Bollywood has long been one of the world’s most prolific storytellers, with the romances, dramas and musicals it churns out having shaped cultural perceptions of love, gender, desire and power. But have you ever wondered why is it that the man in cinema is often allowed far more leeway when it comes to romance? Sometimes the hero is outright creepy or even exhibits stalker syndrome when it comes to pursuing the object of his affection (Think R Madhavan in RHTDM or even Shah Rukh Khan in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai) – and it is all okay! Vicky Kaushal and Richa Chadha had even collaborated with the comedy collective All India Bakchod (AIB) for a spoof video (read cultural criticism) on this. As the world evolves within the context of #MeToo and feminist

critique, one wonders - has the male gaze in Bollywood truly evolved as well, or is love still fundamentally celebrating the man? Perhaps, we have to first understand what is meant by the male gaze and understand that love is not built around male pursuit.

What Is the Male Gaze?

Coined by film theorist Laura Mulvey as late as 1975, the male gaze refers to the way visual arts are structured around a masculine viewer. In cinema, this basically translates into women being presented as objects of male desire – defined by how they look rather than who they are (yes, mostly every nineties commercial Bollywood flicks ever). Their bodies and emotions are framed through the desires and perspectives of men. However, over time, social changes and new voices started challenged this framing. But the question remains,

has Bollywood fundamentally shifted its gaze when it comes to love stories?

Bollywood, Traditional Paradigm and Love through the Male Lens

Classic Bollywood romances have often centered male desire and heroism. The 1995

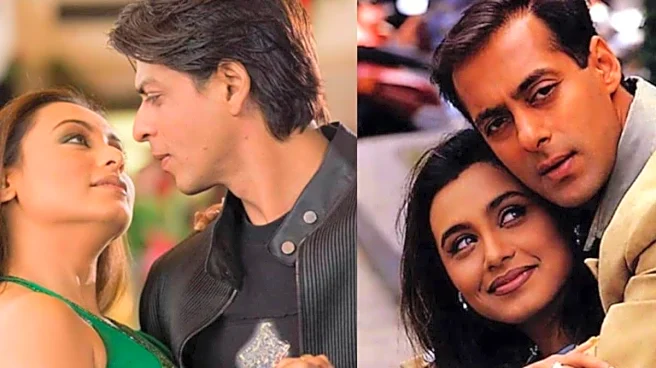

Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge, starring Shah Rukh Khan and Kajol in lead roles – a film that is definitive of the era, framed love through the male hero’s pursuit. While Simran is charming and spirited, the narrative is driven by Raj’s pursuit and concludes only when the man ‘wins’ the woman – that too after being approved by the heroine’s father. Similarly the 1998 Karan Johar drama

Kuch Kuch Hota Hai too sees a male gaze not just in visuals but in emotional priority. Kajol’s Anjali pines for Shah Rukh Khan’s Rahul, but the narrative arc centres on his emotional journey. The film treats her transformation into a more conventionally attractive woman as the key to deserving love. And there is something definitely unsettling about the way a dead Tina (Rani Mukerji) urges their daughter to champion her father’s feelings for his once-best friend over the child’s emotional sanity.

The 2001

Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham… though a family saga, revolves around male characters asserting authority, making choices, and defining the emotional terms of relationships –

women be damned. What is unfortunate is that in these stories, even when women are strong and have the capability of agency, the narrative power rests with the man – their desires, their decisions and often their redemption arcs.

Bollywood’s Slow Shift towards Women with Agency

However, the last decade or so has seen several films that have emerged as challenges to the traditional male gaze by offering women greater emotional agency and narratives shaped by their experience of love. Foremost among these, quite possibly is the 2013

Queen. Rani (Kangana Ranaut), jilted before her wedding, embarks on a solo honeymoon, instead of succumbing to heartbreak. The film is revolutionary not for rejecting love entirely but for showing a woman discovering herself that is not defined by a man’s presence. Similarly Deepika Padukone’s 2015

Piku, while not a conventional romance, sees her navigate personal and emotional landscape, even as her romantic life is not a climactic destination.

