For years, Bollywood has taught us that love arrives like a festival, a grand declaration of feelings that is loud, dazzling and impossible to ignore. It is what bursts into songs in mustard fields, defies disapproving parents and promises eternity. Romance, in Bollywood has always been a spectacle, has always been pursuit, has always celebrated youth. But what happens after the fireworks fade and the embers are all that remain? What happens when love is no longer breathless but is bruised, turned haggard by years of experience? What happens when love carries the weight of marriage, memory, children, ageing bodies, betrayal, and unfinished sentences? What happens when love evolves from pauses to silences? For the longest time, Hindi cinema had

little patience for those questions. Romance was always about falling in love, not staying in it, or surviving it. But long after you spell and fall in love, the stories continue – as they say – Picture abhi baaki hai mere dost.

Scattered across decades, and increasingly in contemporary years,

Bollywood has been learning to love grown-ups – not as side characters, chorus or comic relief. But rather as people whose emotional lives are as urgent, complicated and cinematic as any 20-year-old’s first crush.

The shift – though more apparent now – did not begin yesterday. It was quietly seeded in films like Ijaazat.

Love and the Dignity of Letting Go

Gulzar’s 1987 classic

Ijaazat is perhaps one of Hindi cinema’s most mature examinations of love. Two former spouses - Mahender and Sudha (Naseeruddin Shah and Rekha) run into each other at a railway station - a setting that Bollywood often uses as a romances signal for dramatic reunions. But here there are no

romantic crescendos, but only pauses and unfinished conversations. The two do not rediscover passion, but rather perspective. The film is an haunting exploration of how adult love is often less about reclaiming each other and more about accepting who we were and when we failed each other. What makes Ijaazat so compelling is that in a cinematic culture that equated true love with permanence, the film dared to suggest something radical -

sometimes love ends, and that ending can still be tender. Romance has many masks.

Loneliness in a Crowded City and The Lunchbox

If the 1987 classic

Ijaazat was ahead of its time, the 2013 Ritesh Batra film

The Lunchbox, with Irrfan Khan and Nimrat Kaur in lead roles brought mature longing into the multiplex era with a surprising subtlety. A mistaken tiffin delivery connects Ila, trapped in a loveless marriage, and Saajan, a widower drifting toward retirement. The poignancy of the film lay in how their love story unfolded through letters - confessions about disappointment, invisibility, routine. There was no dramatic chase or rebellion, it was just two adults recognising themselves in each other’s solitude.

The Lunchbox beautifully highlighted something that youthful romances often ignore.

Sometimes love is less about excitement and more about being seen. The film’s restraint - and its famously open ending - mirrored the uncertainty of adult life. Not every connection culminates in a grand gesture, sometimes possibility itself is transformative. Similarly Gulshan Devaiah and Saiyami Kher's

8AM Metro too is a beautiful romance of two strangers who meet on a Hyderabad metro train and strike up an unlikely friendship, helping each other through personal traumas. Manav Kaul and Shefali Shah's critically acclaimed short

Ankahi - a part of the 2021

Netflix anthology movie

Ajeeb Daastaans too focused on a love matured by experience as it followed a strained marriage, where Shah's character found emotional connection with a deaf-and-mute photographer (Manav Kaul). However, much like aged-wine and love, at its heart,

Ankahi is not about grand declarations, rather it is about what remains unsaid.

Desire Beyond Youth in Cheeni Kum

Even as Bollywood continues to celebrate older heroes serenading younger heroines, it has rarely examined older desire with nuance. R Balki’s 2007

Cheeni Kum disrupted that pattern by focusing on a sharp, witty romance between a 64-year-old chef andf a 34-year-old woman. The film was an excellent exploration on companionship where the two leads spar intellectually, challenging each other. Their intimacy is built on conversation, not conquest. R Balki excelled in this outing by exposing how age becomes scandalous only when love refuses to conform to societal expectations of what is “acceptable”.

Cheeni Kum treated older attraction not as a punchline, but as legitimate.

Badhaai Ho In Marriage After The Wedding?

