There are generally enough players, managers, coaches, et cetera, for us to be able to do this Yankees birthday series without issue. Sure, 365 days is many, but so far, we’ve been able to get at least

one Yankee of interest to look back on for every day.

Unfortunately, today we couldn’t. Somehow, January 14th is not the birthday of a single player from Yankees history. However instead, this gives us the opportunity to look back on someone else from New York baseball history — someone who we probably wouldn’t ever talk about in other circumstances, and someone who could’ve been a good Yankee had the baseball world not been as racist as it was at the time.

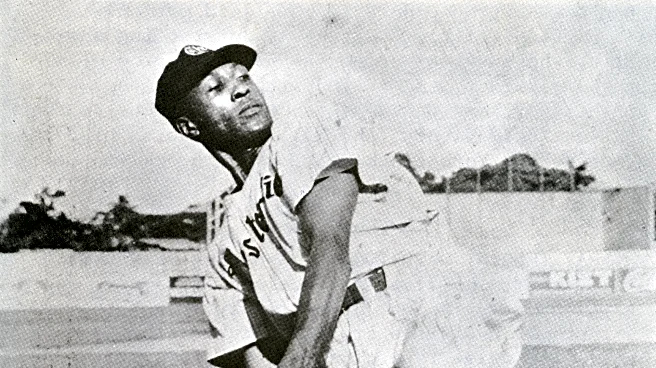

Chester Arthur Brewer

Born: January 14, 1907 (Leavenworth, KS)

Died: March 26, 1990 (Whittier, CA)

New York Cubans tenure: 1936

Born in Kansas in 1907, Chet Brewer and his family moved to Iowa when he was a child. Unlike the state of his birth, Brewer could attend an integrated school in Iowa. He took up baseball at a young age, becoming a pitcher. He eventually caught the eye of probably the most famous of all the Negro Leagues teams, the Kansas City Monarchs, who signed him in 1924, when he was just 17 years old.

Brewer made his debut the following season, but struggled in a handful of innings. However, he quickly figured things out the following season. At just 19 years old in 1926, Brewer went 12-1 with a 2.37 ERA (a 192 ERA+, for reference), helping the Monarchs win the Negro National League pennant.

While he fell back to earth in the next two seasons, Brewer then bounced back with a career year in 1929. With a 15-2 record, a 1.93 ERA (222 ERA+), 14 complete games out of 15 starts, and a league-leading 6.1 rWAR. As a team, also managed by Brewer’s childhood hero Charles “Bullet” Rogan, Kansas City went a remarkable 63-17 and won the NNL pennant again.

Employment in the Negro Leagues wasn’t always as steady, with leagues and teams often changing. A lot of players back then used to not always play in the organized leagues, often joining semipro or barnstorming teams. Brewer did plenty of that himself, as he only played one season of organized ball from 1931-35. In one particular game during that time, Brewer reportedly shut out a team featuring some white stars of the time, including Hall of Fame Yankees catcher Bill Dickey and legendary Philadelphia A’s slugger Jimmie Foxx.

In 1936, Brewer returned to the Negro National League and joined the New York Cubans, which is the reason we’re highlighting him today. The Cubans played some games at Yankee Stadium, but their primary home in ‘36 was Hinchliffe Stadium in Paterson, NJ, which still stands today (following recent renovation). Brewer’s one season with the Cubans wasn’t as dominant as some of the ones he had put up with the Monarchs, but he did record a league-leading nine complete games. The following year, he would join the legendary Satchel Paige alongside a number of Negro League stars who played down in the Dominican Republic, as dictator Rafael Trujillo was paying players big money in an attempt to strengthen baseball in the country.

Brewer journeyed all around the Americans over the rest of his career, as well as serving in the military during World War II. As the color barrier began to thaw, Brewer was almost given several opportunities, only for them to evaporate. Two separate offers to play for Pacific Coast League teams ended up being rescinded. A farm team in the Cleveland system was going to hire Brewer as a player-manager, only for GM and former Yankee Roger Peckinpaugh to nix it.

Brewer continued pitching all the way through 1952, and even became one of the first black minor-league managers that season with the Porterville Comets in California. After retiring from playing, he became a scout for the Pirates, receiving a World Series ring when the team won the championship in 1971. He also went on to establish a baseball program in inner city Los Angeles, which produced a couple major leaguers, including future Yankees first baseman and GM Bob Watson.

Chet Brewer was a Negro League All-Star and led the leagues he played in different stats on a different occasions, in an era where the likes of Satchel Paige was still playing. In fact, Paige listed Brewer as a player he believed worthy of induction to the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. (That honor has not yet been given.) Sure, it would’ve been nice to know just how good he could’ve been in MLB play, but he still lived a very rich baseball life.

Reflecting on his work with kids, Brewer said:

“I don’t believe in hate. I do believe in righting wrongs. Hate puts both of you in the grave. Working with kids at clinics, I do more good in five minutes than the hate groups will do in five years.”

See more of the “Yankees Birthday of the Day” series here.