The lights were still off outside when I reached the Museum of Flight's Restoration Center and Reserve Collection in Everett, Washington, an hour outside Seattle. The heavy overcast matched the gloom of the essentially

abandoned aircraft just behind the restoration center on the flight line. Austin Ballard, the restoration center's supervisor, told me how few visitors the museum has had since it closed its doors to the public early in the pandemic; in fact, it has yet to reopen them. But with a warm smile, he let me in and showed me around the museum's island of misfit planes.

It didn't take long to find what I was looking for. Crammed into the hangar, surrounded by aviation relics spanning numerous eras, was the better half of a plane. It certainly wasn't airworthy — in fact, it was never meant to fly. Despite this, however, this timeworn artifact once represented hopes of a supersonic future for both Boeing and America.

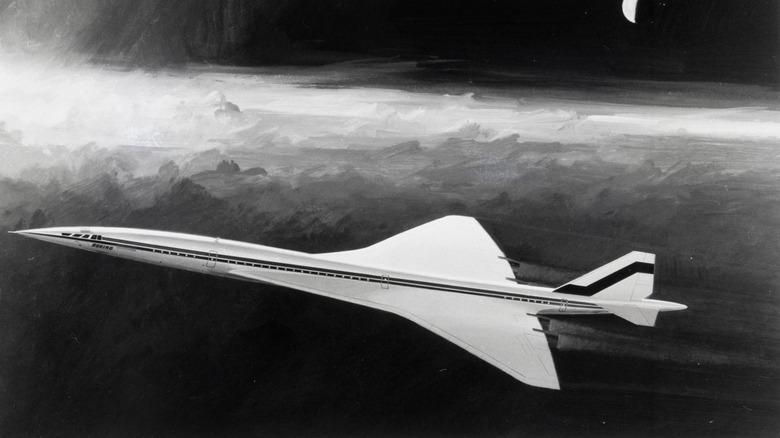

As the winner of the Supersonic Transport (SST) project, the Boeing 2707 promised to outrun and outcarry the British-French Concorde (you can watch workers build the last Concorde here), and bring faster-than-sound travel to the everyday American. But it wasn't to be. With sonic booms proving too loud for land routes, combined with an ongoing litany of developmental setbacks, the SST program was canned, and all that was left was the jet's full-sized mockup.

Today, 54 years later, only the plane's front half remains. But after serving several decades as a museum piece, evangelical church decoration, and roadside attraction, the fact that anything of the SST remains is nothing short of a miracle. And in fact, although the mockup returned to near its birthplace a decade ago, its future remains in jeopardy.

Read more: These Are The Best Engines Of All Time, According To You

From Mach 3 To Mockup

The first domino was knocked in 1962, when a partnership between France and the U.K. was announced to build a supersonic commercial aircraft — one that could challenge America's global dominance of the aviation industry. The Concorde was set in motion, and President John F. Kennedy responded with the SST program, in which federal funding would go to any company that could build a plane able to surpass the European opposition's capacity and speed.

With an all-titanium body and fighter-like swing wings, Boeing's 2707 mockup promised to carry 250 to 300 passengers at speeds nearing Mach 3. The company won the contest, but ran into immediate issues during its development. Specifically, the plane's proposed swing-wing design proved to be too heavy and, like many of its proposed features, too sophisticated for late '60s technology.

The project had also begun losing public support. In 1964, a planned six-month test for sonic booms in Oklahoma City had to be cut short after 15,000 residents listed noise complaints, and nearly 150 windows shattered in two of the city's tallest buildings. Other environmental concerns entered the fray, too, with fears of the plane's impact on the ozone layer. Ultimately, the rising scrutiny from the public would be the final nail in the project's coffin. The SST program was canceled in 1971, and all that remained of the project was the full-sized mockup.

From Seattle To Sermons

Boeing sold the mockup in a sealed auction the following year. Nebraska-based millionaire Mark Morrison bought it for $31,119, with ambitions to use it as the centerpiece of a new aviation museum. In January of 1973, the plane was disassembled and loaded onto seven railroad cars, journeying from Seattle to the new SST Air Museum in Kissimmee, Florida, not far from Walt Disney World.

The museum opened later that year, but failed to draw enough attendance and closed in 1981. Several years and a handful of lawsuits later, the land was sold to the Faith World church, which used the former museum site until 1988. It was bought by a second church, the New Life Assembly of God, the following year. With the plane being too big and expensive to move without demolishing the museum building, the SST somehow stayed. For about a year, the mockup served as the backdrop of services until expansion plans finally forced the plane out.