The 2016

Lipstick Under My Burkha is perhaps the most explicit challenge to the male gaze, in the way it paints four women seeking sexual and emotional gratification beyond patriarchal expectations. In fact, the 2025 Anurag Basu anthology film

Metro… In Dino challenges the male gaze by shifting love from male pursuit to mutual vulnerability, giving women interiority, dissatisfaction, and the power to choose. These films show Bollywood can and sometimes, does make space for stories where women are not framed solely as objects of desire or prizes to be won. They in turn show love depicted with nuance – a bildungsroman of self-discovery entwined in conflict, and complexity.

Basu’s Metro… In Dino enters a romantic landscape when the grammar of love itself is evolving. Unlike older Hindi films where romance revolved around male conquest, the ensemble urban drama complicates who gets to desire, who gets to decide, and who controls closure.

But is Love Still Celebrating the Man?

Let’s be honest, even as women’s stories gain ground, there remain recurring tropes in mainstream love stories that subtly re-centre the male experience. In films like

Kal Ho Naa Ho (2003) Aman sacrifices his love for Naina’s happiness - a noble gesture, but the emotional focus is his sacrifice. Similarly in the 2016 Ranbir Kapoor starrer

Ae Dil Hai Mushkil, The story of unrequited love places the male protagonist’s emotional suffering at the centre. A woman’s love is still treated as a reward for the male protagonist’s journey

Add to that the woes of visual storytelling. Despite championing narrative changes, many songs and visuals still frame women as objects of desire, lingering on their bodies for the male gaze. Dance numbers like

Chikni Chameli from the 2012

Agneepath, or

Balam Pichkari from the 2013

Yeh Jawaani Hai Deewani, may be fun but are rooted in visual consumption rather than emotional agency.The biggest problem however, is perhaps the expectation that women should be available emotionally, along with being empathetic and supportive. Narratives often spend way more time exploring a man’s struggle to express love than a woman’s internalisation of feelings.

Contemporary Examples, Mixed Signals in Darlings, Shiddat, Jab We Met

Recent times have seen films sending out mixed signals in what they are trying to portray. The 2022

Darlings – a dark comedy starring Alia Bhatt tackles domestic abuse and female agency. It is a rare Bollywood film that approaches love and relationships from a woman-centered perspective.

Shiddat (2021) on the other hand, still depicts love through obsessive male pursuit - reinforcing a trope where male intensity equals romantic legitimacy. Kareena Kapoor Khan and Shahid Kapoor’s 2007

Jab We Met falls somewhere in between. Geet’s journey becomes defined by her impact on Aditya’s emotional revival. While the romance is balanced and beloved, the narrative momentum often leans towards the man more than the woman.

New Voices and Roads Beyond Male Gaze

The requisite for a genuine shift is female perspectives – stories told through women’s eyes, desires, vulnerabilities and agency.

Films like Queen and Lipstick Under My Burkha give narrative space to women’s emotional worlds. Films like Darlings portray women’s sexual and emotional desires without moral judgment, while a

Gangubai champions male characters who learn from female strength or share emotional labour.

Remaining Challenges

The problem is that mainstream

Bollywood still caters to mass audiences that often expect familiar tropes that includes male heroism and romantic conquest. And as a result even if women are made central characters, the emotional weight and

narrative urgency sometimes still favour male arcs.

Has the Male Gaze Evolved?

Yes, but partially. Perhaps it is mostly uneven, and incomplete.

Bollywood has started questioning and complicating its traditional gaze, and films with women becoming the narrative arc are no longer fringe; they have critical acclaim and box-office impact. But structural patterns persist. Many mainstream love stories still celebrate the man and depict women primarily in relation to him.

True evolution means love stories where women’s desires and vulnerabilities are not incidental and emotional journeys aren’t measured by whom a woman ends up with. And perhaps Bollywood is moving in that direction, propelled by an urban audience whose hunger for stories that reflect contemporary realities are on the increase. Yet the journey is ongoing, and

for every Queen, Metro…In Dino or Lipstick Under My Burkha, there are films that revert to older patterns.The question now is not whether Bollywood shows love differently, but rather whether the audience is ready to watch and value stories where love is mutual, complex, and truly shared.

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177089853476914935.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177071311265874579.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177089866690032944.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177087761287071162.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177089871495294861.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177077603394625504.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177081102966228140.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177074805788931893.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177063953658055705.webp)