Two nations, one voice, and the curious irony of a poet who hated boundaries yet defined them for half a billion people.

It’s January 24, 1950. In the high-ceilinged

Constitution Hall in Delhi, the air is thick; not just with the dust of a new republic, but with the weight of choice. Dr. Rajendra Prasad stands up. He doesn’t offer a vote. He offers a declaration. Jana Gana Mana, he announces, will be the song of the land.

No debate. No show of hands. Just a melody adopted into the spine of a nation.

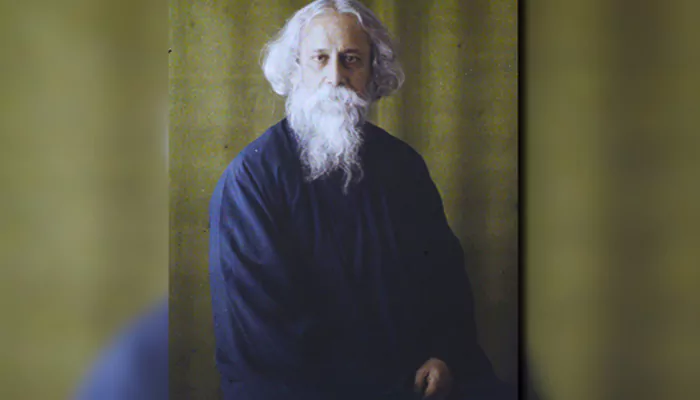

But if you zoom out -way out - the story gets stranger. Because the man who penned those lines, Rabindranath Tagore, had already been dead for nine years. And while he was busy crafting the sonic identity of India, he was accidentally writing the future anthem for a country that didn't even exist yet: Bangladesh.

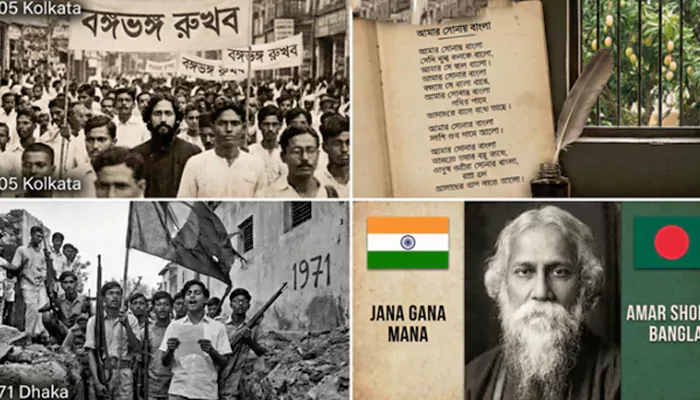

It is a feat of literary gymnastics that no other writer in human history has managed. Two sovereign nations. Two anthems. One author.

The Myth of the Sycophant

Let’s clear the air about Jana Gana Mana. You’ll hear the rumors at dinner parties; someone’s uncle always claims it was written to praise King George V. "Dispenser of India's destiny," they’ll quote, eyebrows raised. Rubbish.

Tagore was many things, but a bootlicker wasn't one of them. He wrote the song in 1911, yes, the same year the King visited. But when a friend asked him to write a eulogy for the monarch, Tagore - likely cranky and definitely insulted - penned a hymn to the "Eternal Charioteer" of human history instead. He basically told the King, "You aren't the boss; the divine spirit of India is.”

The fact that the British bureaucrats didn’t get the sarcasm? That’s on them.

The Song That Waited 66 Years

Now, pivot to 1905. Lord Curzon has just taken a knife to the map of Bengal, slicing it into East and West. The streets of Kolkata are on fire with protest. Tagore, caught in the fervor, writes Amar Sonar Bangla (My Golden Bengal).

It wasn’t a victory march. It was a love letter.

He talks about the scent of mango orchards in spring; the tenderness of the riverbanks. It’s intimate, almost dangerously so for a political song. For decades, it was just a folk tune, something grandmothers hummed. Then came 1971.

East Pakistan bled into Bangladesh. The students fighting in the trenches of Dhaka didn’t want a martial tune. They wanted a memory of what they were fighting for. They dusted off Tagore’s 66-year-old lyric, and suddenly, the same man who defined India’s "mind" was defining Bangladesh’s "heart."

The Irony of the Universalist

Here is the kicker, though. The man who gave two nations their most patriotic symbols actually loathed nationalism. He called it a "great menace". He thought borders were silly lines drawn by small men.

You have to laugh at the cosmic joke of it. A man who preached a world without walls ends up building the emotional foundations for two of South Asia’s biggest ones.

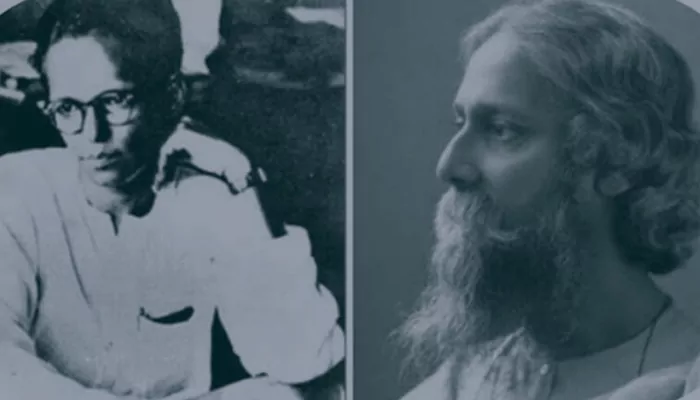

Ananda Samarakoon (left) was a student of Tagore at Viswa Bharati

It’s said that Ananda Samarakoon, the composer of Sri Lanka’s Sri Lanka Matha, was a student of Tagore’s at Visva-Bharati. Legend has it Tagore nudged the lyrics in a certain direction, or perhaps just the vibe. Whether he held the pen or just the inspiration, his fingerprints are all over the subcontinent’s throat.

So, when you stand up today - or any day - and hear those 52 seconds of Jana Gana Mana, remember the oddity of it. You aren't just singing for India. You are singing a verse from a poet who belonged to everyone, and therefore, to no one at all.History is funny like that; it rarely asks for permission.