Love,

in its purest form, is rich, abundant with dreams, hopes, and gratitude. The innocence of young romance can’t be traded for any luxury in the world. Bursting with vibrant energy, passion and warm intimacy, its tenderness holds many desires – of a happy future, being assured to have a companion through thick and thin and building a small world where there’s unconditional joy and love. But when the small world grapples with breathing, the sense of innocence turns into fear. Stories rooted in different cultures have ingrained a variety of emotions and forms of love in cinema. When romance crosses the imaginary line of class, caste and religion, its beauty changes definition and the rose-tinted glass gets bloodstained.

Heart that beats for respect

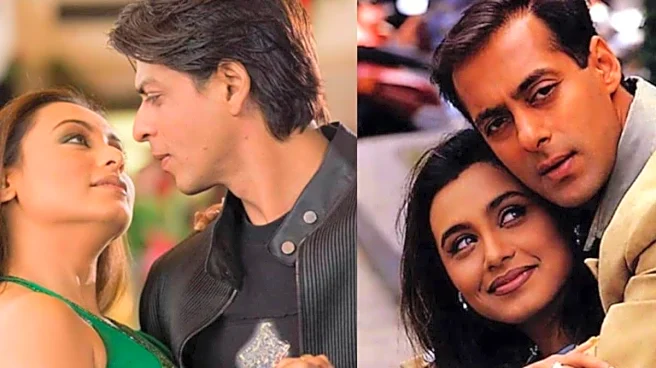

While Karan Johar’s Dharma Productions has shown the softer side of love with films like

Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, the darker reality is what Madhu (Ishaan Khatter) and Parthavi (Janhvi Kapoor) had to experience in

Dhadak. Unlike the Poos and Rohans of the world, where loving the person of their choice is cakewalk, companionship has a different meaning for our protagonists. When caste and class inequalities are heavier than the weight of innocence, it gets crushed.

Dhadak, an official remake of the Marathi

Sairat, showcases a tender love story between a lower-caste man and an upper-class woman. However, their realities are not enough for their families. Rebellion against society does not go unnoticed.

Horrors of honour killing in cinema

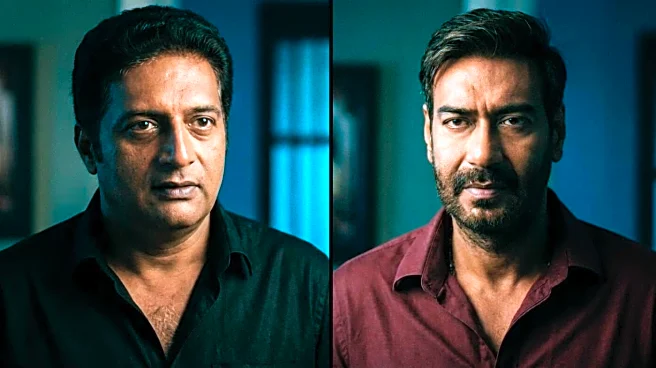

Though social perceptions have changed and awareness evolved, there’s always one anti-social element in the perfect story that makes living hell. Parthavi and Madhu’s unrequited love reminds us of how Ajay (Ajay Devgn), Raja (Aamir Khan), Kajal (Kajol) and Madhu (Juhi Chawla) fought against it in

Ishq. Instead of succumbing to parental pressures, they contested till the end and proved that love heals. While

Ishq had a more urban setting, rural areas, especially in Tier-2 and Tier-3 cities, it looks at love sans barriers as a sin. This perception that honour killing has gone extinct with better education and awareness was shattered when Meera (Anushka Sharma) took the NH10 route with her husband (Neil Bhoopalam) and returned home as a broken person. Family members, who sometimes double down as products of societal evils, do not think twice before taking strict action against lovers who have to survive for their love to find fruition. Battling a horrific situation, Meera in

NH10 loses her husband after a romantic night at a posh Noida eatery. She doesn’t blink an eye before extending a helping hand to save someone else’s life. In the end, worlds collapse, but

patriarchy wins.

