. The Million Dollar Man was, well, the Million Dollar Man. He believed everybody had a price and often found the perfect figures to humiliate his foes and the innocent.

That inherent conflict only deepened their beef with more relatable fan favorites. Well, relatable-ish. Professional sports entertainment stories, at their most basic, are about the little guy or gal defying the odds against the powerful; it’s populist entertainment at its finest. Yet, despite the increase in undersized bank accounts since the late 1990s, that equation is now inverted for reasons passing understanding. Thus, the thing one could watch on TV, either for free or with basic cable, is no longer populist. It’s now on the other side in our Dickensian saga of haves and have-nots. Not so much let them eat cake so much as let them eat overpriced popcorn.

We’re in a weird moment in history, to say the least. The ‘80s ethos about greed and its goodness seems supercharged. Entertainment is often a refuge during economic or societal strife, but media consolidation means even fun comes with a dose of sticker shock. It’s no wonder WrestleMania tickets cost more than most car notes. And that’s the issue. One shouldn’t have to choose between enjoying a fantastic wrestling weekend in Las Vegas or paying for the car that gets them to the airport. Even watching at home now comes with a $30 per month price tag. We’re a long way from the “$9.99” heyday.

I’m not slighting WWE’s product, which I generally enjoy. Nor is it some tribalism call to raise a competitor’s flag. There’s no knowing what AEW might do if they were in a similar position, despite what they say now when the cameras are on. It’s just that the way TKO, and WWE by extension, handle their business is inescapable. And I recognize the hypocrisy in complaining without taking action. I could quit Peacock, ESPN, Netflix, and this gig that I love tomorrow. That would draw a line in the sand against their habitual line-stepping. I shouldn’t have to, though. None of us should have to do any of those things in 2025, where joy is at a premium.

It’s incredible, even in kayfabe, that the grandson of a plumber sits atop the WWE mountaintop as “QB1.” But it’s telling when that character sits in opposition to the one thing the son of a plumber once represented proudly, loudly, and unapologetically: the common man.

A form of entertainment that once stood with that common man now feels like it stands against him. Not because it has to, but simply because it can.

It’s all about the money, and that’s the bottom line.