What's Happening?

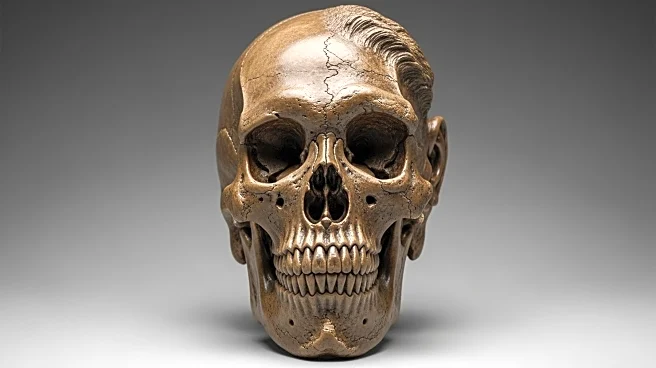

A re-analysis of the Skhul child skeleton, found in Israel's Skhul Cave, suggests prolonged interbreeding between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals. The remains, dated to around 140,000 years ago, exhibit a blend of traits from both species, challenging previous timelines of Neanderthal and human interaction. The study, conducted by an international team including Tel Aviv University and the French National Centre for Scientific Research, used advanced imaging techniques to reveal Neanderthal-like features in the jaw and inner ear. This discovery indicates early population contact in the Levant, a region known for complex social behaviors and intentional burials.

Why It's Important?

The findings from the Skhul child fossil provide crucial insights into the genetic history of humans and Neanderthals, suggesting that interbreeding occurred over a longer period than previously recognized. This challenges existing theories about the timeline and nature of human migration and interaction with Neanderthals. The study highlights the Levant as a significant meeting zone for ancient populations, offering a deeper understanding of the cultural and genetic exchanges that shaped human evolution. It also emphasizes the need for integrating genetic data with fossil analysis to accurately trace human ancestry.

What's Next?

Future research may focus on extracting ancient DNA from the Skhul remains to confirm hybrid ancestry and further explore the genetic relationship between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens. Researchers may also apply similar imaging techniques to other fossils in the region to identify Neanderthal traits and better understand the dynamics of ancient population interactions. Additionally, the cultural record of the Levant may be re-evaluated to assess the implications of these findings on early human social behaviors.