By Erin Banco, Sarah Kinosian and Matt Spetalnick

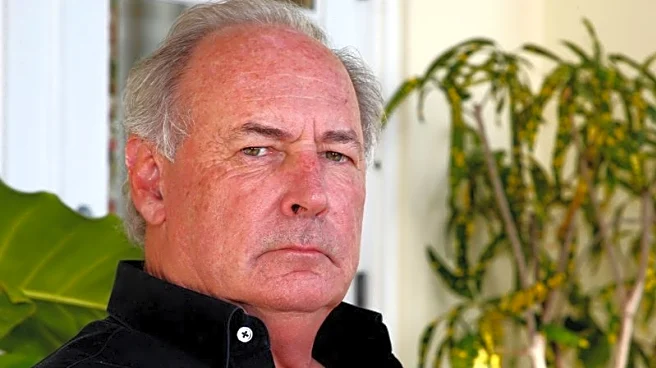

WASHINGTON, Jan 8 (Reuters) - Billionaire energy entrepreneur and Republican donor Harry Sargeant III and his team are advising the Trump administration

on how the U.S. can engineer a return of some American oil companies to Venezuela, according to four sources familiar with the matter.

The involvement of Sargeant, who has long-standing ties to Venezuela’s oil industry, underscores the Trump administration's reliance on U.S. oil executives for guidance on how to administer the country's energy sector following last week's dramatic U.S. military operation that resulted in the arrest of President Nicolas Maduro.

Secretary of State Marco Rubio said on Wednesday the U.S. would refine and sell up to 50 million barrels of Venezuelan crude, as U.S. forces continued seizing oil tankers linked to Venezuela.

"That money will then be handled in such a way that we will control how it is disbursed in a way that benefits the Venezuelan people," he said.

Sargeant's business interests in Venezuela are relatively small in comparison to the oil giant Chevron, the only U.S. oil company with federal authorization to export oil from the country, but he has been doing business there since the 1980s.

Sargeant's businesses buy and export asphalt, which can be made from the kind of heavy crude oil produced in Venezuela, and he has invested in the production of several of the country’s oil fields.

He also has a long history of dealing with senior Venezuelan officials, including Maduro and interim President Delcy Rodriguez, he told Reuters.

Sargeant has long-standing connections to U.S. President Donald Trump and often golfs with him at Mar-a-Lago, two sources said.

Sargeant has met with senior Trump officials in recent days, including Department of Energy Secretary Chris Wright in Miami, one of the sources familiar with the matter said. He has discussed with officials the need for investment in upgrading Venezuela’s oil infrastructure and advised on what terms the Venezuelan government may be willing to offer in contracts, the sources said.

In an interview, Sargeant confirmed that members of his team, including his son Harry IV and executive Ali Rahman, have been in discussions with U.S. officials but said he is not formally advising the administration.

Like other oil executives, he said he encouraged the administration to deal with Rodriguez over opposition leader Maria Machado. "I think Delcy will, when the time is right, be willing to transition the country to democracy and, you know, and see free and fair elections," he said.

The White House did not comment on Sargeant or his role, but a senior administration official said that Trump is "exerting maximum leverage with the remaining elements in Venezuela and ensuring they cooperate with the United States by halting illegal migration, stopping drug flows, revitalizing oil infrastructure, and doing what is right for the Venezuelan people.”

The U.S. Department of Energy did not respond to a request for comment about Sargeant. A spokesperson for the Venezuelan government and Delcy Rodriguez did not respond to a request for comment.

OIL MAN WORKING IN TURBULENT COUNTRIES

Sargeant is the former finance chairman of the Florida Republican Party. His family and corporate entities have donated millions of dollars to Republicans in recent years, according to campaign finance records. Between 2019 and 2020, Sargeant’s wife Deborah donated $285,000 to the Trump Victory Fund, the records show.

Sargeant has worked in the oil sector in some of the most politically turbulent countries across the world. During the Iraq war, Sargeant contracted with the Pentagon to transport fuel to U.S. troops.

In 2009, he was accused by the Congressional Oversight Committee of having overcharged the Pentagon for oil contracts during the Iraq War.

Sargeant denied the allegations and in 2018 a Defense Department investigation found “no fraud vulnerabilities” and stipulated his company would receive a $40 million payment for its government contract work in Iraq.

One of his companies, GlobalOil Terminals, exported asphalt from Venezuela until last spring when the U.S. Treasury Department revoked its license.

The move was part of a pressure campaign against Maduro by U.S. President Donald Trump, whose first administration imposed sanctions on Venezuelan oil.

The energy magnate is one of several major oil executives helping senior administration officials plan a long list of projects to revive Venezuela's oil and gas industry after decades of mismanagement, underinvestment and sanctions. That includes increasing oil supplies to the U.S. and other markets and foreign investment for infrastructure, two of the sources said.

“There are very few people inside the U.S. government who have the industry expertise to be able to run this thing,” one of the sources said, referring to Venezuela’s oil sector. This person, like others in this story, requested anonymity to discuss internal administration deliberations.

While several energy executives have been in touch with the administration in recent days, Sargeant is one of the most influential in part because of his relationship with Trump.

Sargeant told Reuters that he “has never talked to the president about Venezuelan oil.” Reuters could not independently confirm this account.

RELATIONS WITH MADURO, RODRIGUEZ

Sargeant’s companies have for years worked with the Maduro government and the state-run oil company PDVSA.

A company partially owned by Sargeant sought out a deal with the government in 2017 to rehabilitate three oil fields, as Reuters exclusively reported at the time. And in 2024, following the easing of some U.S. sanctions, it struck a deal with PDVSA for the equivalent of 570,000 barrels of asphalt to be used for projects in the U.S.

The Republican donor has also previously been involved in the Trump administration’s outreach to Venezuelan leadership.

In February 2025, he helped broker a meeting between special U.S. envoy Richard Grenell and Maduro in which the two discussed the deportation of migrants back to Venezuela, the release of American prisoners and the potential extension by the U.S. of a license for Chevron to operate in the country, Sargeant told Reuters.

The U.S. eventually announced Chevron’s license would be extended. Chevron did not immediately respond to a request for comment about their licenses or Sargeant's role.

Sargeant and other oil executives close to the administration have advised the U.S. government that Rodriguez would likely be a better choice for interim president because she could better control the oil sector and ensure American oil companies’ access than opposition leader Maria Machado, according to two of the sources.

In conversations with Rodriguez, U.S. officials, including Secretary of State Marco Rubio, have discussed how American companies, fearing legal and financial risk of investing in Venezuela, would need favorable contracts in order to return to the country, two of the sources said.

Reuters could not establish whether Rodriguez has committed to the request or exactly what terms she would be willing to offer American oil companies. But one person familiar with the discussions said the administration is confident Rodriguez will deliver.

Sargeant said that members of his team in Venezuela have been in touch with Rodriguez since Maduro had been captured, but that he himself had only had a text exchange to wish her success in her new role.

(Reporting by Erin Banco in New York, Sarah Kinosian in Mexico City, and Matt Spetalnick in Washington. Additional reporting by Marianna Parraga in Houston. Editing by Don Durfee and Michael Learmonth)