By Marcela Ayres

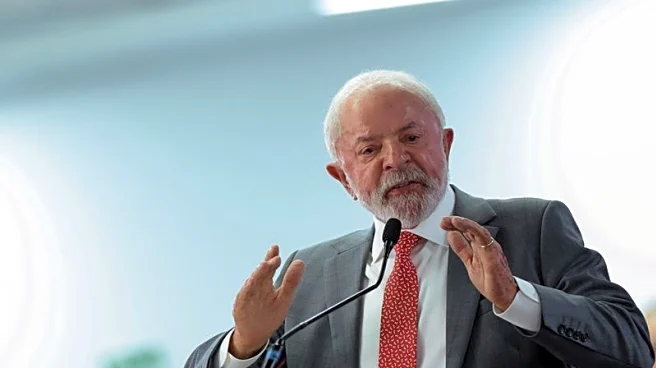

BRASILIA, Feb 11 (Reuters) - A middle-class tax break that nearly halves the number of Brazilians paying income taxes is adding to economic tailwinds that give President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva an edge in early opinion polls as he gears up to run for reelection.

The measure, one of his hallmark promises from the 2022 campaign, reflects an effort to widen the leftist leader's appeal beyond his traditional lower-income base.

It is likely to add steam to an economy that is, though not

booming, at least helping Brazilians stretch their paychecks further. Unemployment is at a record low, the median wage is at a record high and inflation - especially for food - has cooled enough that interest rates are set to start falling next month.

That has helped shore up support for Lula, who leads likely challengers by four to seven percentage points in recent polls simulating head-to-head scenarios for October's election.

Adding to that brightening backdrop is the new income tax exemption for monthly salaries up to 5,000 reais ($960) - over three times Brazil's minimum wage - starting with January payroll deductions.

PILATES, TRAVEL PLANS

Advertising professional Vitoria Santos, 30, plans to spend the extra 300 reais that just landed on her monthly paycheck on Pilates exercise classes.

"It's a meaningful amount that really makes a difference," Santos said. "For some people, it covers the electricity bill for the month, the internet bill, helps pay for travel plans or a gym membership."

Because the extra disposable income will flow mainly to lower-income households that tend to spend extra money rather than save, according to statistics, the government expects the measure to inject around 28 billion reais ($5.4 billion) into the economy this year.

However, many economists are skeptical of the policy's long-term benefits, arguing Brazil should expand its tax base to deal with soaring public debt.

"It's bad economic policy, but it wins votes," said Fabio Kanczuk, a former central bank director and now head of macroeconomics at Asa Investments.

He questioned the wisdom of a tax break for Brazil's middle class, which diverts resources into consumer spending that could have boosted economic productivity or more effectively reduced inequality.

Kanczuk said the stimulus is likely to quickly turn into consumption, including via credit expansion, as banks anticipate stronger household income. He estimated a boost of 0.2 percentage points to economic growth this year, with a similar effect on inflation.

SHRINKING TAX BASE

Roughly 11.3 million of the 25.4 million Brazilians who paid income tax last year, about 44%, are estimated to have dropped off the rolls, the tax authority told Reuters. Another 5.7 million received tax reductions, as the discounts were extended to incomes up to 7,350 reais.

The shrinking income tax base underscores how heavily Latin America's largest economy relies on taxing consumption over goods and services.

It also reflects the priority Lula is giving to more affluent Brazilians after pouring public spending in recent years into programs that largely helped the poor, including cash transfers, assistance for the low-income elderly and disabled, cooking gas subsidies and financial aid for high schoolers. In recent years, the more affluent middle class has shifted strongly toward Lula's opponents on the political right.

Over the past year, Finance Ministry sources said the government has calibrated policy to reach middle-income households, such as subsidized mortgages for families earning up to 12,000 reais a month and buying homes valued at up to 500,000 reais.

Senator Flavio Bolsonaro, the son of Lula’s predecessor, who is seen as his main opponent, has signaled an economic agenda favoring tax cuts and a smaller role for the state.

SPENDING BOOST

Previously, Brazil granted an income tax exemption on monthly wages up to 3,036 reais, or two times the minimum wage.

The reform taking effect this year has broadened relief. The full exemption now applies to workers earning slightly above three times the minimum wage. Brazilians making up to 4.5 times the minimum wage have collected partial discounts.

That upper threshold includes workers such as Emerson Marinho, a 51-year-old postal worker, whose deduction from his latest paycheck fell by 110 reais.

"It's extra money I can put toward food," Marinho said. "I have two children and that represents two full weeks covering fruit and vegetables at home. It really does matter."

To offset lost revenue, the government introduced a minimum income tax on monthly earnings above 50,000 reais, and a 10% withholding tax on corporate dividends sent abroad.

The shifting tax burden is expected to reduce income inequality in Brazil by 1.1%, according to a study by the Budget and Financial Oversight Consultancy in the lower house of Brazil's Congress.

Bruno Funchal, CEO of Bradesco Asset Management and a former Treasury secretary, warned that policies boosting consumption and public spending were part of an "unsustainable" growth model that has pushed interest rates to a nearly 20-year high.

He argued Brazil should instead be cutting its debt and encouraging long-term investments, but recognized such an abrupt policy shift was unlikely ahead of the October vote.

"In elections, there is generally a tendency to avoid prescribing bitter medicine that will eventually be necessary," he said.

($1 = 5.21 reais)

(Reporting by Marcela AyresEditing by Brad Haynes and Rod Nickel)