The wayfaring mockup was nearly sold to be scrapped, but was saved by a former NASA employee turned collector, Charles Bell. The mockup was disassembled and transported to Merritt Island, where it became a roadside attraction of sorts, with tourists stopping to take pictures of the chopped-up plane. This wasn't the only relic of supersonic travel abandoned in the Sunshine State, but for nearly a decade, the ill-fated aircraft was left to rot in the Florida sun.

Salvation In San Carlos

Salvation came for the SST around May of 1998, when Stan Hiller purchased the remains from Bell for $50,000. One of the pioneering developers of the helicopter, Hiller was setting things in motion for his own aviation museum in San Carlos, California, set to open in June of that year. However, space was limited at the plane's new home, and after eight relentless years exposed to Florida's blistering sun and salty air, much of the aircraft was beyond the point of restoration.

"It was in pretty deteriorated shape once we got it," Willie Turner said in a phone interview with Jalopnik. Turner, Hiller Museum's vice president of operations, is one of those who worked for the museum when the SST was around. "We were offered, I guess, the entire aircraft, and we didn't have any place to put it, so we just took the nose section."

Turner told Jalopnik that Hiller upgraded the mockup, with additions including a full-fidelity cockpit donated by Boeing and a functioning droop snoot system installed by the museum. Made to help pilot visibility during takeoff and landing, the nose of the aircraft could be manually raised and lowered.

After the mockup had been treated to a comparatively peaceful 15 years in California, the Hiller Museum decided to let it go as part of a major revamp. A deal was struck with the Museum of Flight in Seattle, and in April of 2013, the plane was traded, loaded onto a truck, and transported back home for the first time in over 40 years.

A Melancholy Reunion In Seattle

Now at the Museum of Flight's restoration center at Paine Field, the fuselage has shared a home with the complex that once could have served as its production line. Here, the relic has sat gathering dust for the past 12 years. Little work has been done on it since it returned home. Its cockpit has been removed, and its droop snoot separated from the remainder of the aircraft to save space. The SST has seen better days, but over the past 50 years, I can guarantee it's also had far worse.

Being put on display would be a full-circle moment for the SST, but Austin Ballard has his doubts. "I'd love to see it, but I'm not so sure if it will ever make it into Seattle," he said. "You gotta remember that this plane really is a black eye for Boeing."

He's right. The cancellation of the SST on March 24, 1971, led to 7,000 workers being laid off immediately, as well as an additional 60,000 Boeing employees being let go over the following two years. What was ultimately dubbed the "Boeing Bust" brought about devastating shockwaves that rippled through Seattle and Washington's economy, causing unemployment to skyrocket all over the Evergreen State. Had it not been for the 747 (now, decades later, reaching the end of the line) and the 707, the SST could have been the project that put Boeing in the grave. Although the 2707 would certainly serve as a one-of-a-kind exhibition piece, putting it on display in Seattle would be a reminder of a high-profile missed opportunity for the city, Boeing, and American aviation.

A Sign For The Future?

While the SST program will remain an unpleasant memory for Boeing and the Puget Sound area, its legacy still deserves to be celebrated. Riding the coattails of incredible advancement, the SST is a relic of an era that exuded endless optimism for the future. By the late 1960s, humans had gone from propeller-driven airliners to swift, silent jetliners. And in a decade where the world was introduced to such marvels as satellites and moon landings, it's no surprise that the sky — and beyond — felt like the limit.

But the 2707 doesn't just stand as a monument to what has been, but also as a vision of what absolutely could still be. Boom Supersonic's "boomless" XB-1 prototype successfully flew supersonic earlier this year without a single sound being heard on the ground. And with NASA promising quiet booms in the near future via its X-59 project, supersonic flight may be back on the menu for everyday air travel. None of those lessons could have been learned had it not been for the example set by the SST.

To say the SST was controversial is a vast understatement, but with countless lessons learned in its wake, it laid the groundwork for supersonic airliners in the 21st century. Aside from what the concept stood for, the mockup may be the only plane to go from the Atlantic to the Pacific without ever leaving the ground. Cheating death and having a more colorful resume than many other grounded aircraft, the Boeing 2707 deserves its time in the spotlight once more ... as the plane it was supposed to be, and the resounding precedent it set.

Want more like this? Join the Jalopnik newsletter to get the latest auto news sent straight to your inbox...

Read the original article on Jalopnik.