Family rivalries and an immortal love story

If

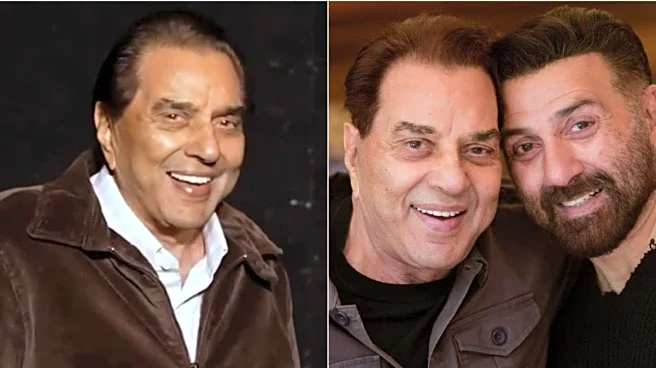

NH10 made the challenge of fighting patriarchy and horrors of honour killing relevant in contemporary society, it was Aamir Khan and Juhi Chawla's (1988)

Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak which made the tragic end of young love immortal. When the film was made, the audience sensibility was different, and so was their understanding of societal evils. Family rivalry might be a dated concept now, but in the ‘80s, it was a reality. In Raj and Rashmi’s sweet story, the villains are their feuding clans, who are determined not to let their relationship flourish. Even then, they don’t let go of each other. After Rashmi’s death at the hands of her father’s henchman, Raj commits suicide, making it an immortal relationship that transcends human evils.

Sacrifice can have different meanings. Raj and Rashmi showed their perspective in

Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak by making their pair immortal; Zoya (Parineeti Chopra) and Parma (Arjun Kapoor), the ultimate Ishaqzaade of modern India, followed them. Their case was trickier due to the politics of religion. A Hindu-Muslim intercaste marriage doesn’t still account for a perfect ending. Zoyas and Parmas outnumber Veer (Shah Rukh Khan) and Zaara (Preity Zinta) in smaller towns. Dancing to

Jhallah Wallah and

Chokra Jawan establish Zoya and Parma as rebel lovers. As they learn this world is too small and inadequate to accommodate and nurture their future, guns become their best friends and adjudicators. Such is also the case in the film

Anwar. Despite differences in religion, Mehru (Nauheed Cyrusi) and Udit (Hiten Tejwani), find comfort and companionship in each other. They reunite as lovers, but in realms where there are no conditions.

Dignity over warring families

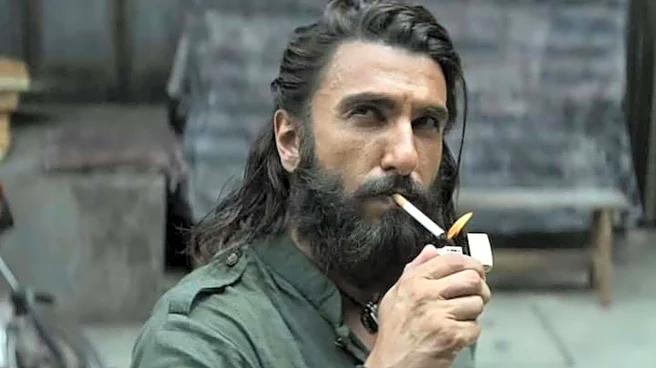

Immortal love in cinema has found a home in Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s grandeur, too. When Ram Rajadi (Ranveer Singh) and Leela Sanera (Deepika Padukone), in

Goliyon Ki Raas Leela - Ram Leela, are tired of contesting against a deaf world, they pull the trigger together and quietly end their suffering. The biggest antagonist in their story was caste. Set in rural Gujarat, the Rajadis vs Sanera communities were caught in an intense battle of

honour, reputation and pride. Ram and Leela chose their dignity. One of the shades of love is deep red, which symbolises pain, sacrifices, and blood. Urban stories might not decode their depth beyond the surface gloss, but the sins of falling in love rip away privileges and many times – humanity also. Call it ‘toxic’ or unimaginable, this side of survival has shattered countless lives. Subjects like communal differences, interfaith relationships and class-no-bar partnership are tougher than they appear. Especially in villages and towns that run on gender politics. Cinema is the reflection of society and sadly, these real horror tales have shaken the entire film industry that constantly brings heartland sagas to the global platform.

No

love story is perfect. Not every couple has a happily-ever-after. Movies don’t endorse tragic ends, but play a catalyst in educating the audience about the evils that exist even in the modern era.

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177089871495294861.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177081102966228140.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177077603394625504.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177086352380239409.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177063953658055705.webp)