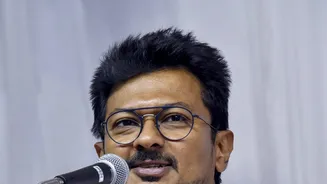

Shivamogga, Karnataka: Karnataka Energy Minister K.J. George has underscored the importance of the upcoming Sharavathi Pumped Storage Project (PSP) in tackling India’s growing renewable energy challenges,

calling it “a practical solution to ensure clean power when people need it most.” Speaking about the project, he said, “It’s easy to oppose projects in theory, but when the lights go off, it’s projects like this that keep our hospitals, schools, and homes running on clean energy instead of coal.”

Energy Storage

Officials from the Karnataka Power Corporation Limited (KPCL) echoed the minister’s view, noting that energy storage is now “the missing link” in India’s green transition. “Storage is no longer optional,” said a senior KPCL energy planner. “We’re producing enough renewable energy, but unless we can store and dispatch it, we’ll stay locked in the coal cycle.”

Renewable Energy Resources

In Shivamogga district, the Sharavathi PSP is quietly taking shape — a project that could redefine how India balances its renewable ambitions with its energy security needs. The idea is simple: if India wants to run on the power of the sun and wind, it must first master how to store that power efficiently.

India's Leading Renewable Push

Karnataka today leads India’s renewable push, generating over 16 gigawatts (GW) of solar and wind power — nearly three times more than in 2016. But that success has exposed a paradox: solar generation peaks at noon when demand is low, while power usage surges after sunset. The mismatch forces utilities to turn back to coal plants, undermining part of the environmental progress made.

Sharavathi Pumped Storage Project

The Sharavathi Pumped Storage Project aims to close this gap by acting as a giant natural battery. It will use surplus solar energy to pump water from a lower to an upper reservoir during the day. When demand spikes at night, that water will be released to generate power through turbines — delivering renewable electricity on demand.

Crucially, Sharavathi’s design avoids the large-scale environmental disruptions typical of older hydro projects. It leverages the existing Sharavathi–Linganamakki reservoir system, requiring minimal new land for tunnels and underground facilities. Officials confirm that only eight families are affected, all of whom will be fully rehabilitated.

Infrastructure

For policymakers, the project represents not just infrastructure, but a strategic pivot in India’s renewable future. With national renewable generation projected to touch 500 GW by 2030, energy storage will determine how much of that capacity can be reliably used. Pumped storage, experts say, offers a proven, cost-effective, and sustainable answer.

If Karnataka can complete Sharavathi on schedule, it could provide the blueprint for round-the-clock renewable energy across India — clean, continuous, and climate-resilient.