While Hindi cinema has always adored weddings, with

Hum Aapke Hain Koun turning an entire wedding album into successful box office outing, what it has often neglected to do is what follows. Through the 2018 Amit Ravindernath Sharma film

Badhaai Ho, the script was cleverly flipped. While on the surface,

Badhaai Ho is a comedy about a middle-aged couple expecting an unexpected child, but beneath the humour lies a quiet celebration of long-married intimacy. Jeetendra (Gajraj Rao) and Priyamvada (Neena Gupta) are not embarrassed by their relationship, but rather by their children’s discomfort with it.

The film exposes the cultural hypocrisy of being comfortable watching young lovers on screen, but remaining unsettled by the idea that parents can remain sexually active.

Love Interrupted and Love Remembered

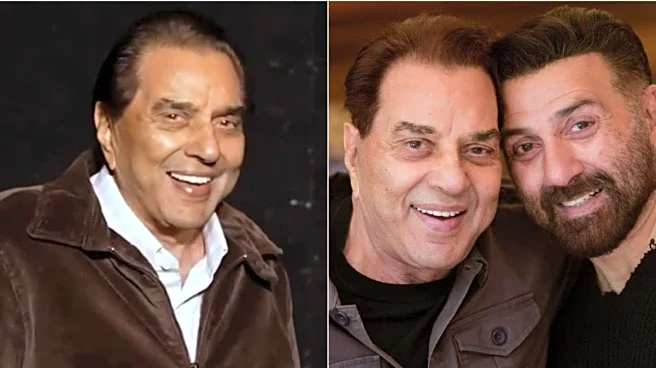

In Alia Bhatt and Ranveer Singh’s

Rocky Aur Rani Kii Prem Kahaani, even as the titular couple’s flamboyant romance dominates the narrative, the film’s most emotionally resonant thread belongs to Jamini and Kanwal (Shabana Azmi and the late Dharmendra) lovers separated decades ago by patriarchal rigidity. Their reunion is tender, hesitant and charged with everything they were denied – to the tunes of the immortal Abhi Na Jao Chod Kar. And by foregrounding elderly desire without mockery,

the film reiterates that love does not wither simply because society demands it, it endures despite everything.

Memory, Regret and Second Chances as well as Modern Intimacy

Then there are films like the 2022

Three of Us, which handled adult emotion with extreme delicacy. When Shefali Shah’s Shailaja, diagnosed with early dementia, revisits her childhood town, she reconnects with a man she once loved. There are no melodramatic declarations, but rather long walks, conversations hanging between pauses and silences and shared memories that are tethering on the brink of oblivion.

Three of Us understands that mature love is often about reconciliation – less with a person and more with time itself.

Similarly, Anurag Basu’s 2025

Metro In Dino captures emotional adulthood in a contemporary urbanscape. The filmmaker, through multiple narratives, weaving in and out of each other’s timelines, the film examines infidelity, compatibility, therapy, and the evolving expectations of partnership.

Metro In Dino suggests that in adulthood, love is less about how many years you’ve lived and more about how honestly you engage with your own flaws.

Bollywood and Mature Love

When taken together, the films chart a subtle but significant evolution in Bollywood’s romantic grammar from spontaneity to stillness.

Newer narratives prioritise conversation over conquest, exploring love after divorce, within long marriages, interrupted by circumstance, and shadowed by regret. In these stories,

romance is sometimes unfinished, remembered more than relived and surviving in companionship rather than chemistry.

Urban loneliness is predominant, divorce carries less stigma and women articulate dissatisfaction more openly than before.

The audience is ageing – both physically and emotionally, and

Bollywood appears to be tentatively embracing emotional accountability. The fireworks have not disappeared, but Bollywood has now realised that after the fireworks, love does not vanish; it changes.Beyond the initial fireworks of love, romance becomes quieter, deeper, and more fragile – and its time Bollywood embraces it with more maturity.

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-17709720403932929.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177073762995729463.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177073402755726223.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177074817751365859.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177089853476914935.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177081102966228140.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177089871495294861.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177097225847491038.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177089866690032944.webp)